This first summer under the Trump regime resembles the long red-hot summers of the past. It has been filled with demonstrations, deadly clashes, and tenuous confrontations between white supremacists and anti-racist protesters. Trump’s inept responses to these moments of national reckoning have only fueled “both sides” garnering praise from known Ku Klux Klan (KKK) leaders and a bevy of white Americans claiming that “#thisisnotus.” The latter is a familiar but unwelcome refrain for many Black Americans who are tired of being comforted by specious hashtags instead of substantive engagement in the insidious nature of white supremacy. Indeed, today’s call for white liberals to “get their people” mirror those of some activists in the 1960s who suggested that white liberals should organize in their own communities and neighborhoods where white supremacy is “most manifest.”

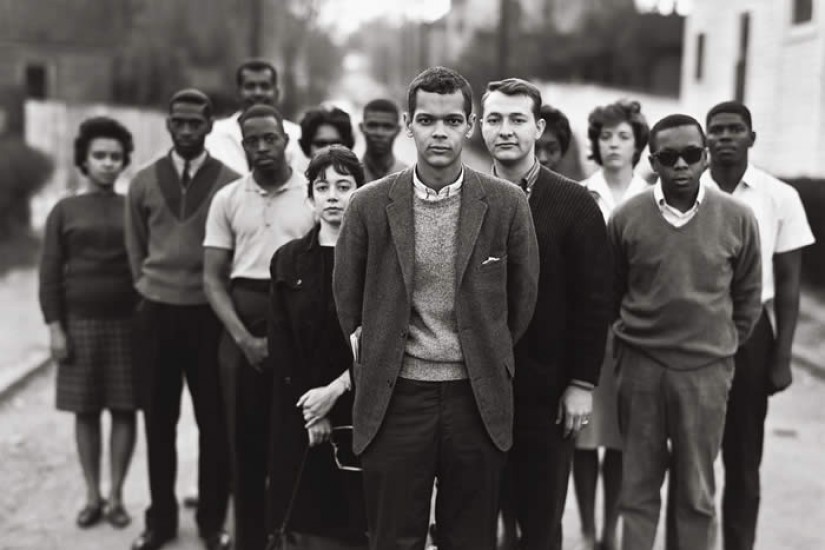

The Atlanta Project—a group of organizers associated with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)—were among the most ardent proponents of this claim. As members of the activist group founded in 1960, they were keen supporters of SNCC’s voter registration drives, community consciousness raising, school desegregation, and civic engagement in Atlanta and across the country. The group, which included Zohara Simmons, Gwen Patton, and Bill Ware, among others, worked to re-elect fellow member Julian Bond, when he was denied his seat in the Georgia State Legislature because of his support for SNCC’s anti-Vietnam War position. They also mobilized residents of the working-class Black Atlanta neighborhood, Vine City, to combat poor wages, housing and transportation inequality, and voter suppression.1 The mobilizing struggles they faced, coupled with SNCC’s changing composition, led Atlanta Project members to question the racial politics of political organizing.

In 1966, Atlanta Project members produced a paper that summarized their position on “the future roles played by white personnel” in the movement. The Georgia-based group acknowledged the important role white liberals had played in SNCC, and civil rights protests writ large. However, they also identified ways in which their participation undercut movement goals. Specifically, Atlanta organizers were concerned about white liberals’ “inability to relate to cultural aspects of black society,” “white-sponsored community myths of black inferiority” that come into play during organizing, and the “unwillingness of whites to deal with the roots of racism” within the white community. They also suggested that while well-meaning, a paternalistic ethos undergirded some white liberals’ participation in movement projects.