Part II

John Moon wasn’t the only one who didn’t know what a paramedic was. Most people in America didn’t. Today the role is clearly defined: A paramedic is certified to practice advanced emergency medical care outside a hospital setting. They’re the people who shock hearts back into beating, insert breathing tubes into tracheas, and deliver pharmaceuticals intravenously whenever and wherever a patient is in need. Until the mid-1960s, however, the field of emergency medical services, or EMS, didn’t formally exist. Training was minimal; there were no regulations to abide by.

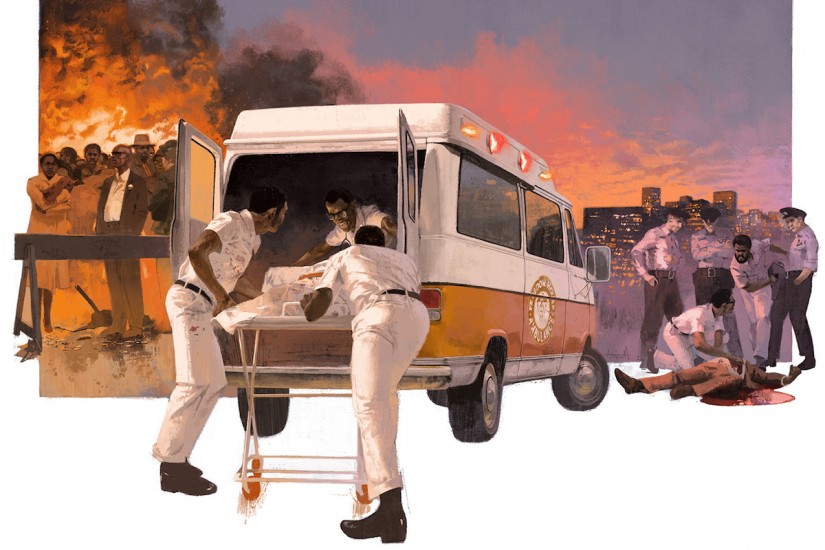

Emergency care was mostly a transportation industry, focused on getting patients to hospitals, and it was dominated by two groups: funeral homes and police departments. Call the local authorities for help and you’d likely get morticians in a hearse or cops in a paddy wagon. If you received any treatment en route to the hospital—and most likely you did not—it wouldn’t be very good. At best, one of the people helping may have taken a first-aid course. At worst, you’d ride alone in the back, hoping, if you were conscious, that you’d survive.

Standards for emergency care were so low that, in 1966, the federal government released a study reporting that a person was more likely to die from a highway accident in Kansas than from a gunshot wound in Vietnam. In a Southeast Asian rice paddy, a soldier could at least expect a medic to arrive and provide care where he’d fallen. An IV, bandages, pain meds—you could get them in the jungle, but not in an American city. Certainly not in a place like Pittsburgh, where the police ran the ambulance service and where calls to improve it, or to offer an alternative, had long been ignored. It took a very public death to open the door for change.

On the night of November 4, 1966, David Lawrence, a former mayor of Pittsburgh who’d also served as governor of Pennsylvania, collapsed on stage at a campaign rally. Someone called an ambulance and the police arrived. They put Lawrence onto a crude stretcher, loaded him into a paddy wagon, and drove ten minutes to Presbyterian-University Hospital, where he was met by Dr. Peter Safar, a wiry Austrian anesthesiologist. Lawrence had suffered a massive heart attack and showed no brain activity. His family ultimately decided to take him off life support.

Over the following weeks, as the city grieved, Dr. Safar stewed. The police had been poorly equipped. Safar concluded that, had they been driving an ambulance designed to enable crews to provide critical care, Lawrence might still be alive. CPR training could have helped, too. Safar would know. He’d all but invented it.