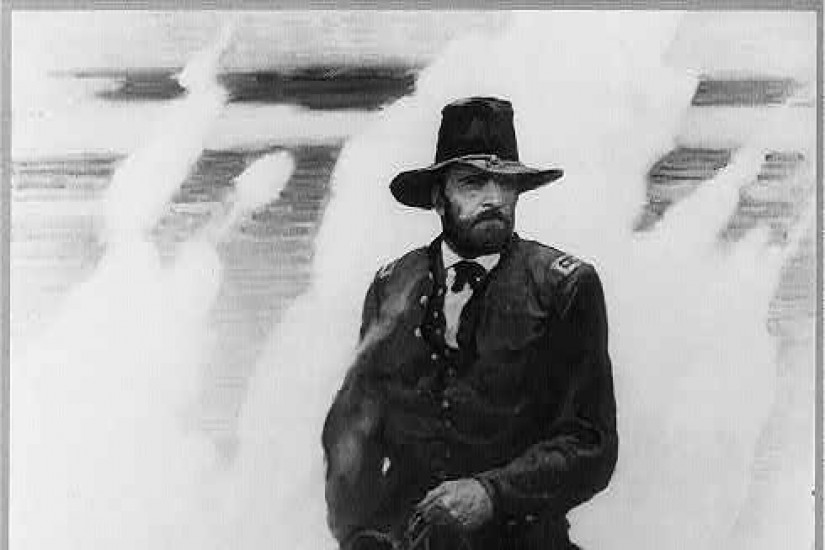

Ulysses S. Grant was a hero to his generation: the greatest general of the Civil War, a popular president who was elected twice—and could have been elected three or four times had he wished. But later generations found him entirely dispensable, and he became the butt of historians’ jokes. Surveys of presidential scholars long placed Grant among the worst presidents. In a 1948 poll he rated ahead of just Warren Harding; by 1982 he had only clambered past James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson. And while today he has managed to put a little more distance between himself and last place, it is still no surprise to find him in the bottom half, if not among the bottom ten.

The standard rap on Grant is that he was a drunk who surrounded himself with spoilsmen who stole the country blind. In an era of scandals—the Crédit Mobilier’s siphoning of millions in the construction of the transcontinental railroad, the Tweed Ring’s bilking of New York in awarding city contracts, the Whiskey Ring’s dodging of the tax on booze—Grant was said to turn a blind (or drunken) eye to all manner of wrongdoing. Beyond that, the simple soldier was over his head in the White House. At a time of rapid economic change, he hadn’t a clue how to manage an increasingly sophisticated economy.

Considering the current state of the American economy, this last charge might now be the most damning, if true. But it’s not true. And Grant’s surprisingly sophisticated handling of economics, especially in the wake of the Panic of 1873, suggests that he deserves better from the historians than he has been getting.

The Panic of 1873 began like every other financial panic. Certain speculations were too tempting to resist; investors told themselves that this time things were different. The law of gravity no longer applied; what was going up would not come down. On occasions past, the temptations had been tulips and western land; now it was western railroads, which would tame the wild Indians, fill the frontier with farmers, and return profits from their traffic for decades. The premise was sound; the West would indeed yield profits for the railroads far into the future. But the profits did not come soon enough to redeem the extravagant promises made in their name. In September 1873 the Philadelphia firm of Jay Cooke, the financier who during the Civil War had sold a billion dollars in bonds that fed, clothed, and armed the soldiers of the Union, shuttered its doors. Jay Cooke & Co. had undertaken to underwrite the Northern Pacific Railway, which it pitched as the gateway to the Eden of the Pacific Northwest. But some invisible tremor, some inaudible signal caused investors to shy at the bonds, and the firm suddenly couldn’t meet its commitments.