“Billion Dollar Babies” traces how Cabbage Patch hysteria accelerated the Black Friday retail thunderdome that would persist for decades and drew the blueprint for all holiday toy crazes to come (Furbies, Tickle Me Elmos, Hatchimals, et al.). But the lumpen, jolie-laide Cabbage Patch Kids, who descended from Appalachian folk-art communities, were unlikely avatars of this new era of grasping Reaganite consumerism. In 1982, Coleco Industries—the maker of hockey tables, aboveground swimming pools, and something called Electric Action Football—acquired the licensing rights to Little People, which were the popular soft-sculpture creations of Xavier Roberts, a craft-store manager in small-town Georgia and the founder of a company named Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. Under Coleco, the Little People were rebranded as Cabbage Patch Kids, but, even once they were being cranked out in droves from factory facilities in China, Roberts insisted on preserving trace elements of the homespun—supposedly, every single Kid represented a unique permutation of face shape, features, hair and skin type, and clothing. The conundrum, as a former Coleco executive explains in the documentary, was in how to manufacture “one-of-a-kind, mass-produced products.” The resulting shortages, which doubled as an accidental promotional stunt and fuelled the melees of 1983, prompted the Nassau County consumer-affairs commissioner to accuse Coleco of false advertising. (The company temporarily pulled its Cabbage Patch television ads.)

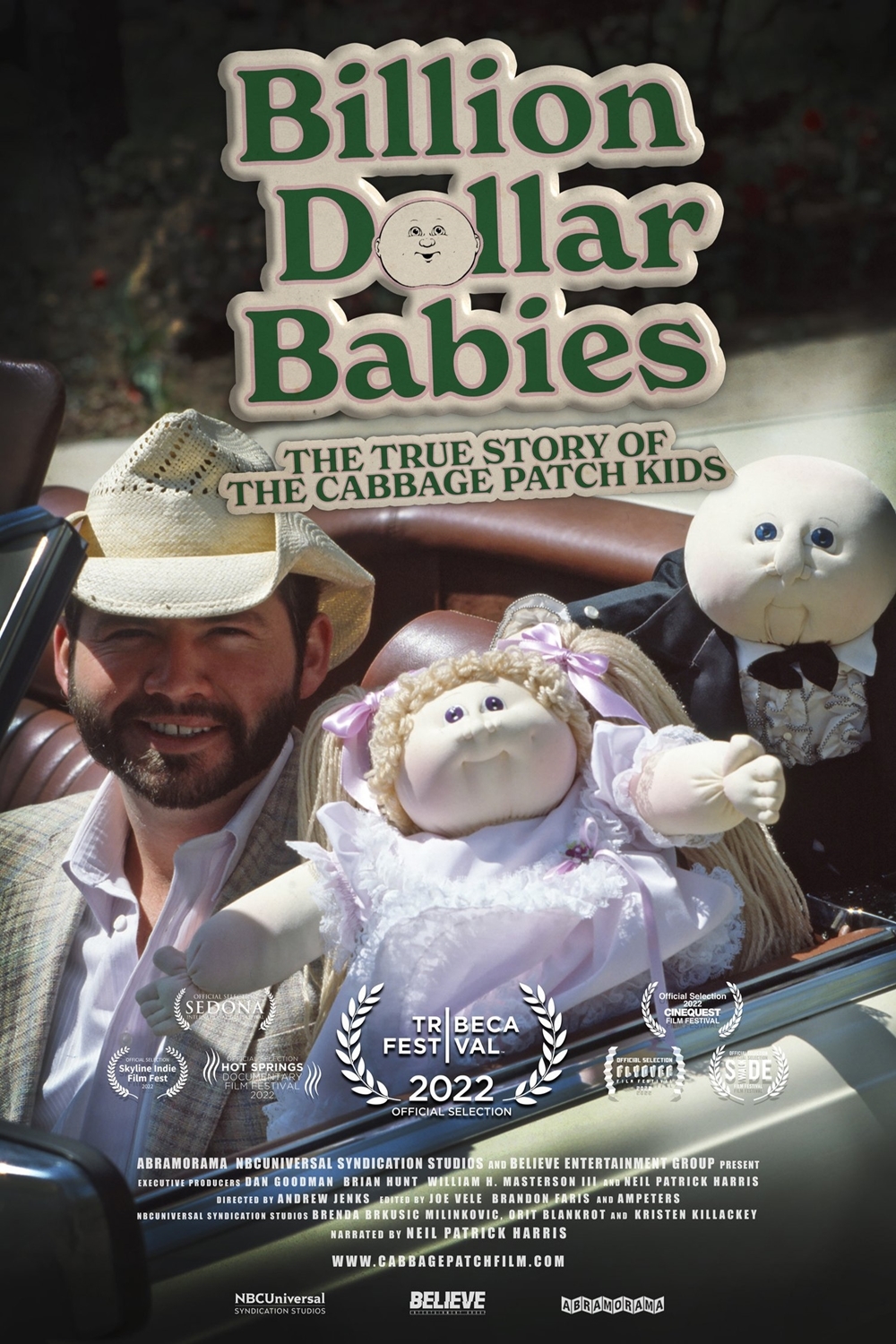

In his cowboy hat and boots, Roberts comes across in “Billion Dollar Babies,” at least at first, as a gee-whiz good ol’ boy, still happily flummoxed by his astronomical, near-accidental success. But it seems that the conception of a Cabbage Patch Kid required the contributions of both a mother and a father. More than a decade before Coleco signed its deal with Roberts, a Kentucky folk artist named Martha Nelson Thomas had begun making and selling Doll Babies—painstakingly handcrafted, uncannily Little People–ish creations. In 1976, Roberts met Thomas at a crafts fair and, for a time, offered to stock Doll Babies at his store; after she soured on the idea, Roberts wrote to her, “We will definitely [be] carrying your type of dolls, either made by you or by someone else.” The someone else turned out to be Roberts himself—and, unlike Thomas, he obtained a copyright. (Perhaps to underline this show of force, he also insured that his signature was on the tushies of the Cabbage Patch Kids.) “Art needs to be copyrighted,” Della Tolhurst, the longtime president of Original Appalachian Artworks, states in “Billion Dollar Babies.” Or, to paraphrase Mark Zuckerberg in “The Social Network,” if Martha Nelson Thomas were the inventor of Cabbage Patch Kids, she’d have invented Cabbage Patch Kids. (Roberts and Thomas litigated for years, and Thomas eventually received a settlement.)