The town of Downieville, California, situated at a fork of the Yuba River, about seventy-five miles northeast of Sacramento, began as one of the gold rush’s earliest mining camps. It quickly became a hub for miners in the region—a place where they could restock their provisions and find amusement away from the diggings. Gambling saloons, restaurants, hotels, and even a small theatre all occupied a single street, wedged between a steep mountain slope and the river. Like many parts of California during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Downieville area became home to a population of Chinese immigrants. As the number of Chinese people on the Pacific coast increased, so did white Americans’ loathing for the “heathen race.” The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882, banned the immigration of Chinese laborers, and dozens of communities across the western United States expelled their Chinese residents. Yet Downieville’s Chinese quarter persisted, in spite of the turbulence. In August, while researching a book I am writing about Chinese exclusion, I visited the California Historical Society in San Francisco and encountered for the first time a small red ledger, dating back to the turn of the twentieth century, that recorded the names and faces of Downieville’s Chinese residents. Accounts of the lives of Chinese people who experienced the cruelties of this era are rare, so I was immediately drawn to the volume, but I also found myself stricken as I began paging through it.

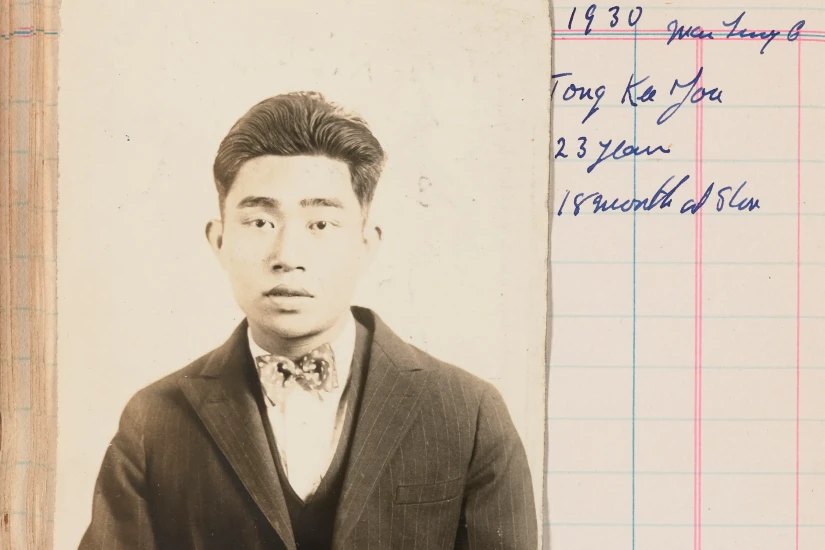

The ledger, which measures roughly eight inches long and five inches wide, belonged to John T. Mason, a constable in Downieville. The date on the first page is April 8, 1890, though some of the ledger’s notations seem to have been recorded earlier. Ephemera consume the first few pages: instructions for treating varicose veins, notes about a letter sent to a detective bureau in Cincinnati, a mailing address in Seattle for “Mrs. H. Libby,” a list of legal summonses served between 1889 and 1890. But the book’s real purpose starts to reveal itself on page 4, with a lengthy index of names and a note at the top that reads, “Chinese Photographed by DD Beatty at Downieville Feb 20th, 1894.” What follows is a collection of a hundred and seventy-six photographs of Chinese residents of Downieville and the surrounding area, pasted two to a page, accompanied by notations for each subject’s name, age, height, occupation, place of residence, and select physical characteristics: “little finger of right hand crooked,” “mole under right ear,” “pockmarked.”