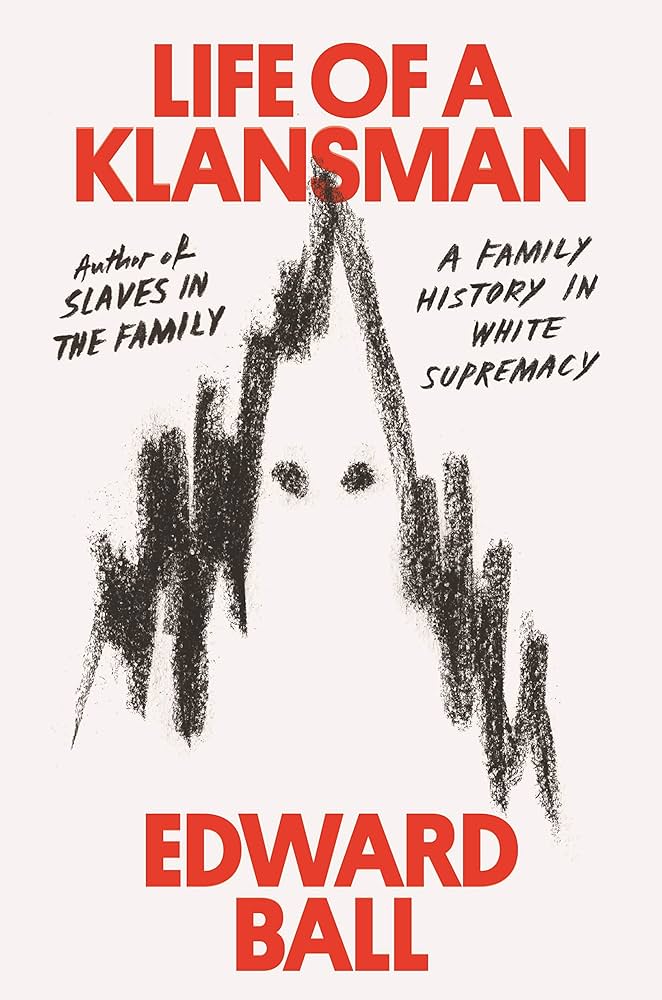

Among those implicated in the fledgling Klan’s earliest atrocities was a Louisiana carpenter and former Confederate soldier, Polycarp Constant Lecorgne, a great-great-grandfather of the writer Edward Ball. In Life of a Klansman, Ball presents the story of his ancestor as a case study in the enduring legacy of slavery. The book is part memoir (exploring family lore of how Lecorgne became a Klansman), part history (conjuring the antebellum South, the Civil War, and Reconstruction), and part discursive essay (with reflections, for example, on the invention of whiteness).

Ball recognizes that Lecorgne, a French-speaking Creole who lived most of his life (1832–1886) in New Orleans and fought to maintain the primacy of whites, was a “family hero of sorts…before standards changed, and his memory became too hot.” Nonetheless, he was still considered by some, like Ball’s aunt Maud, to have been a “Redeemer [who] helped to end Reconstruction,” and “for a long time, nobody said that was a bad thing. Except perhaps the Negroes.”

Ball’s earlier excavation of family history, the National Book Award–winning Slaves in the Family (1998), concentrated on his father’s side, “one of America’s oldest and largest slaveholding clans,” and in researching it he tracked down descendants of those his ancestors had enslaved. They included Leon Smalls, who doubted whether a white supremacist mentality had ever disappeared after the end of slavery:

“We today think that things have changed…. I work with a group of people who, the only difference is they leave their sheet at home. But they still have them in their closets.” [Smalls] was referring to the hoods and sheets of the Ku Klux Klan, though neither of us let those words pass our lips.

In Slaves in the Family, Ball largely eschewed writing about the family of his mother, Janet Rowley, who was born in New Orleans and, like her husband, had a plantation heritage. Ball recalled, “A yellowing photograph of the Seven Oaks mansion used to hang in the hall of our house…. By the time of the photograph, the plantation had long passed out of the family and stood abandoned and decrepit.”

This relatively poorer side of Ball’s family (which included Constant Lecorgne), whose fortunes faded after the Civil War, is explored in Life of a Klansman, a further confrontation with the toxically interconnected lives of blacks and whites. Lecorgne’s tale may have been a family secret, but Ball argues that, directly or indirectly, all Americans have skin in this game. By 1925, a decade after the release of The Birth of a Nation, the KKK could claim five million members, which suggests, according to Ball, that today one half of the white US population has a family link to it.