America’s fundamental demography has changed markedly since 1968 and 1980. We’re a more diverse country, not only by measures of race and ethnicity, but by sexuality, family composition and lifestyle. Working-class voters have for some time shifted gradually to the GOP, just as college-educated white suburbanites—particularly, women—have made the opposite migration to the Democratic Party.

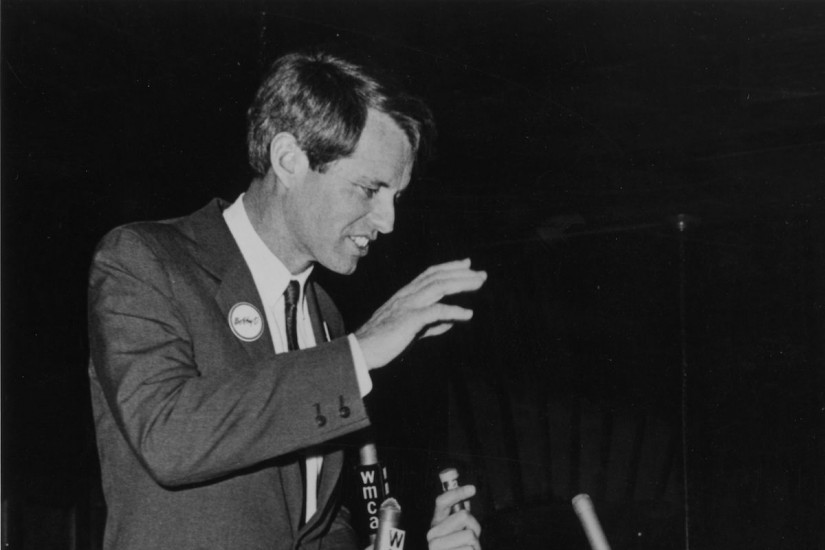

Yet on the week of the 50th anniversary of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, many pundits have found it tempting to locate in his last campaign the Democratic Party’s map out of the wilderness. That would be a mistake. The examples are instructive on a limited basis, but in both cases, context and contingency mattered.

Context: Bobby Kennedy ran for president at the high-water mark of white backlash, in a year when America seemed at war with itself. It’s possible that no candidate—even one so apparently hard-wired for the challenge—could have bridged racial and class divides. (Another candidate, Richard Nixon, knew how to profit from them.)

Contingency: Without a prolonged hostage crisis, Ted Kennedy might not have gained sufficient traction in the late primaries.

Context: Ted Kennedy ran for president in a transitional decade, when millions of Americans swung wildly between left and right. It was an era when women could be found at both feminist marches and anti-abortion rallies; union members could demand economic collectivism one day, and angrily oppose school busing the next. On Election Day, some 27 percent of Ted Kennedy’s primary supporters cast their votes for Ronald Reagan, including a self-identified white-ethnic liberal from Queens, who told a reporter shortly before the general election: “Carter’s a disaster. I think what the country really needs is a father figure, so I’m voting for Ronald Reagan.” In so fluid an environment, Ted Kennedy and Ronald Reagan could profit.

Contingency: What if RFK had lived and had taken the nomination from Humphrey? Ultimately, the 1968 election results were painfully close, with Nixon taking 43.4 percent of the popular vote to 42.7 percent for Humphrey and 13.5 percent for George Wallace. It’s not impossible to believe that he might have shaved off enough points from Wallace among white-ethnic and blue-collar workers in key East Coast and Midwestern states to win the race.