Savannah is haunted. That’s the first thing tourists learn about this city at the northern end of Georgia’s hundred-mile coast—a notion solidified in the popular imagination by the success of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, both the 1994 book by John Berendt and the subsequent film directed by Clint Eastwood. Midnight revolves around a nouveau riche antiques dealer named Jim Williams. Berendt, formerly the editor of New York magazine, happened to be in Savannah in the early 1980s when Williams killed a roughneck rent boy; he chronicled the event’s reverberations through Savannah society, which he depicts as eccentric and decadent. “The whole of Savannah is an oasis,” an informant tells him. “We are isolated. Gloriously isolated!”

“I suspected that in Savannah I had stumbled on a rare vestige of the Old South,” Berendt concludes. This vestige isn’t exactly the plantation fantasy—for Berendt, the Old South seems to have something to do with an enduring, atavistic faith in certain habits and creeds. The white elite believe in social custom; they have their teas and luncheons. Williams, bred in small-town Georgia, is able to insinuate himself into this echelon, but he maintains connections to other worlds, too. Williams buttresses his defense with an extralegal approach: he engages the services of a black root worker named Minerva. (Related to hoodoo, root work is a West African–derived form of folk medicine or magic practiced in the South.) Williams explains to Berendt that Minerva had been the “common-law wife of Dr. Buzzard,” a famous voodoo practitioner. One of Dr. Buzzard’s specialties was in the legal realm, where he “was especially effective ‘defending’ clients in criminal cases. He’d sit in the courtroom and glare at hostile witnesses as he chewed the root.” After Dr. Buzzard died, Minerva continued his work both in and out of the courtroom. A central scene in the book is set in a cemetery: the midnight garden of the book’s title, where Minerva has Williams drop “nine shiny dimes” into the dirt while she communicates with his victim, whom she tries to persuade to “ease off a little.”

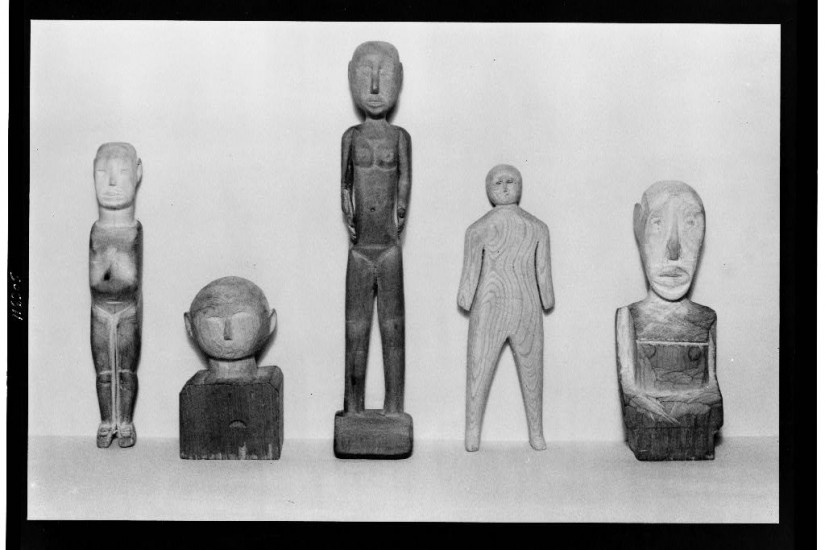

In some ways it was a familiar scene, and the notion of the southeast coast’s being “gloriously isolated” was not a novel proposition. Earlier in the century, a similar spirit undergirded another spooky book, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, a peculiar volume compiled in the 1930s by workers affiliated with the Federal Writers’ Project’s Savannah Unit. Other FWP workers in the South gathered oral histories of slavery; the Savannah Unit, under the leadership of a white woman named Mary Granger, embarked on a stranger and far more fraught mission. Inspired by the anthropologist Melville Herskovits, Granger believed the lack of outside influence had led black people to retain certain “African” cultural traits or “survivals.” Her idea of what these attributes were is expressed in the book’s title and in her introduction, which mentions “sorcery,” “root doctors,” “miracles and cures,” and “mystic rites.” One such rite would be familiar to Berendt’s readers: “Not very long ago when a man was arrested for murder,” Granger wrote, “his friends, wishing to save him, went to the grave of the murdered man, secured some dirt, and left three pennies on the grave.”