Maybe it’s the odor, more than anything else, that identifies the experience of the circus—the strangely distinctive scent, the smell of it all: an aromatic assault that seems to plunge down the throat and seize the tonsils. It’s a complex odor, both insubstantial and yet somehow architectonic, like a circus tent. Like the big top itself.

The day before the circus opens, the company manager would gather the whole crew—roustabouts and elephant handlers, clowns and acrobats, tightrope walkers and jugglers—to help raise the canvas roof to the peaks on its poles, wafting above the fairgrounds the largest single piece of cloth most people would see in their lives. And early the next day, the crew would gather again to create the compound odor of the circus. The caramel smell of sugar burning on the cotton-candy machines and the faint reek of animal manure. Wood shavings and hot peanuts. Old dust shaken out of faded tents. The greasepaint and the popcorn. The sweaty hint of a ginned-up excitement, or maybe a tamped-down despair. Something, anyway, outside the ordinary and mundane. Something wonderfully unlikely and maybe disturbingly uncanny.

A circus, in truth, is redolent: a must of scents unlike any other. The question, of course, is, Redolent of what? And the answer seems to be: redolent only of other circuses. For Americans over, say, age 40, it’s hard to recall one’s first visit to the circus. They all blend together, one actual circus with another, and the sum mixing with circuses in movies and television shows and novels. The daring young men on the flying trapeze, the sad-faced clowns, the high-wire walkers, the tamers of wild beasts, even the besequined girls on horses, plumes on both their heads: They all seem to have been around forever.

As it happens, that’s wrong. The circus as we know it, as we picture its essential form, turns out to be a fairly recent thing. Popular myth typically traces the modern circus back to the ancient Romans, but as noted in The Circus, a fascinating new PBS documentary from American Experience, the American form was something surprisingly new in the world.

The most obvious roots lie in European displays of horsemanship. The rings of the traditional American three-ring circus, for example, derive from the equestrian rings that ensured good visibility for the audience and generated the centrifugal force needed to push riders against their mounts while they performed. The first European circuses were run by the teachers of schools of horsemanship, who eventually found they could make more money entertaining crowds in the afternoons than they could by charging students in the mornings.

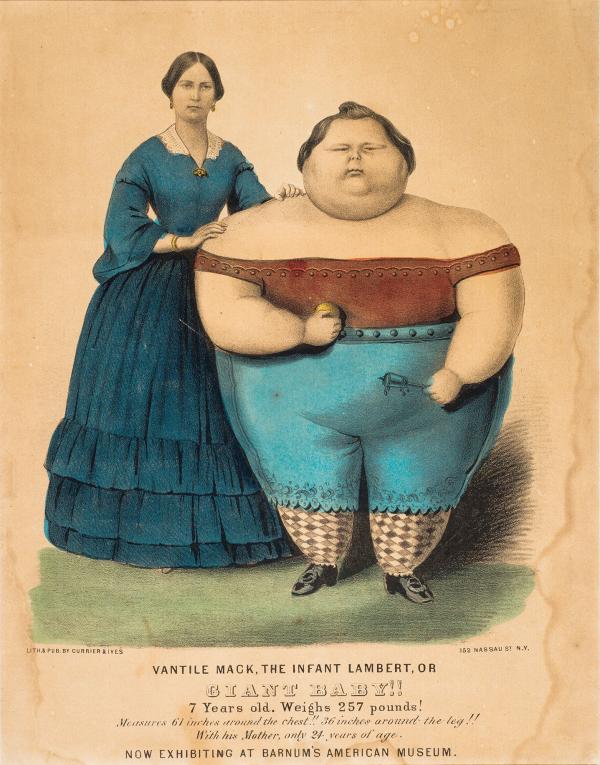

Among the Shelburne’s collection of circus posters are more than a couple that cry out for consideration as expressions of a proto-modernism. Exploitation, too, is an important thread running through advertisements for Barnum's American Museum, including this one for Vantile Mack, The Infant Lambert, or Giant Baby!!, ca. 1851.

—Currier & Ives, Vantile Mack, The Infant Lambert, or Giant Baby!!, ca. 1851. Hand-colored lithograph, 12 x 9 3/4 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum, gift of Harry T. Peters, Jr., Natalie Peters, and Natalie Webster, 1959-67.6.

Their hippodromes grew grander and grander until they rivaled the greatest opera houses. By 1844 the Cirque Olympique in Paris was home to both the circus and the national opera. The British equestrian Philip Astley is often named as the father of the modern circus, and, by the late 1700s, his Royal Amphitheatre in London boasted four stories of gallery seating, with a main floor that could accommodate operas, plays, and circus shows. Jane Austen mentions Astley’s in her 1815 Emma, and Charles Dickens records a visit in his 1841 Old Curiosity Shop: “Dear, dear, what a place it looked, that Astley’s; with all the paint, gilding, and looking-glass; the vague smell of horses suggestive of coming wonders; the curtain that hid such gorgeous mysteries; the clean white sawdust. . . . What a glow was that, which burst upon them all, when that long, clear, brilliant row of lights came slowly up. . . . Well might Barbara feel doubtful whether to laugh or cry, in her flutter of delight.”

It was Charles Hughes, one of Astley’s employees, who would leave to found the Hughes Royal Circus, Astley’s main rival. And John Bill Ricketts, one of Hughes’s employees, would in turn flee to Philadelphia in the 1790s to start up the first large-scale American circus.

Over the following decades, as the wagon trails and canals reached westward, circus tents rather than permanent structures came to define the American extravaganza. Performers on tour from Europe found few cities large enough to sustain expansive opera houses, but they quickly learned that there was money to be made performing brief shows to crowds of farmers at dozens of little burgs. And once the railroads began racing across the continent, the circuses leapt aboard, moving their menageries into stock cars and rolling their wagons up on flatcars. Eventually, with the development of the big-top tents and company-owned trains, American showmen created the circus as it would be known for more than a century.

It’s here, within the American tradition, that PBS’s The Circus chooses mostly to begin the story. The documentary’s stage was set by the success of Michael Gracey’s 2017 film The Greatest Showman—a musical about P. T. Barnum’s vain-glorious successes and eventual repentance. As The Circus shows, his real character was something more peculiar. Something much less palatable to modern taste.

In fact, peculiarity seems to define nearly everyone who helped create the American circus—not just Barnum, whom the documentary features prominently, but also his once famous rival Adam Forepaugh, and the Ringling Brothers, and even Barnum’s eventual business partner, James Anthony Bailey. The Circus presents a compelling case that the interplay of these entrepreneurs shaped what Americans still picture when the word circus is spoken.

Thus, the indomitable and self-promoting Barnum, thriving despite numerous business catastrophes, was always seeking to outdo the pugilistic Forepaugh. And Barnum’s greatest success in that regard came when, in his seventies, he recognized the organizational talent of the decades-younger Bailey, secretly partnering with him while publicly proclaiming their implacable rivalry—a quintessential Barnum move.

That partnership, Barnum and Bailey’s, ruled the American circuit until Bailey’s death in 1906, when the business was acquired by Ringling Brothers. The behemoth combination, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, lasted until its closing in 2017, done in by the long decline of ticket sales.

Of course, that leaves the question of why ticket sales declined. The circus was always a bifurcated place—family entertainment seasoned with a smidgen of the forbidden and the aberrant. There was a vicarious suggestion of impending disaster, with the Flying Wallendas’ building human pyramids in the air. A titillating hint of the flesh, with women in tights parading in the center ring and peepshows tucked away in a corner of the fairway. A touch of the grotesque, a splash of the garish, a hint of the criminal.

Part of P. T. Barnum’s genius was to sand off some of the rougher edges. Seeking to improve the reputation of circuses, he promoted his menageries and grotesqueries as educational opportunities. He lined up ministers to praise the circus as wholesome entertainment rather than immoral indulgence and idleness. He advertised his hiring of Pinkerton detectives to assure circus-goers that they would not be pickpocketed.

But the other part of P. T. Barnum’s genius was not to sand off too much. He still made a fortune from the dwarfism of Tom Thumb. He still had bearded ladies and conjoined twins. He kept the danger of trapeze artists working without a net and animal tamers with wild beasts. Through all his innovations, he preserved something of the strangeness of the circus, something of the alien and the exotic.

His successors tended to do less well. Through the twentieth century, accelerating into the twenty-first, every change brought about a normalizing of the circus, cutting into its uncanny core. Disneyland was built on this model, of course: opening in 1955 as, essentially, the old experience of the fairground and amusement park with all the seediness purged. But, as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey discovered, Disney always proved best at doing Disneyland. The circus without its dodgy elements is no longer a circus.

Even while the circus owners were trimming the circus to accommodate what they thought were changes in the culture, the culture was changing faster still. With OSHA laws and mandatory liability insurance, the culture demanded safety in a show whose business was the unsafe. With the sexual revolution and the rise of easy pornography, women in tights on horses ceased to seem transgressive. With the shrinking of the world, African animals no longer appeared exotic. With the information economy of the Internet, P. T. Barnum’s brand of outrageous hoaxes was too easily debunked. With the rise of animal rights activism, the parades of elephants and caged cats were increasingly banned.

The circus in its heyday showed a little of the fantastical to ordinary people. Small wonder that sideshows prospered, however outlandish and exploitative the claims shouted by P. T. Barnum’s barkers: A real unicorn! Siamese twins! Jo Jo the Dog-Face Boy! He walks, he talks, he crawls on his belly like a reptile! If such elements appear in modern circuses—from the acrobatics of the Cirque du Soleil to the hokeyness of the Shrine Circus—the references are firmly ironic, aware that their audience is in on the joke.

Just a few decades ago, moviegoers still routinely clapped at the end of films. Today, ringmasters routinely have to badger audiences to applaud the circus stars—each of whom, as live performers, needs the energy of a reactive audience. So, as modern viewers withdraw, performance takes on a kind of heartache, like a failed romantic gesture. The fire swallower now somehow more desperate and less daring. The spandex-clad woman rotating inside the gyroscope the object only of a quiescent lust.

It wasn’t always so, and in the long decades of the decline, we’ve lost something that the circus once provided—some integration of the unlikely and uncanny. For all of P. T. Barnum’s braggadocio, the truth is that just a little twist could make it all seem wicked. The notion of evil clowns, for example, has become a modern meme. The presentation of circuses in movies has often been dark—even as far back as Cecil B. DeMille’s 1952 classic The Greatest Show on Earth, with Jimmy Stewart playing a criminal using his greasepaint to hide from the law.

Circus tunes were always peculiar. The one piece most associated with the center ring, Julius Fučík’s 1897 Entrance of the Gladiators, opens with a tumble of chromatic scales. But almost any oom-pah-pah waltz melody can be made to sound like an ominous circus, if layered with a few chromatic runs, stacked with tritones, transposed to a minor key, or played on something spooky like a child’s music box.

Circus performer, Zelda Boden, circa 1910, from American Experience: The Circus.

—Collection of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida, Florida State University

Think, for a moment, of how circuses used to be. Each summer, eye doctors and dentists, and the old farmers at church, would cheerfully distribute tickets to children as the circus drew near. And something in their enthusiasm was contagious. The air seemed charged, the entire town electric, as though set in a kind of time outside of time. Townsfolk would make unnecessary detours to drive by the fairgrounds, watching the circus trucks unload. We could see the tension being cranked into the guy wires, a worker testing the cable with a calloused thumb and sending out a metallic thrum, as though to say: The circus! The circus is here! The circus has come to town!

And then the tattered, patched tents, faded from years of hard sun. A diesel generator rattling behind the stands. A grim woman selling lipstick-red candy apples, her face like a half-remembered photo on a post office wall. A large fan by an open tent flap to fight the swelter, only adding noise without moving air. The lions panting in a cage near one of the side rings. A clown directing five dogs so old that the audience would wince each time a dog leapt through a hoop.

The familiar had not gone away, exactly. In the summer heat, people would fan themselves with anything handy: a paper popcorn tub torn open, a folded church bulletin scrounged from a purse, even ticket stubs splayed like playing cards. But the unfamiliar had also taken hold, like the ordinary-looking woman in the side ring who suddenly proved a contortionist, wrapping her legs behind her head. The high-wire act held us rapt as the performers risked their falls. A small protest would escape the crowd as the lion tamer put his head in the mouth of a beast. The clowns didn’t make us laugh, exactly, but they made us smile. A plumed woman posing on the back of a prancing horse. The ringmaster in his top hat and red coat, white jodhpurs and black boots, directing our eyes to each new act with a flick of his baton.

Through it all, the strange compound scent of a circus would waft, reminding us of something not quite present—superimposing on this circus all the circuses that have ever been.

Originally published as "Running Away with the Circus: How the Big Top stole our hearts" in the Fall 2018 issue of Humanities magazine, a publication of the National Endowment for the Humanities.