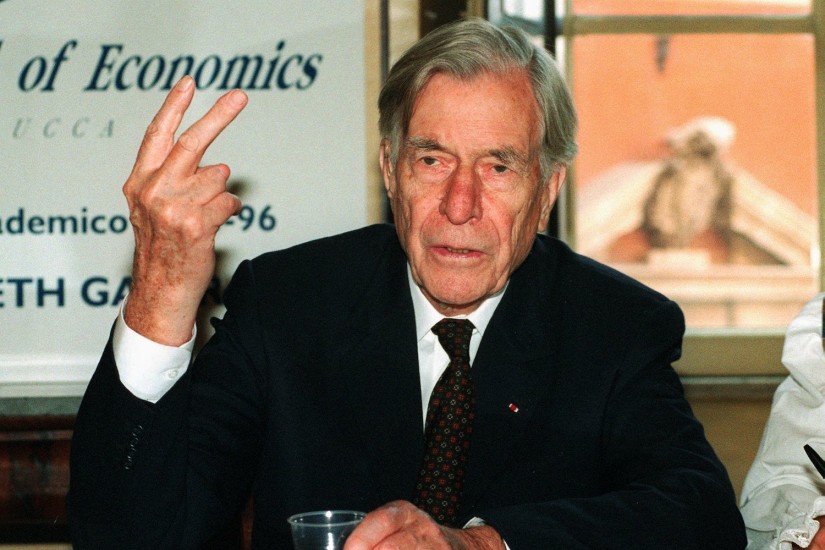

In his 1952 book American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power, the great 20th-century economist John Kenneth Galbraith wrote:

Increasingly, in our time, we may expect domestic political differences to turn on the question of supporting or not supporting countervailing power. Liberalism will be identified with the buttressing of weak bargaining positions in the economy; conservatism — and this may well be its proper function — will be identified with positions of original power.

Ah, “countervailing powers.” You rarely hear the term today, but it’s time to bring it back. It’s key to understanding the debate playing out in the Democratic primary. And it offers a clearer way of thinking about the endless balancing act of political reform.

Let’s start with the Democrats. For all the talk of our socialist moment, there’s relatively little socialism being proposed. The only industry anyone is contemplating nationalizing is the health insurance industry, and now that Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) has backed off that position, it’s only Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) left arguing for it.

Here’s the truth: What the Democrats — including Sanders — are discussing isn’t so much a socialist agenda as a countervailing powers agenda.

A bit of history is helpful. In American Capitalism, Galbraith was picking three fights simultaneously. As his biographer Richard Parker wrote, the book was a critique of conservatives “with their property-equals-freedom argument,” of economists who believed that “competition equaled efficiency,” and of liberals who believed that “economic concentration inevitably undermined democratic politics.”

Galbraith’s theory, put simply, was this: Capitalism inevitably leads to big corporations, and thus requires other big institutions powerful enough to counter them. This is true between corporations, as a big buyer, like Amazon, forces the consolidation of small sellers, so they can better negotiate prices. But it’s true across spheres too. Big corporations require big government, as the public demands regulation and redistribution, and big unions, as workers band together to build clout.

The problem with the conservative theory, Galbraith thought, was that it was obvious that freedom to contract was insufficient. The problem with the economists was their idealized models blinded them to the way power choked off competition. And of the liberals who loathed the anti-competitive effects of bigness, Galbraith argued that their “most plausible alternative to competition is full public ownership,” which few seriously proposed, either then or now.

Competition was, and is, important. Antitrust law can be used to dismantle the worst monopolists. But Galbraith believed that in an advanced capitalist economy, the inevitability of bigness needed to be recognized, even embraced. “People want large tasks performed,” he wrote, and “large tasks require large organizations. That’s the way it is.”