This is a tough year for the Georgia peach. In February, growers fretted about warm winter temperatures, which prevented some fruit from developing properly. They were more discouraged in March after a late freeze damaged many of the remaining fruit. By May they were predicting an 80 percent crop loss. Now in July they are lamenting one of the worst years in living memory.

With relatively few Georgia peaches this season, we might wonder where we would be without any Georgia peaches at all. One response to that question, surprisingly, is a shrug.

Georgia peaches account for only 0.38 percent of the state’s agricultural economy, and the state produces only between 3 and 5 percent of the national peach crop. Another region would make up the loss in production if demand were sufficient. A peach is a peach. Who cares about Georgia peaches?

But the Georgia peach’s imperiled future is not a simple matter of costs and profits. As a crop and a cultural icon, Georgia peaches are a product of history. And as I have documented, its story tells us much about agriculture, the environment, politics and labor in the American South.

Easy to grow, hard to protect

Peaches (Prunus persica) were introduced to North America by Spanish monks around St. Augustine, Florida in the mid-1500s. By 1607 they were widespread around Jamestown, Virginia. The trees grow readily from seed, and peach pits are easy to preserve and transport.

Observing that peaches in the Carolinas germinated easily and fruited heavily, English explorer and naturalist John Lawson wrote in 1700 that “they make our Land a Wilderness of Peach-Trees.” Even today feral Prunus persica is surprisingly common, appearing along roadsides and fence rows, in suburban backyards and old fields throughout the Southeast and beyond.

Yet for such a hardy fruit, the commercial crop can seem remarkably fragile. This year’s 80 percent loss is unusual, but public concern about the crop is an annual ritual. It begins in February and March, when the trees start blooming and are at significant risk if temperatures drop below freezing. Larger orchards heat trees with smudge pots or use helicopters and wind machines to stir up the air on particularly frigid nights.

The southern environment can seem unfriendly to the fruit in other ways, too. In the 1890s many smaller growers struggled to afford expensive and elaborate controls to combat pests such as San Jose scale and plum curculio. In the early 1900s large quantities of fruit were condemned and discarded when market inspectors found entire car lots infected with brown rot, a fungal disease that can devastate stone fruit crops. In the 1960s the commercial peach industry in Georgia and South Carolina nearly ground to a halt due to a syndrome known as peach tree short life, which caused trees to suddenly wither and die in their first year or two of bearing fruit.

In short, growing Prunus persica is easy. But producing large, unblemished fruit that can be shipped thousands of miles away, and doing so reliably, year after year, demands an intimate environmental knowledge that has developed slowly over the last century and a half of commercial peach production.

From windfall to icon

Up through the mid-19th century, peaches were primarily a kind of feral resource for southern farmers. A few distilled the fruit into brandy; many ran their half-wild hogs in the orchards to forage on fallen fruit. Some slave owners used the peach harvest as a kind of festival for their chattel, and runaways provisioned their secret journeys in untended orchards.

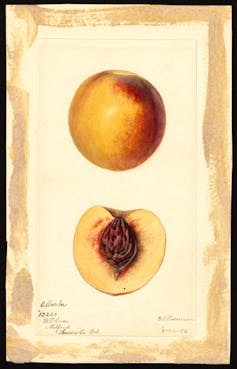

In the 1850s, in a determined effort to create a fruit industry for the Southeast, horticulturists began a selective breeding campaign for peaches and other fruits, including wine grapes, pears, apples and gooseberries. Its most famous yield was the Elberta peach. Introduced by Samuel Henry Rumph in the 1870s, the Elberta became one of the most successful fruit varieties of all time. Other fruits flourished for brief periods, but southern peaches boomed: the number of trees increased more than fivefold between 1889 and 1924.

Increasingly, growers and boosters near the heart of the industry in Fort Valley, Georgia sought to tell “the story” of the Georgia peach. They did so in peach blossom festivals from 1922 to 1926 – annual events that dramatized the prosperity of the peach belt. Each festival featured a parade of floats, speeches by governors and members of Congress, a massive barbecue and an elaborate pageant directed by a professional dramatist and sometimes involving up to one-fourth of the town’s population.

Festival-goers came from all across the United States, with attendance reportedly reaching 20,000 or more – a remarkable feat for a town of roughly 4,000 people. In 1924 the queen of the festival wore a US$32,000, pearl-encrusted gown belonging to silent film star Mary Pickford. In 1925, as documented by National Geographic, the pageant included a live camel.

The pageants varied from year to year, but in general told a story of the peach, personified as a young maiden and searching the world for a husband and a home: from China, to Persia, to Spain, to Mexico, and finally to Georgia, her true and eternal home. The peach, these productions insisted, belonged to Georgia. More specifically, it belonged to Fort Valley, which was in the midst of a campaign to be designated as the seat of a new, progressive “Peach County.”

That campaign was surprisingly bitter, but Fort Valley got its county – the 161st and last county in Georgia – and, through the festivals, helped to consolidate the iconography of the Georgia peach. The story they told of Georgia as the “natural” home of the peach was as enduring as it was inaccurate. It obscured the importance of horticulturists’ environmental knowledge in creating the industry, and the political connections and manual labor that kept it afloat.

Politics and work

As the 20th century wore on, it became increasingly hard for peach growers to ignore politics and labor. This was particularly clear in the 1950s and ‘60’s, when growers successfully lobbied for a new peach laboratory in Byron, Georgia to help combat peach tree short life. Their chief ally was U.S. Senator Richard B. Russell Jr., one of the most powerful members of Congress in the 20th century and, at the time, chair of the Subcommittee on Agricultural Appropriations. The growers claimed that an expansion of federal research would shore up the peach industry; provide new crops for the South (jujube, pomegranate and persimmons, to name a few); and provide jobs for black southerners who would, the growers maintained, otherwise join the “already crowded offices of our welfare agencies.”

Russell pushed the proposal through the Senate, and – after what he later described as the most difficult negotiations of his 30-year career – through the House as well. In time, the laboratory would play a crucial role in supplying new varieties necessary to maintain the peach industry in the South.

At the same time, Russell was also engaged in a passionate and futile defense of segregation against the African-American civil rights movement. African-Americans’ growing demand for equal rights, along with the massive postwar migration of rural southerners to urban areas, laid bare the southern peach industry’s dependence on a labor system that relied on systemic discrimination.

Peach labor has always been – and for the foreseeable future will remain – hand labor. Unlike cotton, which was almost entirely mechanized in the Southeast by the 1970s, peaches were too delicate and ripeness too difficult to judge for mechanization to be a viable option. As the rural working class left southern fields in waves, first in the 1910s and ‘20’s and again in the 1940s and '50’s, growers found it increasingly difficult to find cheap and readily available labor.

For a few decades they used dwindling local crews, supplemented by migrants and schoolchildren. In the 1990s they leveraged their political connections once more to move their undocumented Mexican workers onto the federal H-2A guest worker program.

Not so peachy

“Evr'ything is peaches down in Georgia,” a New York songwriting trio wrote in 1918, “paradise is waiting down there for you.” But of course everything was and is not peaches down in Georgia, either figuratively or literally.

Georgia itself doesn’t depend on the fruit. There may be plenty of peaches on Georgia license plates, but according to the University of Georgia’s 2014 Georgia Farm Gate Value Report, the state makes more money from pine straw, blueberries, deer hunting leases and cabbages. It has 1.38 million acres planted with cotton, compared to 11,816 acres of peach orchards. Georgia’s annual production of broiler chickens is worth more than 84 times the value of the typical peach crop.

Variable weather and environmental conditions make the Georgia peach possible. They also threaten its existence. But the Georgia peach also teaches us how important it is that we learn to tell fuller stories of the food we eat – stories that take into account not just rain patterns and nutritional content, but history, culture and political power.![]()

William Thomas Okie, Assistant Professor of History and History Education, Kennesaw State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.