RFID is, of course, not the first novelty to be singled out as the Mark of the Beast. A famous image from the fierce vernacular art of twentieth-century American biblical tracts shows a Satan-figure, rising above Saint Peter’s Square and a multitude of human corpses, clutching an executioner’s axe. The words “666 VISA” are emblazoned on his broad chest. Radio-frequency identification technology thus merely figures as the latest supposed harbinger of the end times in a culture obsessed with both the apocalypse and technology. “We’re going into some strange worlds ahead of us, ladies and gentlemen,” Robertson warns. He’s not wrong.

These anxieties about the entanglements of human life and technology, of the movements of the body mapped onto the geographies of power, have a deep pedigree in Judeo-Christian thought. Biblical scholar Robert Alter notes that, as early as Exodus 30:12, when a census of Moses’s people comes bundled with a “ransom” of a half shekel in symbolic exchange for the counted’s life, there has been “a folkloric horror of being counted as a condition of vulnerability to malignant forces.’” Beginning in the Davidic narrative of the Book of Samuel, Israel’s most famous monarch chooses to count his subjects, with disastrous results. Mapping and counting, in these stories, acts as a sort of dowsing rod, auguring the collision course between the profane world and the divine. This is only cast in deeper relief by the long obsession America has had with its own teleological importance. Puritan ideologues sought to establish their utopian City on the Hill. In the post-Revolutionary years, influential preachers such as David Tappan and Timothy Dwight, of Harvard and Yale respectively, proclaimed the young republic’s providential role in world history, laying the groundwork for the Second Great Awakening.

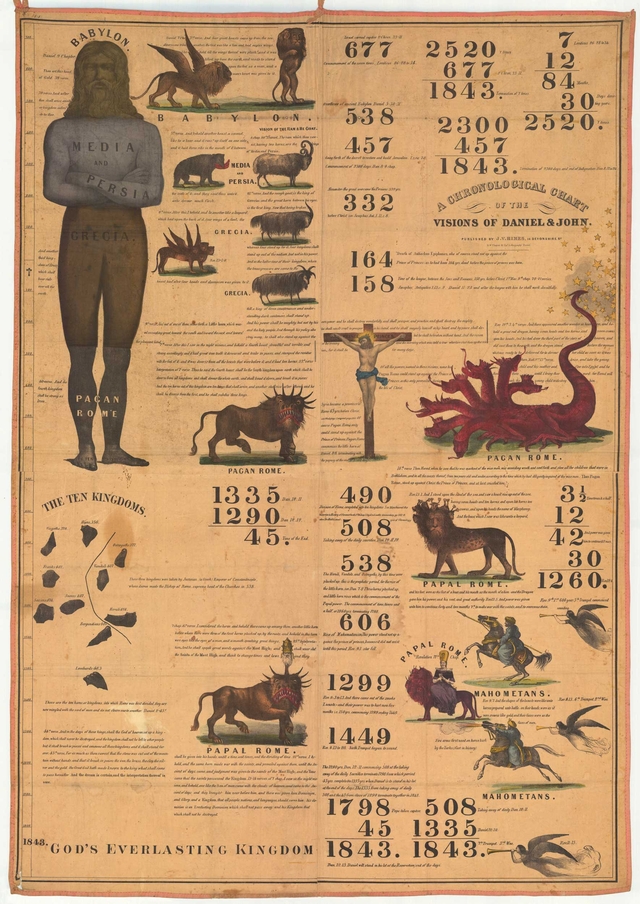

Prognostications of doom abounded in nineteenth-century and twentieth-century American folk cultures. In his work on popular eschatological beliefs in early twentieth-century Ohio, folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett recorded “cows lowing at night, bad thunderstorms” and the sudden fashion of women wearing “glass high heels” as a sure indication that the end times had arrived. This very twentieth-century image, which seems to mingle the quiet surrealism of advertising displays with the cryptic visions of the Revelator, combines consumerism and apocalypticism in a disquieting manner. An undercurrent of anti-government thought has long informed this particularly American brand of eschatological belief.