How did countercultures commune before the Internet? One quaint and underappreciated precursor to the information highway was the underground press that proliferated during the late 1960s. The medium was never more the message. Sprouting in cities and college towns across America, these rambunctious weekly or biweekly tabloids flourished for a half dozen years, a form of what, referring to the spontaneous development of jazz, Ishmael Reed—a cofounder of a quintessential such paper, the Lower Manhattan–based East Village Other, a.k.a. EVO—called “Jes Grew.” Thanks in part to the Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), a national network whose members were allowed to reprint one another’s work, these self-identified rags spread like kudzu—to take the name of a triweekly published in Jackson, Mississippi.

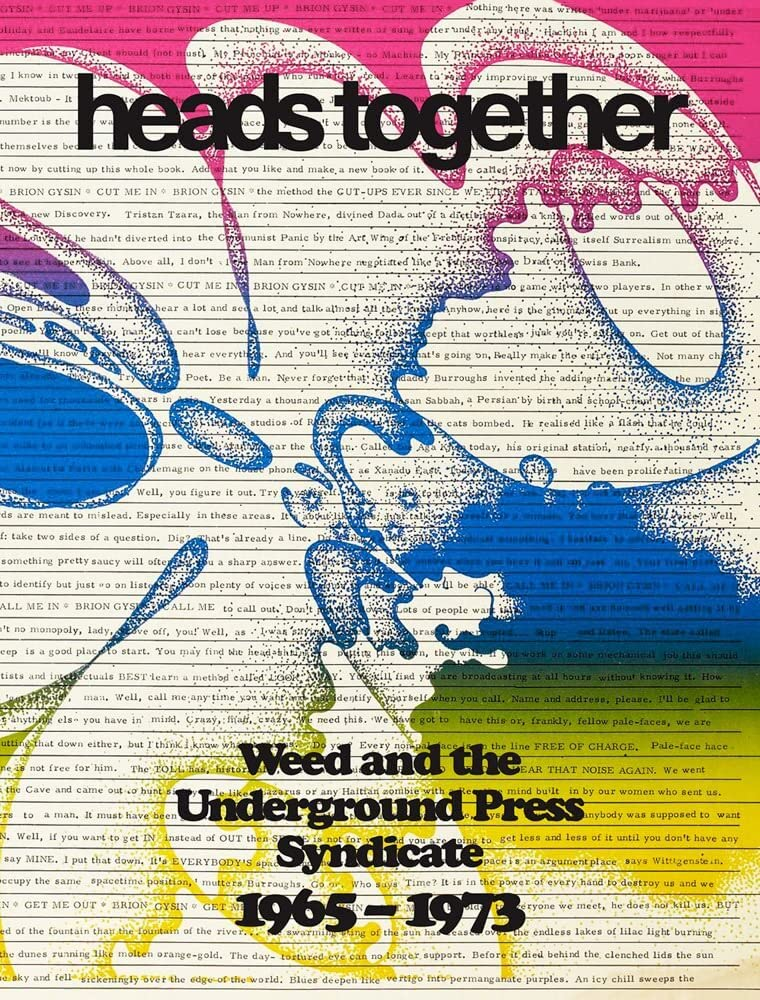

The vegetative metaphor was inevitable. According to Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965–1973, an artfully designed scrapbook curated by David Jacob Kramer, two entities propagated the underground. One was the UPS, which included five papers at its founding in 1966 and grew nearly fiftyfold over the next five years. The other was the popularity of marijuana. The UPS dissolved by degrees in the mid-1970s, whereas weed, fulfilling a fond dream of the underground press, has solidified its legality.

Thus Heads Together is something of a wonder tale. Kramer, an Australian writer and publisher, was born in 1980, well after virtually all of the major underground papers—the Los Angeles Free Press, Berkeley Barb, East Village Other, Austin Rag, Chicago Seed, and Rat Subterranean News among them—folded. (The great exception, Detroit’s Fifth Estate, once the province of the jazz poet and pot martyr John Sinclair, continues to this day as a militantly eco-anarchist triquarterly.) Kramer’s view of these chaotic publications is selective, subsuming individual writers and artists, as well as numerous issues, under the five-leaf symbol of the cannabis plant.