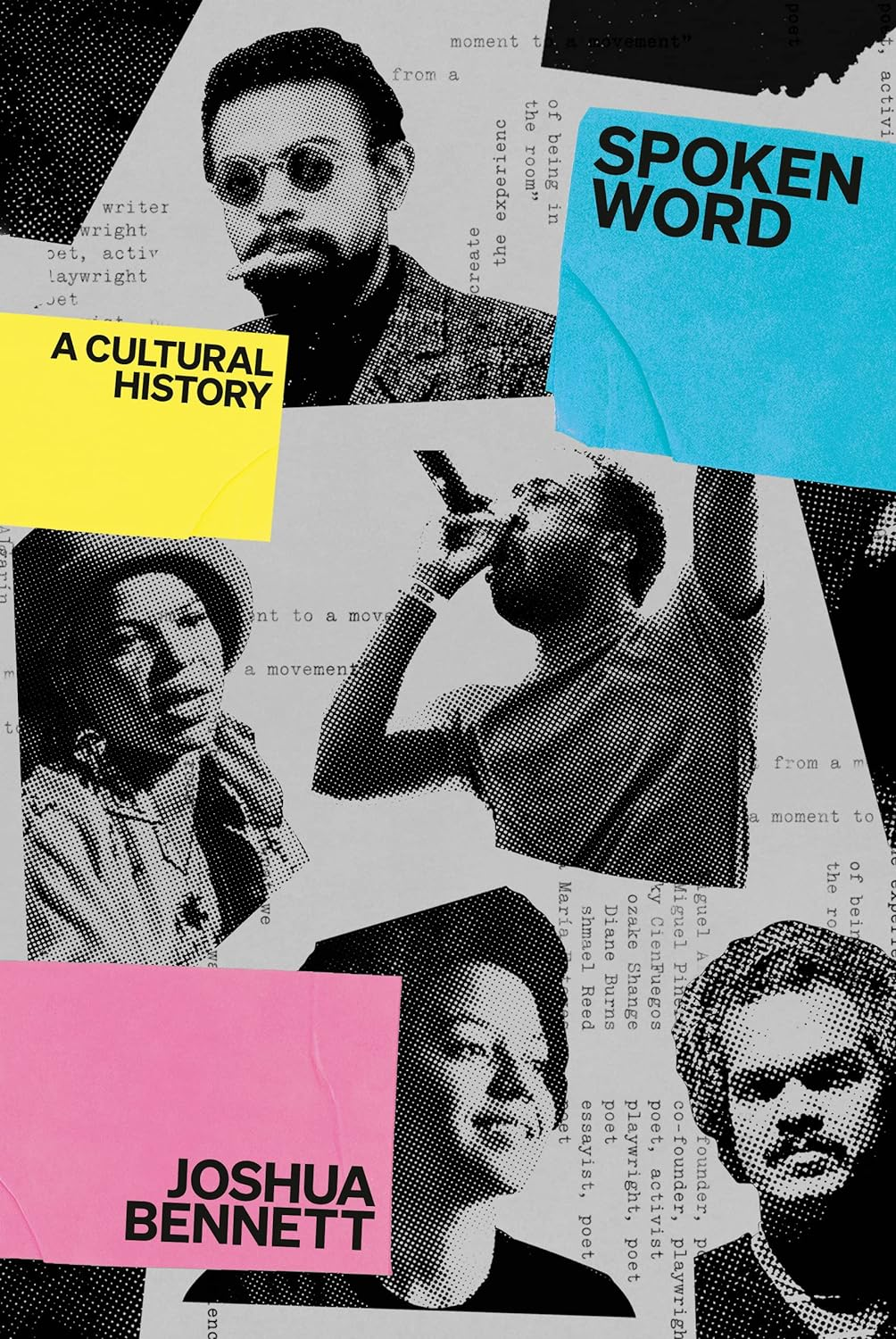

Early in Spoken Word: A Cultural History (Knopf, 2023), Joshua Bennett assures the many parties keeping vigil over poetry that the ancient art remains alive and well in the United States. “Spoken word is the best possible rejoinder to anyone claiming that poetry in this country is dead or not relevant to younger generations,” he writes. The curiously evergreen and SEO-friendly question of whether poetry matters has been posed so often this millennium that, in 2014, the Los Angeles Review of Books responded with an essay titled “How Much Does ‘Does Poetry Matter’ Matter?”

Although the late literary critic Harold Bloom disparaged slam—a competitive form of spoken word—as “the death of art” in 2000, its attitude, aesthetics, and techniques seeped into films, TV shows, music, and other art forms around the world. Bennett details this global footprint in Spoken Word, but he never treats his tour of the genre, which he defines as verse crafted to be performed for an audience, as a victory lap. For him, spoken word isn't interesting because it won the culture war against stuffy academics and their dusty canons; the value of spoken word lies in how it reared and continues to nurture its own culture. And in his view, that heritage of autonomy and aegis should shape how people understand it.

Bennett, a repeat slam champion who writes poetry and criticism, has intimate knowledge of his subject but approaches it with humility and imagination. He threads research, interviews, autobiography, and close readings of poems and related texts into a nonlinear jaunt through the spoken word archives. Perhaps in deference to prior books, such as Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz’s Words in Your Face (2007) and Susan B. A. Somers-Willett’s The Cultural Politics of Slam Poetry (2009), he does not attempt an exhaustive account. He’s more interested in highlighting the genre’s radical and communal roots and views history as a means of rekindling that rebellious upbringing. “I hope to reclaim the political ethos and persistent dreaming of a moment that is both part of our shared past and still among us,” he writes, alluding to the legacy of activism in spoken word circles. Even readers who don’t share Bennett’s political investment in spoken word will appreciate his use of our and us, which underscores the welcoming spirit of his project. At its core, his history invites readers to appreciate spoken word's myriad contributions to the arts, community organizing, and self-expression. Its culture, as he shows, surrounds everyone.