We thought we understood the mosaic of identity-based interest groups that have come to define the Democratic Party’s base. We’ve come to assume that members of sexual, racial, and ethnic minorities naturally align with modern liberalism and the Democratic Party, and we seek special explanations when they don’t. We think we know what identity is, and what sense of community, what sense of politics, should flow from it—if only we could get people to think logically about their own interests.

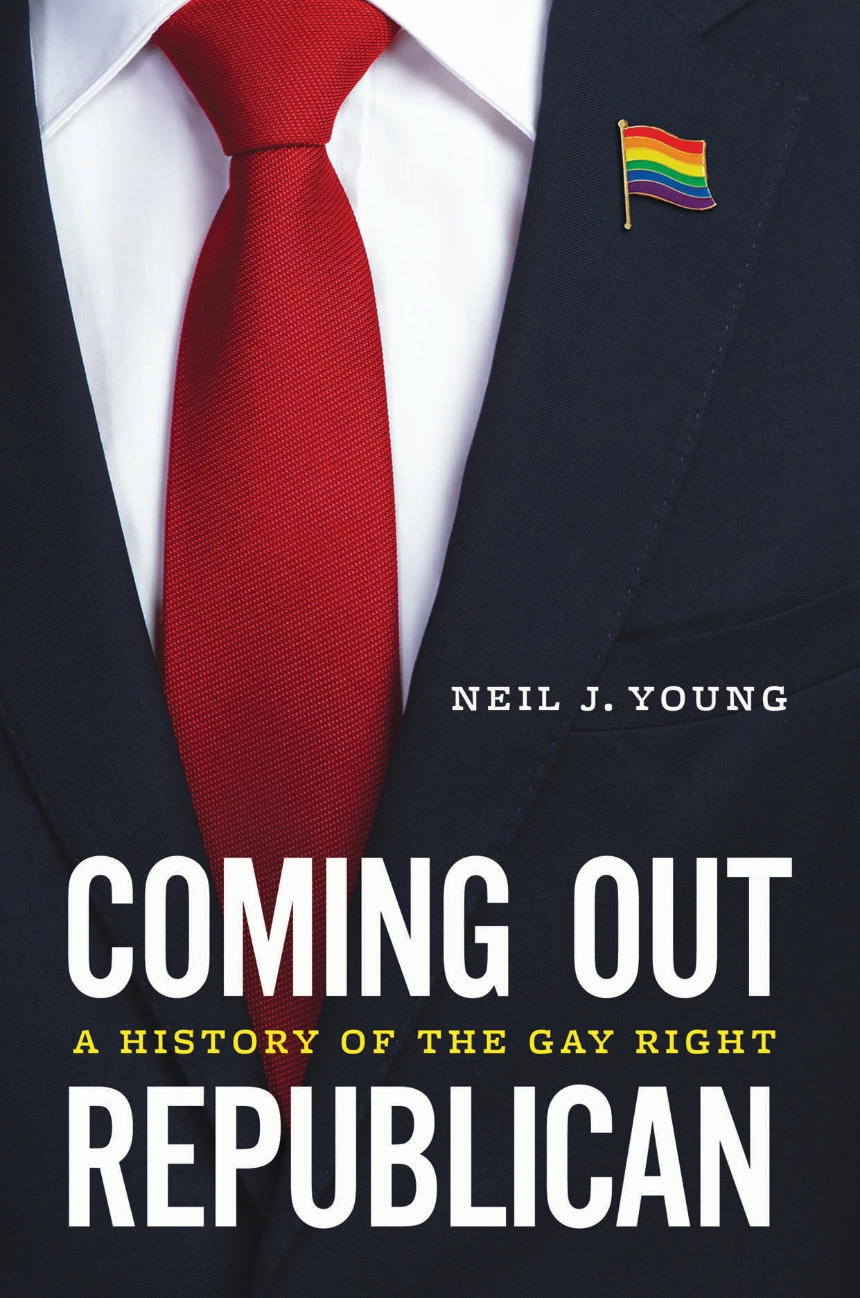

But in light of the recent defections among other groups once considered a stable part of the Democratic base, perhaps it’s time to question such assumptions. As Neil J. Young’s important new book, Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right, shows, the relationship between one’s identity and one’s interests or politics isn’t always predictable or straightforward. In nineteen brisk, engaging, historically sequenced chapters, Young lays out some of the ways that gay (mostly) men have aligned not with Democratic Party or progressive politics but with conservative and Republican Party activism over the past 75 years.

He populates this history with colorful and often sympathetic figures whose lives illustrate a variety of paths to conservatism. Some were born into conservative middle-class, military, Catholic, or Protestant families and kept to their parents’ conservative way of thinking. A few rebelled against liberal parents. Some zigzagged more than once between Left and Right. Some hewed close to the spirit of classical liberalism, with its view of privacy and individualism, others to the reactionary logics of classical conservatism: reflexive fealty to God and country.

Consider the story of Dorr Legg, one of the founders of the mid-twentieth century homophile movement. Legg was born in 1904 to a prosperous, small-property-owning family in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Police harassment and an arrest for “gross indecency” in the late 1940s eventually drove him out of the state, and he headed west—to California, of course, where he worked as a landscape architect. Los Angeles had its own pervasive patterns of police surveillance and harassment, but the scale of the expanding city at least provided opportunities for making connections. There, he and his partner, Merton Bird, a black accountant, formed a support group for interracial gay couples. After going to Mattachine Society meetings for a few years, Legg helped found ONE, Inc. in 1952, which Young describes as a more conservative alternative to the left-influenced Mattachines. Shortly after ONE’s founding, Legg launched, edited, and wrote for the organization’s journal, One Magazine.