Among the 80,000 images in the photo library of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—along with historical charts, whales and coral reefs, and many, many storm-tossed ships—is a picture that seems to beg for further explanation. Five smiling young women in matching short red wetsuits, sit on the edge of an orange pontoon in the bright tropical sun. The enigmatic caption: “In 1970, all female team performed as well as males in scientific sat mission.”

That, according to marine biologist Alina Szmant, who identifies herself as the second woman from the right (“the one with coquettish grin”), is a bit of an understatement—and only part of a story that was for her “an experience of a lifetime.” In fact, according to Szmant, the first all-female experiment in underwater living (“sat” refers to “saturation diving”) was an undiluted success.

“We performed admirably,” Szmant says, of the 14 days she and her colleagues spent living and working in a submerged laboratory known as Tektite more than fifty years ago. “We spent more hours in the water doing science than any of the male groups.”

Of course, Szmant and her fellow aquanauts never set out to prevail in a submarine battle of the sexes. They were there for the scientific opportunities—and for the adventure. And although the Tektite project may be little remembered today, its impact on research, exploration and the history of women in science has been quietly profound.

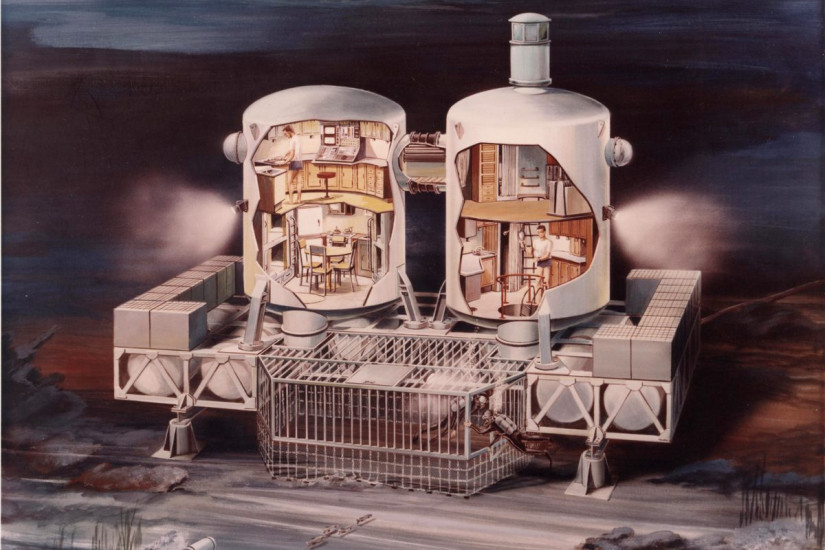

Szmant was a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography when she heard about an intriguing request for proposals put out by the U.S. Department of the Interior and NASA. They were looking for a team of scientists to spend two weeks in the Tektite underwater habitat, parked off the shore of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Named for a type of glassy pebble sometimes formed by meteorite impacts, Tektite consisted of two 18-foot-high metal cylinders connected at the base. Inside was a lab and storage space, a small kitchen with a Harvest Gold refrigerator and microwave, a tiny bathroom and no-frills bunks. Its original inhabitants, the year before, had been a team of male scientists whose primary research goal was to see whether they experienced any adverse effects from spending two months underwater.

“Man had walked on the moon, but NASA was thinking about longer missions,” Szmant explains. “They were interested in the medical and psychological side of things—what happens when people are isolated from society and have to live with only a few other people?”