On May 19, 1930, Sadie Morlok of Lansing, Michigan, gave birth to identical quadruplet girls. Sarah, Edna, Wilma, and Helen were local celebrities from the get-go: reporters hovered in the hospital waiting room hoping to bribe nurses for the weight and length of the newborns; photographers snuck into the nursery to snap pictures. City officials offered the family free housing for a year, Lansing businessmen opened college savings accounts, and local seamstresses sewed diapers and blankets. In the bleak post-Depression years, everyone was looking for a silver lining—and the Morlok sisters fit the bill as the embodiment of cheerful white American girlhood. The family was quick to comply with public expectations. Sadie enrolled the girls in singing and dancing lessons, and took the quartet on the road, gussied up in frilly short dresses and ribboned curls. In an age of eugenics—a science their German-born father Carl put great faith in—the quadruplets doubled as examples of what wholesome breeding among strong white American stock could do for the country.

By their early twenties, all four of the quadruplets had succumbed to schizophrenia, and three of the four would spend the rest of their lives, until their deaths in the early 2000s, in and out of state mental hospitals and halfway houses. Once prized for their Shirley Temple dimples and shiny matching tap shoes, the sisters’ greatest attraction became something else entirely: they offered psychologists “[a]n unprecedented opportunity for the study of heredity and environment in mental illness,” according to a 1964 book review published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. In 1954, when the sisters were 24 years old, their case came to the attention of Dr. David Rosenthal, a schizophrenia expert at the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, DC. He secured the sisters’ transfer to NIMH’s facility where, over the next three years, they would be studied by a team of more than 30 medical doctors, social workers, and psychiatrists. In 1963, these studies culminated in Rosenthal’s 600-page pseudonymous landmark study, The Genain Quadruplets: A Case Study and Theoretical Analysis of Heredity and Environment in Schizophrenia.

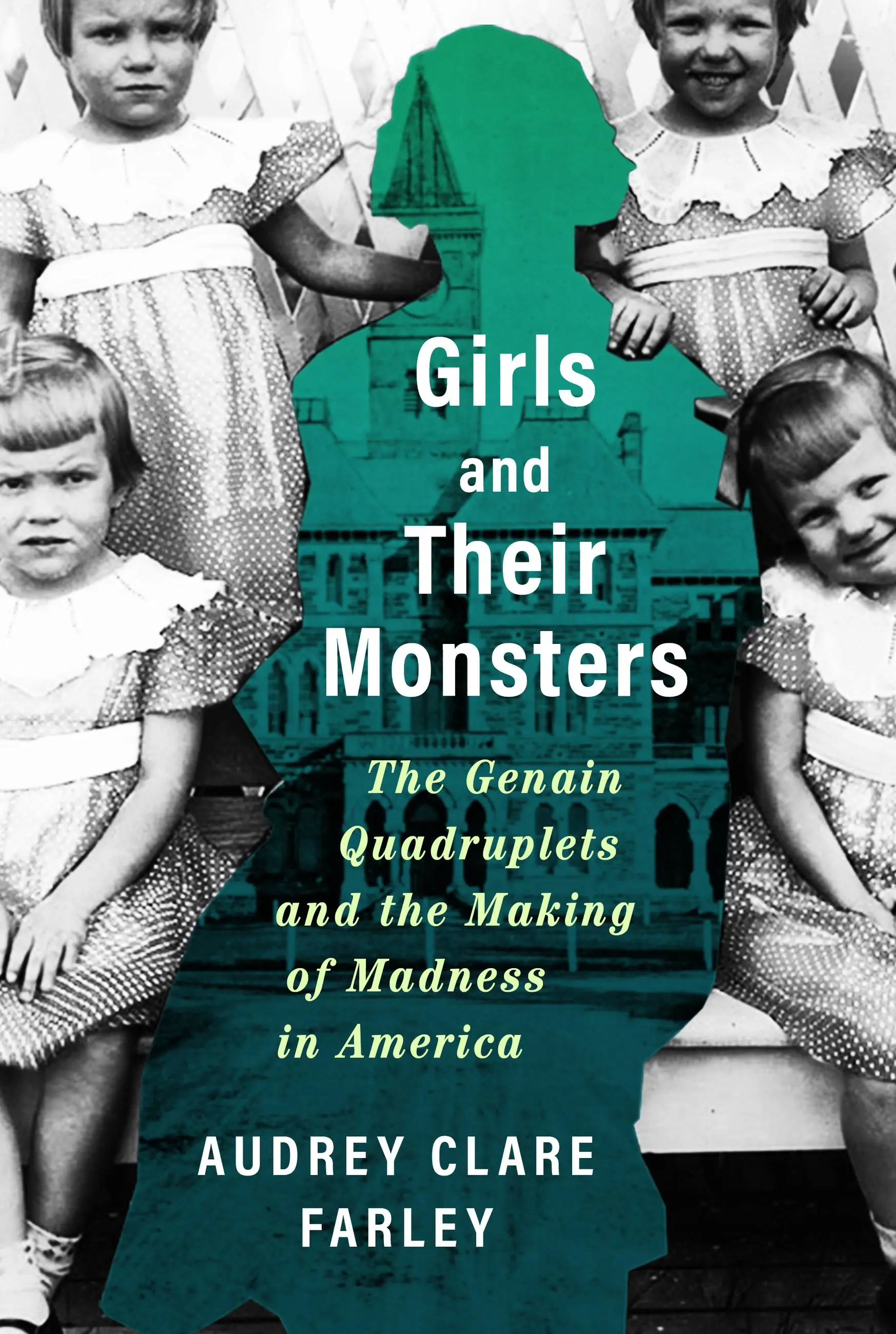

How was it possible that these sisters, once hailed as shining examples of American genetic fitness, had joined the ranks of the so-called eugenically unfit, emblems of degeneracy and a drain on the taxpayer’s wallet? This is the fascinating story that Audrey Clare Farley’s new book, Girls and Their Monsters: The Genain Quadruplets and the Making of Madness in America, sets out to investigate. In constructing an intimate portrait of the decades-long relationship between the Morlok family and the federally funded scientists who studied them, Farley examines the way American institutions and culture crucially shaped the construction of madness at mid-century. In the process, she raises vital questions about the nature of “psychosis” itself, both individual and collective.