A few months ago, a New York Times investigation uncovered the secret economies of social media bots. C-list celebrities such as Paul Hollywood, John Leguizamo, and Michael Symon, purveyors of “fake news,” and several businesses have boosted their Twitter profiles by purchasing fake follower “bots” and retweets from these accounts. The Times estimated that perhaps as many as 48 million Twitter accounts are bots, with around 60 million similar accounts on Facebook.

This underground economy feeds on a manipulation of algorithms. More “likes” or “favorites” push a post up to the top of a feed. More links to a news article or a product boosts its ranking in search engine results. Bots raise the profile of particular topics and thus drive public conversation. As thousands of bots tweet about a particular issue, it begins to “trend,” alerting other users. Research has indicated that social media bots financed by the Russian government sought to manipulate the 2016 election by driving interest in particular hashtags, news stories, and topics.

This is surely cause for concern. But is it new? The bot economy and the seemingly-sophisticated algorithms of Silicon Valley, after all, are based on a powerful psychological vulnerability that has existed for centuries: attention begets more attention. People care about what’s engaging others. We are interested in what’s atop the best seller lists, the winners and losers at the weekend box office, and apparently even things like inauguration crowd sizes. Like Lin-Manuel Miranda’s FOMO-ridden Aaron Burr, we all want to be “in the room where it happens.”

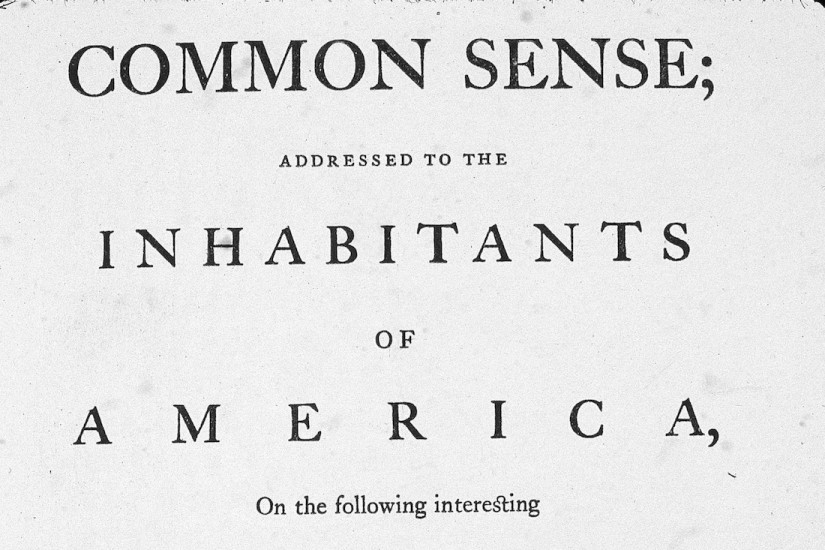

This principle was as true in the era of the American Revolution as it is today. In one of my favorite academic articles, scholar Trish Loughran shows that the illusion of a ubiquitous readership was essential to the impact of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense. Because they imagined that everyone had read it, Anglo-American colonists treated it not as a pamphlet but as a phenomenon.