Richards was thrilled to be pursuing her research at MIT, but the university had a different perspective. In his biography of Richards, Ellen Swallow, Robert Clarke writes that Richards was an “experiment” that the school’s administrators were certain was going to fail. They accepted her in order to show that women weren’t cut out for higher learning, in order to maintain their all-male student body status. As one faculty meeting observer recorded: “she was put on trial for all women.” Richards was treated like a pariah and relegated to a solitary lab. Circumstances were daunting, but Richards made the space her own by carrying out her interest in chemistry, particularly as it applied to the home.

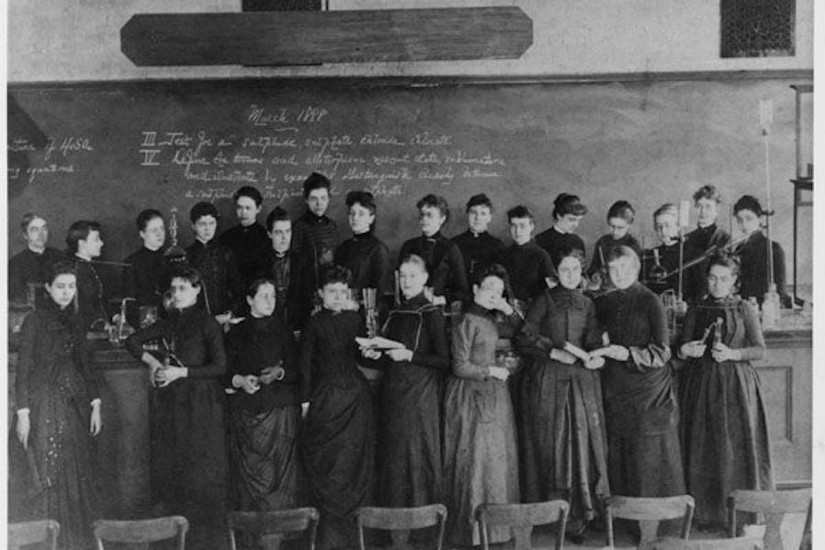

When Richards applied to MIT’s doctoral program in chemistry, they rejected her application outright, but she continued to expand her own branch of domestic chemistry. Richards lobbied the governing board of MIT to allow her to accept women students into her lab. With the help of the Women’s Education Association, she raised the $2,000 required to open the lab, and in 1876, Richards welcomed 23 women, mostly local teachers, to her Women’s Laboratory. MIT still considered them “special students.”

That same year, Richards introduced America to a new way of thinking about the interaction between nature and the built environment. While accompanying her husband on a research trip to Germany, she learned of Ernst Haeckel’s theory of oekology, or ecology. Richards, unlike Haeckel, viewed ecology through the lens of sociology; instead of seeing humans as acting on nature, she saw humans as interacting with nature. Historian Barbara Richardson notes an important difference between Richards’ understanding of ecology and the larger scientific community: ecology expanded beyond biological systems to include a complex system of relationships that encompassed the home, the economic and the industrial. When industry threatened to disrupt the ecological social balance with economic or environmental inequity, Richards believed that an educated population had the power introduce balance back into the system.