How should we remember the Civil War? For many liberals today, the story is one of the North winning the war but losing the peace, acquiescing to a sectional reconciliation that left white supremacy intact. Racism won out, plain and simple.

But this is only part of the story. The precipitous decline in union membership, labor militancy in the workplace, and Marxist scholars in academia have conspired to obscure what historian Matthew Stanley brings to light in his recent book: that the Civil War, for black and white workers alike, was an enduring touchstone for popular struggles from Reconstruction to the New Deal, shaping class consciousness in the process.

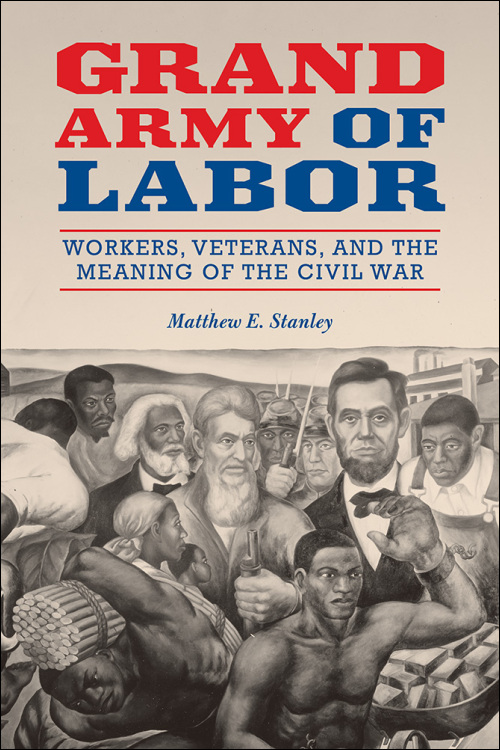

Grand Army of Labor: Workers, Veterans, and the Meaning of the Civil War shows how industrial workers, farmers, and radicals deployed an “antislavery vernacular” in their struggles against Gilded Age and Progressive Era capitalism. They cast themselves as the natural torchbearers of the antebellum free labor ideal, which, they argued, targeted not only chattel slavery, but wage labor — heralding what Karl Marx envisioned as a “new era of the emancipation of labor.”

Stanley details the collective construction of a “red Civil War,” built by radical workers in countless trade union halls, workshop floors, and third-party soapboxes. In this crimson-hued vision, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln featured as paragons of abolitionism, the vanguard of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “abolition-democracy.” And although the Union Army had crushed the landed aristocracy of the Slave Power, capitalist expansion had bred new monied interests and created new forms of corporate dominance. That despotism called for a new generation of emancipators.

“War Gave One Kind of Master for Another”

The Knights of Labor — a trade union federation founded in 1869 that reached a peak of 800,000 members in the mid-1880s — was one prominent organization that brandished Civil War language to fight “wage slavery.” “War gave one kind of master for another,” one Knight explained at a Blue and Gray Association meeting in 1886, “and wealth once owned by the masters of the South has been transferred to the monopolists of the North and multiplied a hundred-fold in power, and is now enslaving more than the war liberated.” The Knights advocated a class-based, cross-racial alliance to wage this next stage of the war for emancipation. They proved remarkably adept at organizing black southerners — and convincing their white counterparts of the necessity of it.