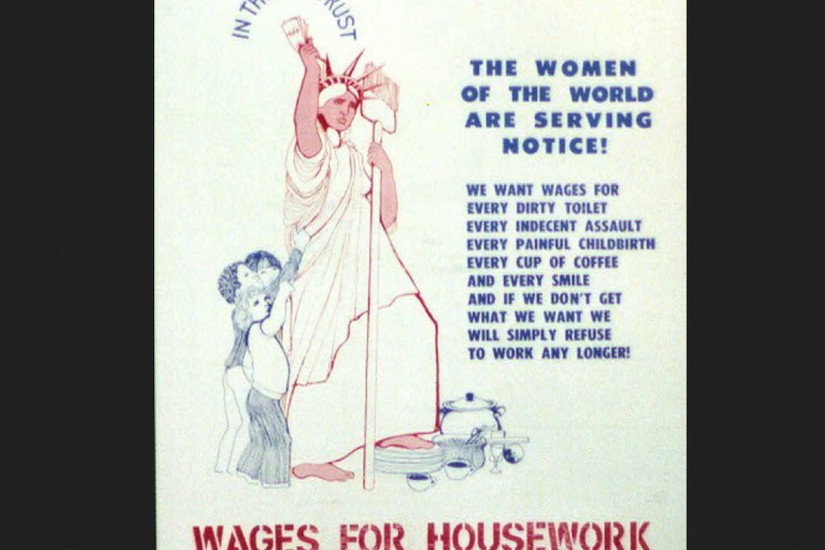

Wages for Housework helps to recover a movement that had modest origins but spread around the world within several years. From the gathering in Padua, Italy, that launched the international campaign in 1972 to the spin-off groups like the New York Committee, the women of Wages for Housework made arguments and demands that were well ahead of their time, helping to fill in the gaps overlooked by the mostly male left and the mostly liberal mainstream feminist movement, both of which have long excluded the home and the processes of social reproduction from their activism and thinking.

As the IFC’s launch statement (which served as a founding document for the New York Committee) put it:

We identify ourselves as Marxist feminists, and take this to mean a new definition of class, the old definition of which has limited the scope and effectiveness of the activity of both the traditional left and the new left. This new definition is based on the subordination of the wageless worker to the waged worker behind which is hidden the productivity, i.e., the exploitation, of the labor of women in the home and the cause of their more intense exploitation out of it. Such an analysis of class presupposes a new area of struggle, the subversion not only of the factory and office but of the community.

To demand wages was to acknowledge that housework—i.e., the unwaged labor done by women in the home—was work. But it was also a demand, as Federici and others repeatedly stressed, to end the essentialized notions of gender that underlay why women did housework in the first place, and thus amounted to nothing less than a way to subvert capitalism itself. By refusing this work, the Wages for Housework activists argued, women could help see to “the destruction of every class relation, with the end of bosses, with the end of the workers, of the home and of the factory and thus the end of male workers too.”