In the wake of the 2015 Rachael Dolezal and 2020 Jessica Krug race scandals, in which these two white women deceitfully posed as Black women to advance their careers, “Who’s Black and why?” sounds like a quintessentially modern question. Likewise, the war of words among proponents of Black Lives Matter, All Lives Matter, Blue Lives Matter, Trans Lives Matter, and any number of other possible derivations—including the unarticulated but ubiquitously present White Lives Matter (most)—seems to be born of this millennium. Yet, as a new book coedited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Andrew S. Curran shows, these queries and concepts have a deep history that connects our current moment to a past centuries ago. This connection reveals the inhumane origins and the age-old racial politics of these hotly contested subjects.

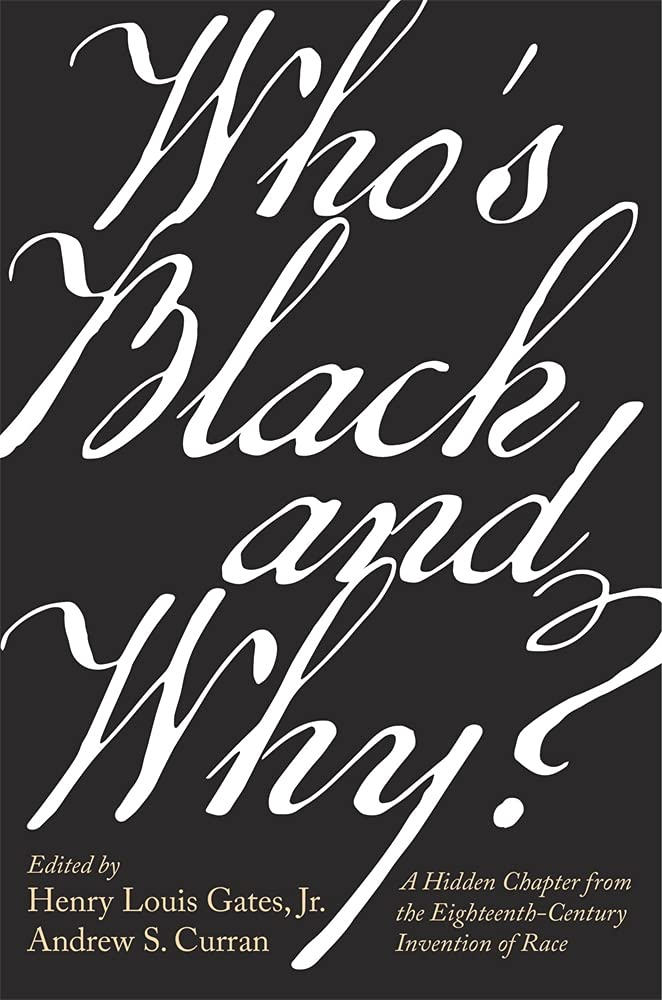

Who’s Black and Why?: A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race brings us back in time and across the Atlantic to the port city of Bordeaux in France, where a group of local would-be intellectuals were puzzling over racial difference: What separated their own tacitly normative whiteness from (what they viewed as) the anomaly of Blackness?

“What is the physical cause of the Negro’s color, the quality of [the Negro’s] hair, and the degeneration of both [Negro hair and skin]?” asked the Royal Academy of Science of Bordeaux in 1741. This question—a prompt employed by the academy as part of an essay contest—was followed three decades later, in 1772, by an even more heinous one: “What are the best ways of preserving Negroes from the diseases that afflict them during the crossing to the New World?”

To specialists in Atlantic slavery, it might come as little surprise that the Royal Academy of Science of Bordeaux held essay contests on two topics relating to the exploited peoples upon whose backs the tremendous wealth of the city and, more broadly, of European empires was erected. To the general public, in contrast, the prominence and centrality of pseudo-scientific debates about race taking place in one of France’s most venerated academies might appear a bit more shocking. In fact, the academy’s inquiries of 1741 and 1772 were “only the latest iteration of a two-thousand-year-old fascination with dark skin.” Nevertheless, argue Gates and Curran, the essay competitions represent a watershed in the history of ideas, science, and medicine: “Never before had the Bordeaux Academy, or any scientific academy for that matter, challenged Europe’s savants to explain the origins and, implicitly, the worth of a particular type of human being.”