With cries of cronyism greeting the nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court, the White House is appealing to history—saying, in effect, that there’s a long and distinguished tradition of cronyism in Supreme Court appointments. And they’re right: From Andrew Jackson to Lyndon Johnson, many presidents have put their confidantes on the bench. But the White House claim omits a key fact. The practice of naming presidential pals began to wane decades ago, and, as John Roberts might say, the wisdom of avoiding cronyism is now a settled matter. The question is whether the Miers choice represents a one-time relapse or a harbinger of things to come.

Dismay about cronyism in America dates back to the 1830s, when government by the elite gave way to a more inclusive and contentious democracy. With democratization and party politics came the spoils system—a name derived from New York Sen. William L. Marcy’s gloating remark, “To the victor go the spoils”—under which the party that wins an election doles out the rewards, including jobs, to its supporters. If such raw patronage strikes us today as unseemly, it appealed to populists like Andrew Jackson as a democratic reform—a blow against the aristocratic strains of the early republic. Of course, not everyone agreed.

In distributing offices to friends, Jackson deemed the Supreme Court fair game. In his two terms he appointed six justices, many of whom had helped him politically in some fashion. Most controversial was his choice of Roger Taney, who had been a crucial ally in shutting down the Bank of the United States. After an angry Senate refused to confirm Taney as treasury secretary, Jackson vowed to strike back, and when a high court vacancy opened in 1835, he did. Although the Senate rebuffed Taney’s nomination at first, Jackson got the last laugh, nominating his friend again later that year when Chief Justice John Marshall died. Taney served as chief justice for 28 years.

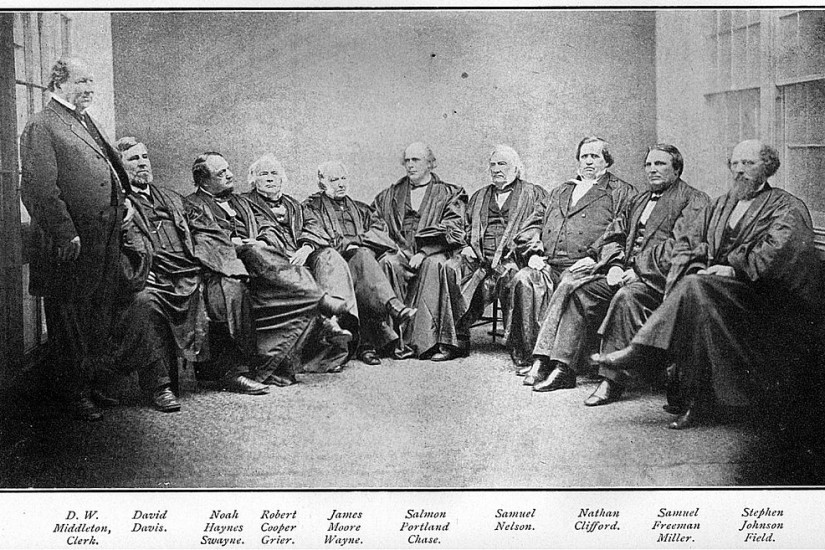

In time, Jackson’s habit of naming friends to the bench became fairly routine. In 1862 Abraham Lincoln appointed David Davis, a brilliant Illinois judge who had pushed Lincoln’s Senate candidacy in 1858 and served as his campaign manager in 1860. Rutherford B. Hayes nominated two men who had worked to secure his dubious election, John Harlan and Stanley Matthews. Chester Arthur—who after a hacklike career surprised everyone as president by championing clean government—chose two meritorious justices, yet stumbled by naming his longtime sponsor, the former New York senator and political boss Roscoe Conkling, to a Supreme Court vacancy in 1882. (Though the Senate confirmed Conkling, he amazingly had the good sense to refuse to serve.)