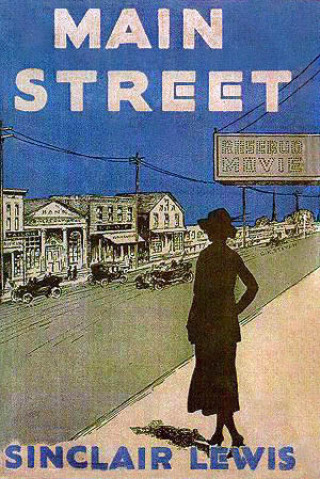

Why has The Age of Innocence endured? It and Main Street are alike in being almost anthropological explorations of tribal cultures: the former of upper-crust New York society in the 1870s, the latter of small-town Minnesota in the 1910s. Both are “hieroglyphic worlds” (Wharton’s phrase from The Age of Innocence) of brittle convention under which the human spirit roils. The protagonists of both rebel against society, but ultimately give up. Yet, while Main Street is supposed to be a naturalistic masterpiece (to the point, I would argue, of tedium), The Age of Innocence offers more: there is something elegant and complicated going on with its poetics (Wharton is a strikingly sophisticated writer without ever being showy), and the final chapter of the book leaps forward in time in such a way that the novel devastatingly captures the passage of an era. The author Colm Tóibín tells BBC Culture that he thinks of it as a “stylish book about disappointment, written… by someone who knew that world but is clear-eyed rather than nostalgic about its demise”.

The shift to modernity

Wharton was living in Paris during the Great War and threw herself into the war effort, “working on behalf of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who flooded across the French border”, as the writer Elif Batuman (herself shortlisted for a Pulitzer this year) notes in her foreword to the new Penguin edition of Age of Innocence. After the war, a changed person, Wharton sat down to write about how the Gilded Age of her girlhood had yielded inexorably to modernity. Janet Beer, professor of literature at Liverpool University and a Wharton expert, tells me that she regards The Age of Innocence as “an almost perfect example of the genre of historical novel”: it “has her at the height of her powers and totally in control of the subject, the genre, and the conviction that this was the only way to commemorate a society now dead”.

To get a sense of what a gilded cage the Gilded Age was, watch Scorsese’s film and marvel at the canyons of mahogany and reefs of crystal these people swam through – the hushed, heavily encrusted formality of an upmarket funeral home. Tóibín, in his introduction to the Scribner edition (2020), calls this the “twilight time” of the old New York aristocracy. Twilight indeed. The novel signals that the “elaborate futility” of an elite way of life, in which work features as a hobby, was about to be overcome by what Beer calls “the unstoppable power of new money, financial profiteering, rising materialism, and family breakdown”. It is an unsentimental modernist critique of a genteel stratum of society for whom the 20th Century figures as a storm on the horizon.