In the end, the best argument against the claim that impeachment requires criminality is not the overwhelming weight of contrary history and precedent, but the sheer dangerous absurdity of the proposition.

The British Parliament invented impeachment and the American Framers poached the institution as a means of saving their respective constitutions from tyranny or catastrophic mismanagement by hereditary, appointed, or elected rulers. It would be daft—and the Framers were not daft—to hobble this “indispensable remedy” by confining it within the idiosyncratic limits of the statutory criminal law available at any given point in time.

Both action and inaction by the chief magistrate, if sufficiently dangerous to the republic, must be impeachable if impeachment is to serve its intended purpose. Even conduct motivated by a sincere and deeply held principle can be a constitutional “high Crime.”

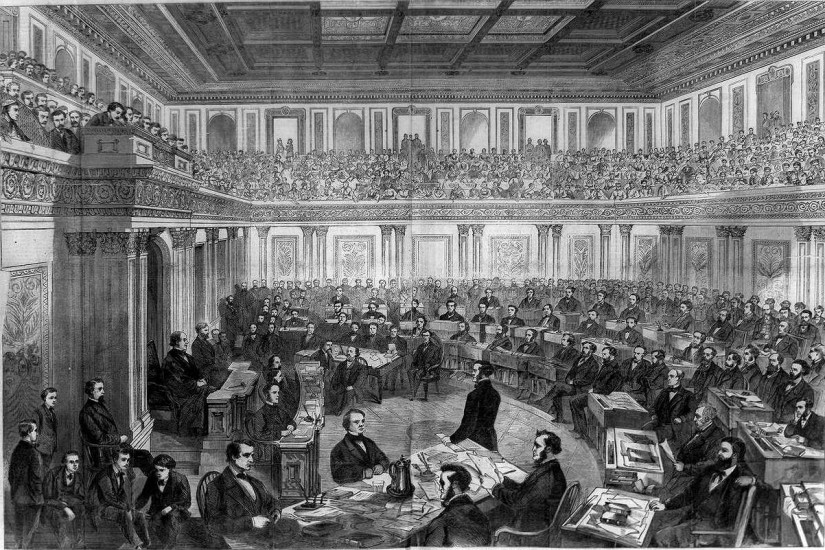

Ben Butler made precisely this point during the Johnson impeachment. Suppose, he imagined, that in 1861, when secession fever broke out, the president had been not Abraham Lincoln, but a man who, whether moved by fear or “an honest, but perverted political theory,” refused to mobilize the Union against the rebellion. Would we say the only remedy in such a case was to allow dissolution of the country because the president’s inaction was no crime?

Or suppose that the nation’s highest court decided Brown v. Board of Education and ordered the desegregation of American schools, and the president ordered out federal troops, not to enforce the order, but to suppress protests by black citizens who sought to take advantage of the order by enrolling in previously segregated schools. Would such defiance of both a co-equal branch and the dictates of common humanity be unimpeachable because it was noncriminal?

Or suppose that a president were to announce one morning that henceforth he would take no account of congressional statutes or administrative regulations and would instead rule by decree. That is, so far as I know, no crime. But does anyone doubt that such a decree would be impeachable?

Or suppose, to bring the case still closer to home, a president were to subordinate himself and the interests of his own country to a foreign power because he or his family could make money by doing so. Or because the foreign country agreed to help him secure reelection. Does anyone seriously suggest that the question of whether such behavior is impeachable turns on the niceties of ethics rules or campaign-finance laws?