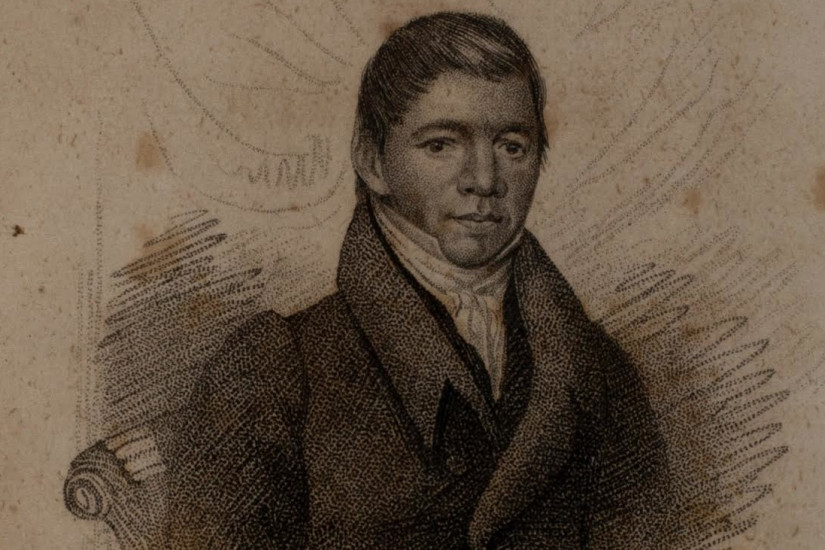

On April 1, 1839, a New York City medical examiner performed an autopsy on a man at a boardinghouse in a working-class neighborhood of lower Manhattan. He had performed scores of such examinations each month, but this one was especially significant though he did not recognize the person: 41-year-old William Apess had written more than any Native American writer before the 20th century, and had attained fame and notoriety in his short life for championing native peoples’ rights.

Still largely forgotten except by those who work in Native American studies, Apess deserves the same widespread recognition as others in the antebellum period who questioned the sincerity of the nation’s commitment to democracy. He was a leading light in a generation of reformers that included Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, champions of women’s rights; Frances Wright and Orestes Brownson, fighters for the dignity of labor; and William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, David Walker, and Frederick Douglass, advocates for African-American freedom and equality: voices unafraid to speak the truth about the emperor’s new clothes. In the 1820s and 1830s, Apess stood both with these critics yet, as a Native American, apart from them, his voice raised in protest against the plight of indigenous peoples, whom all too many white Americans wanted to believe were doomed to extinction.

No one could have predicted Apess’ meteoric rise. He was born in abject poverty in 1798 in rural Massachusetts, of “colored”—which at that time could mean mixed-race—parents who moved to Connecticut a few years later only to separate. He then lived with his grandmother but found little stability. She beat Apess so severely that the town’s overseers of the poor stepped in to place him with various white families before formally binding him out as an indentured servant.

His life changed, however, when he experienced a powerful conversion to Christianity as a result of Methodist preaching. Assuming control of his life for the first time, he escaped his indenture during the War of 1812 and enlisted among New York troops. Still only a teenager, he saw action in several battles around Lake Champlain and in expeditions against Quebec. At the end of the war, Apess spent time among Native American tribes in northern New York and eastern Ontario. When he returned to Connecticut months later, he formalized his commitment to Methodism through baptism and began to work as a preacher, often among mixed-race congregations.

In 1825, the Methodist leadership assigned Apess to a circuit throughout New England and New York. More and more confident in his self-expression, four years later he published A Son of the Forest, a spiritual autobiography that related the story of his life to date. He also preached and lectured in Boston, and came to the attention of prominent reformers like the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Apess also continued to publish, in 1833 both a sermon and the book Experiences of the Five Christian Indians; or, A Looking Glass for the White Man, in which he condemned the prejudice victimizing Native Americans.