In order to minimize labor costs as much as possible, the commissioners chose to utilize enslaved labor for the Federal City’s construction, resolving in 1792, “to hire good labouring negroes by the year, the masters clothing them well and finding each a blanket, the commissioners finding them provisions and paying twenty-one pounds a year.”

This course of action was not a new one, as many local slave owners had been hiring out their enslaved laborers to neighbors and businesses for some time. Owners collected a wage while continuing to provide clothing and some medical care. The commissioners typically provided workers with housing, two meals per day, and basic medical care. This arrangement allowed the nascent capital to reap the benefits of labor without bearing total responsibility for the workers’ general wellbeing. If an enslaved worker did not show up to work, the overseer simply docked the pay given to the owner. These enslaved laborers worked alongside white wage laborers and craftsmen on two of the largest construction projects, the U.S. Capitol Building and the White House.

As the major building projects progressed and the federal government prepared to vacate Philadelphia, the population of the District grew rapidly. Prior to the creation of the Federal City, the area was largely agricultural and rural. By the time President John Adams moved into the White House on November 1, 1800, the District of Columbia population had reached 8,144. Around 25% of those residents were enslaved.

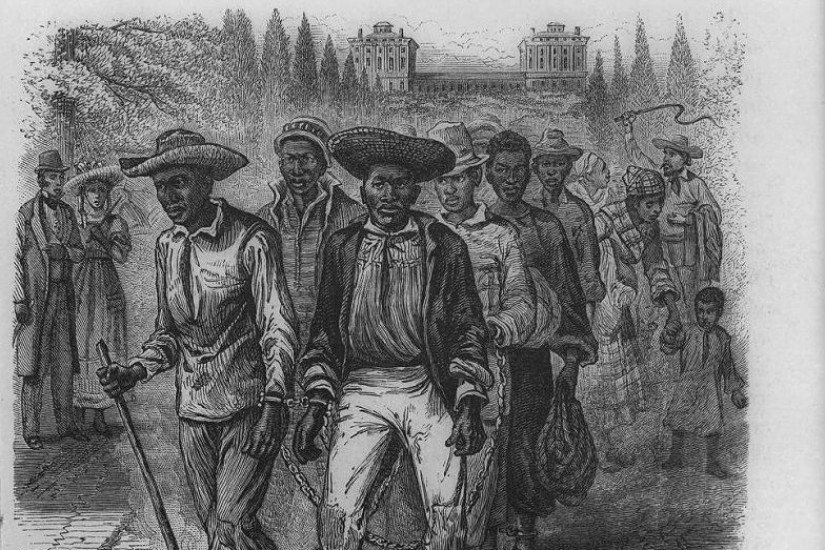

Carved out of two slave states, the city quickly became a hub for the domestic slave trade. As the tobacco industry in the Upper South fell into decline, so did the need for large numbers of agricultural laborers. Many slave owners decided to sell their enslaved workers to dealers based in Washington, D.C. These dealers imprisoned enslaved people in crowded pens for weeks or months before selling them to the Deep South, where the cotton industry had expanded exponentially. Some of these slave pens were within view of the U.S. Capitol Building, and the enslaved, shackled together in coffles, frequently trudged past the Capitol.

Enslaved people also toiled in the White House. At least eight of the first twelve presidents brought enslaved people with them to the White House. Others may have hired out enslaved people to work in the President’s House. These enslaved workers performed many duties, serving as cooks, valets, footmen, coachmen, maids, stable hands, gardeners, and more. All of the enslaved people at the White House worked for little to no pay. Although some presidents, like Thomas Jefferson, provided their enslaved workers with a small “gratuity,” this did not change the fact that they were legal property, owned by some of the most powerful men in American history.