In the one hundred-twenty years since the Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902, a number of intellectual giants have offered thought-provoking interpretations of this remarkable moment. Because the dominant players were housewives and not formally employed in factories, histories of the Jewish labor movement have largely glossed over the event. But in 1977, Herbert Gutman, the pioneering social historian who helped introduce “history from the below” into studies of the American working class, invoked the violence of May 1902 in a New York Times op-ed following the harsh censure of looters in the aftermath of that year’s power outage and blackout. Hyman, a trailblazing scholar of Jewish women’s history, broke new ground three years later with her landmark article, “Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York City Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902,” an essay that adeptly incorporated Gutman’s tools of social analysis. The uprising of Jewish housewives has likewise attracted the scholarly attention of some of the leading historians of American Jewish history, particularly of American Jewish women, who have correctly identified the kosher meats riots as a historical episode that upends conventional understandings of how gender, capitalism, and power operated among American Jews during the era of mass migration to the US.[2]

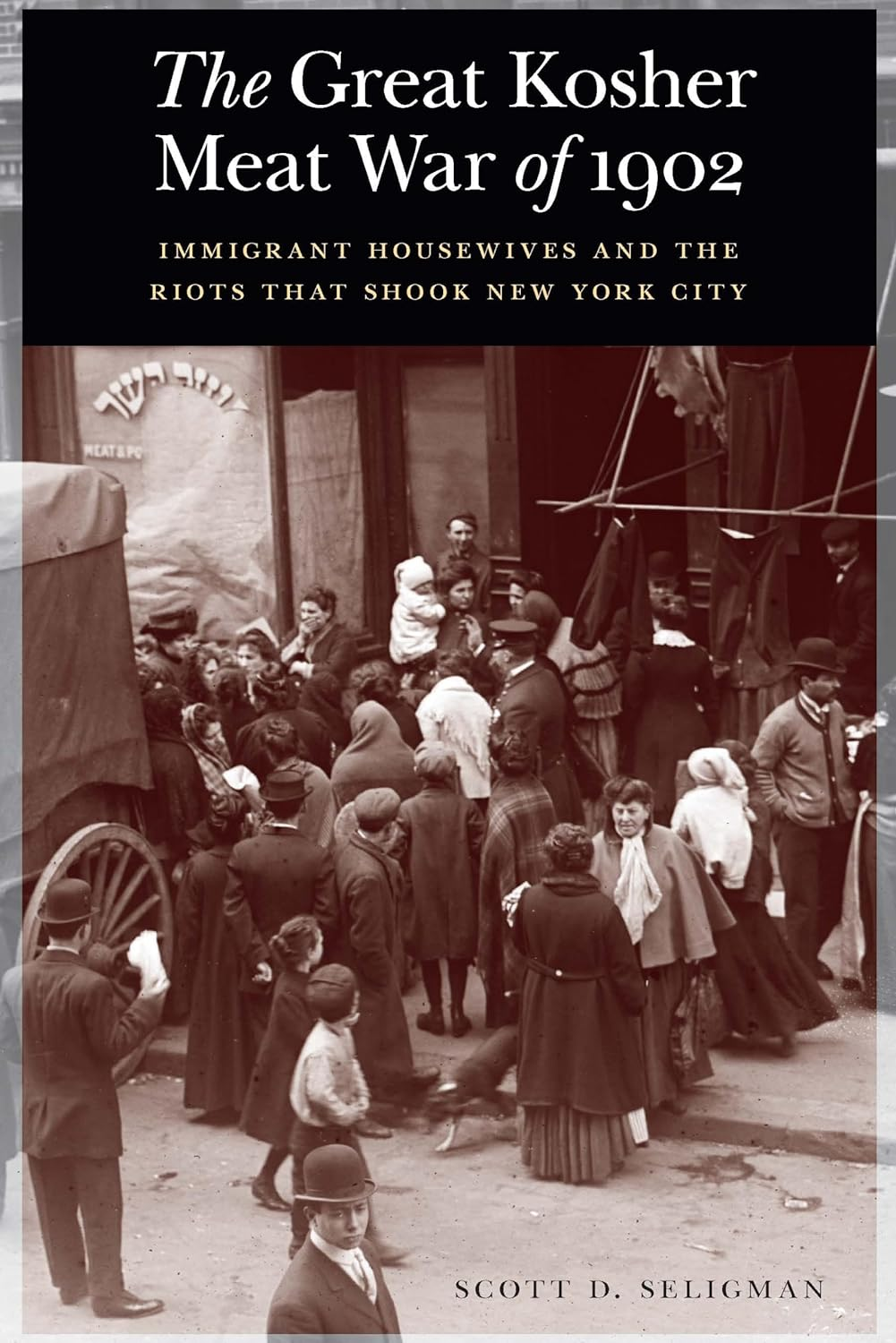

With The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902, Scott D. Seligman offers the first book-length treatment of the campaign of Jewish housewives against the “Beef Trust.” For readers familiar with Seligman’s prior works on Chinese American history, the narrative arc of The Great Kosher Meat War of 1902 will feel familiar. Seligman provides a highly readable chronology of the events between May and June of 1902 that, at the time, earned the title of “a modern Jewish Boston Tea Party” and, later, the Kosher Meat Boycott. He succeeds in bringing to life the largely forgotten and primarily female leaders of the consumer campaign, their roles within the collective effort to bring down the price of kosher beef, the internal divisions that developed, and their significance for American Jews. Largely constructed from media portrayals in both the English and Yiddish press (which covered the event feverishly), Seligman uncovers new details about the kosher meat riots that complicate older ideas about American Jewish women. Seligman gives readers a clear and comprehensive account of how the boycott, which he terms a “war,” arose, unfolded and declined, but also lived on in future political campaigns.