When I was a 12-year-old kid in Colombia, I discovered the banjo and fell in love with its sweet, metallic sounds. It happened while watching the 1999 documentary Steve Martin: Seriously Funny. The famous comedian — described by his sister as “obsessed with the banjo” — explains how he taught himself the instrument by listening to 33 rpm records “and slowing them down to 16 to pick up the banjo songs note by note; I down-tuned the banjo so it would be in the same key of the record. And I just kept playing.”

The movie ended, and suddenly I needed to learn how to play the banjo. At the time, I had been taking guitar lessons for two years. Inspired by bands like Blink-182 and Green Day, I asked my parents for an electric guitar for a combined birthday and Christmas present. I got a classical Spanish guitar instead. I suspected they feared the loud noises I hoped to produce. But they did lovingly and patiently take me to guitar stores around Bogotá most weekends so I could play as many electric guitars as my heart desired.

I remember the confused looks from the vendors as I asked around town for a banjo. There were no stores, luthiers, or players selling them in Colombia at the time, as far as I could tell. It’s still very hard to buy one today. But as the years passed, I became hesitant to get a banjo, wondering if the music I play should reflect where I come from and who I am. No one my age cared about the banjo. I only saw and heard it on the albums of bluegrass or country musicians from the United States. It seemed to be particular to a unique place and culture, and not one that I could easily participate in. Learning to play it would be pretending to be something I was not; I had no reason to care about the traditional music from the Appalachians. If I wanted to learn a folk instrument, it might as well be one from Colombia or South America. I slowly abandoned my desire to play one.

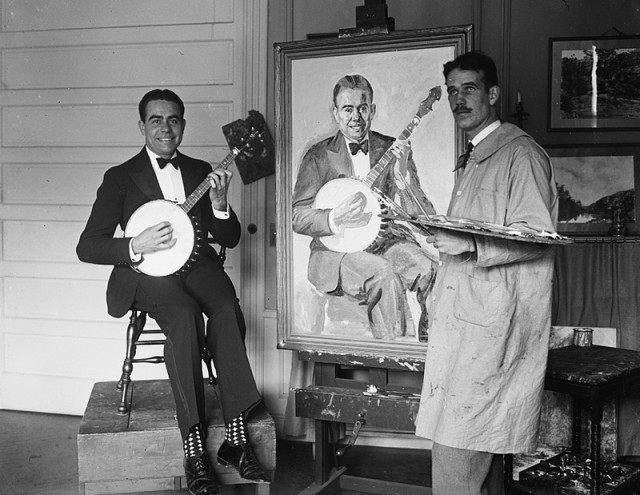

Artist painting man with banjo, c. 1924. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. [Library of Congress]

In 2008, my brother and I visited New York and had the opportunity to attend a free performance by the banjo virtuoso Béla Fleck at SummerStage in Central Park. That evening, he was promoting the documentary Throw Down Your Heart, a film about his musical journey with the banjo in Africa. In the movie, he explains that the instrument “has been associated so much with white southern stereotypes, and a lot of people in the United States don’t realize that the banjo is an African instrument.”

I was stunned. Why had I never heard of any African banjo players?

For years, I kept that information as a fun fact. But recently, I had been thinking about getting a banjo again. Before making any purchase, I decided to do some research, starting with a collection edited by the music scholar and musician Robert B. Winans. It is true that for the second half of the 20th century the banjo was mostly used by folk musicians from the Appalachian region in the United States. But its journey across the oceans and across cultures make the history of this instrument much more complicated and interesting than I initially assumed.

I learned that banjos have been played in Latin America for at least a century, perhaps first coming to the region with jazz musicians. In 1920, the first jazz band in Colombia, the Jazz Band Lorduy from Cartagena, featured a banjo player. The music was so new at the time, that the band had to import most of its instruments by steamboat.

I also found an imaginary 1921 interview with a pianola conducted by Mexican journalist José Luis Velasco. He reports: “Nowadays … girls are fascinated by the impertinent mumble of American jazz. The banjo and drums are as indispensable now as the violin and cello used to be … That music is noise, or rather, a torrent of noises.”

For years, I have worked on learning to play plucked string instruments. My current instrument collection includes several guitars, two ukuleles, a fretless bass, and a mandolin. As a player, it can be easy to assume that these instruments are finished products, not artifacts of ongoing historical processes that continue to generate new forms and playing styles. Learning about these changes has been illuminating. One aspect of this history that’s been especially interesting to me concerns the use of frets.

Frets are thin strips on the neck (or fretboard) of a stringed instrument that help the player play the “right” notes (most music around the world is based on 12 possible intervals or notes). Fretless instruments (like violins) do not have these strips, allowing the player to play “in between” the notes. The earliest banjo-like lutes and banjos appear to have been fretted, but their closest cousins in Africa are fretless.

As far as I can tell, there are at least two contemporary African instruments that sort of look like a banjo: the akonting and the xalam. Both are roundish fretless plucked lutes that produce very different sounds than those produced by contemporary banjos. Fascinatingly, these instruments appear similar to a string instrument depicted in a 4,000-year-old Egyptian tomb, and to another one in a 5,000-year-old Akkadian cylinder seal.

Our shared understanding of the banjo’s history in the Caribbean is biased by the historical record, which amplifies the point of view of those with enough power to be able to write about their experiences in the 16th and 17th centuries. Almost all are European authors describing their first contact with new cultures and languages. Much is missing, and there is plenty of room for misunderstandings. One of the earliest written descriptions of what today we could call a banjo comes from the 16th century. In the Colombian slave market and port city of Cartagena, the Spanish Jesuit monk Alonso de Sandoval wrote that some West Africans “play instruments similar to our Spanish-style guitars but made of rough sheepskin.” Rough sheepskin is the material used to make several drums in Africa, so it’s possible he was referring to an instrument with a long neck and a circle-like shape with a leather body, just like a banjo.

The banjo is not the only instrument introduced by enslaved Africans that continued to evolve in the Americas. Many types of drums — such the bongos in Cuba, the candombe drum in Uruguay, and jawbones throughout the Caribbean — were developed by enslaved Africans and their descendants. There are also many marimbas from Mexico and Costa Rica to Ecuador, all of which descend from the African balafon (a wooden xylophone that uses gourds for resonation).

In Colombia’s Pacific region, the marimba de chonta or el piano de la selva (the piano of the jungle) is made with wood from Astrocaryum standleyanum, a native palm that gives the instrument its unique sound, reminiscent of water. One of the most beloved songs played with this instrument is called Kilele. Many musicians in Colombia claim the word means party and community. In Swahili, the word means peak or noise.

In the 17th century, more illustrations and descriptions of instruments similar to the banjo appeared throughout the Caribbean. They are described as lutes made of gourds, and have circle or oval decorated shapes, long wooden necks with carved patterns and some frets, and two or three strings.

In 1687, the Irish physician Hans Sloane set sail to Jamaica. Throughout his career, he collected more than 70,000 objects from all over the world, which became the founding collection of the British Museum. Among those items were two gourd banjos, which sadly have not survived. In his 1725 book A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, Saint Christophers, and Jamaica, he describes a performance by enslaved people working at the British plantations: “at nights, or on feast days they dance and sing. Their songs are all bawdy, and leading that way, they have several forts of instruments in imitation of lutes.”

By the 18th century, there were accounts from Suriname to Boston of similar instruments with many names, including banjar and banger. Most were made with dried gourd fruit and dried animal skin. These early banjos were similar to their African counterparts but also had tuning pegs and carved wooden necks, comparable to some European lutes that sailors introduced in the Caribbean a hundred years earlier. The instrument was changing and becoming something new, the product of the many mergers that occurred throughout the centuries, a syncretism that led to new cultures that still shape us.

Banjo, by William Esperance Boucher Jr., c. 1840. [The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

In 1781, Thomas Jefferson wrote of the people enslaved in Virginia: “The instrument proper to them is the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa, and which is the original of the guitar.” Jefferson is wrong about the instrument’s history — the Persian oud is the ancestor of the guitar. Still, his writings suggest that in 18th-century Virginia, the banjo was primarily used by enslaved people.

A few decades later, minstrel shows made the banjo into one of the most popular instruments in North America. Because of minstrelsy’s racist history, many people never learn how widespread and influential this form of performance was in the 19th century. “It’s a problematic period for us to look back on because we don’t have a good way to talk about race in this country,” said composer and multi-instrumentalist Rhiannon Giddens in a 2015 PBS documentary. Throughout her career, she has used historical research to perform African American music “with a modern light and without completely decontextualizing it.” The documentation of minstrel shows offers one of the only windows onto some of the African American music from this time.

The banjos from this era are known as minstrel banjos. They have a body structure like contemporary banjos but are made primarily of wood, have beautiful intricate designs, and are fretless. Giddens’ main instrument is a fretless banjo with nylon strings, inspired by 19th century banjos — though the head and tuning pegs look more like those of a classical guitar. In the song “Better Git Yer Learnin’” Giddens plays minstrel music on her banjo, though the lyrics are her own and tell the story of African American education in the decades following the Civil War, when many Black schools were vandalized and burned. Most recently, her banjo can be heard on Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter, bringing the instrument’s unique history to new audiences in a way that continues to transform its sound.

I have been lucky enough to play historical replicas of the gourd and minstrel banjos in Jake’s Main Street Music in Beacon, New York. These instruments are quieter than modern banjos, with a warmer and more mellow tone. For someone who grew up playing fretted instruments, these banjos are much harder to play than their modern counterparts. The “in-between notes” played by a hand trained on fretted instruments sound very much like the wrong notes.

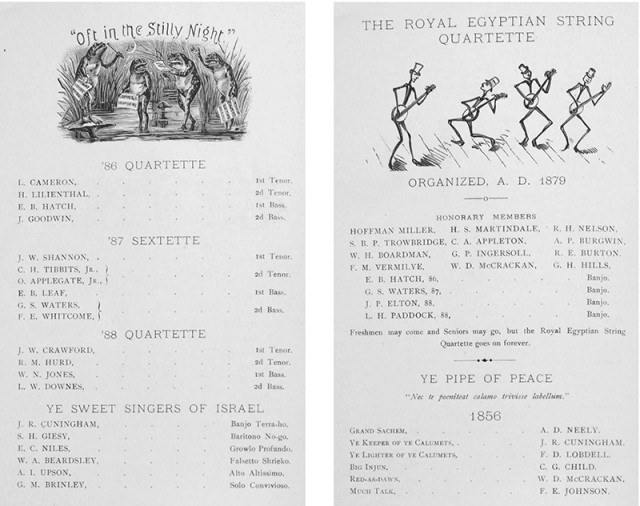

The success of minstrel shows led to the popularization of the banjo across the United States in the 19th century. The instrument was so fashionable that by the end of the century, elite schools like Trinity College had banjo orchestras. The university’s 1884 yearbook mentions performances by the Royal Egyptian String Quartette and the Ye Sweet Singers of Israel, whom a banjo player accompanied.

During the first half of the 20th century, the banjo had some notable changes. Among the most important are the reintroduction of frets and the adoption of steel strings, which made it sound louder. Early jazz orchestras adopted a banjo with four strings as a rhythmic instrument. This variation became so popular with Irish immigrants on the East Coast that it was introduced into Ireland. Since then, the banjo has been popular in Irish folk music.

By the middle of the 20th century, the banjo started to be replaced in orchestras by the electric guitar, my first musical love. It was much louder and cheaper to produce. As the years passed and popular music developed, the banjo disappeared from most popular music, surviving in bluegrass and folk music from the Appalachians and thus becoming associated mostly with, to use Belá Fleck’s phrasing, “white southern stereotypes.”

But this is reductive. Culture is not limited by time and geography; it is fluid and constantly changing as individuals interact with their social environments. As the decades pass, objects and art grow and change as new elements are incorporated, dropped, and transformed. Banjos, like the ukulele and the charango, have been used to create beautiful music, even though they came into this world through conquest, colonization, and violence in the Americas. I don’t think this should stop anyone from playing these instruments. But there is much to gain from learning their history. For example, the four-stringed banjo that was so popular with early jazz bands and Irish folk musicians also became a favorite of early Jamaican Mento musicians. Its island sound is so different from anything I previously associated with the instrument.

The Banjo Lesson, by Henry Ossawa Tanner, 1893. [Wikimedia Commons]

After much research and hesitation, I decided to get a Gold Tone fretless nylon string banjo. Fretless because it’s a challenge for me, and nylon strings because they sound and feel like home. (Nylon strings are also much quieter than steel strings, allowing me to stay in the good graces of my wife and neighbors.)

The banjo arrived the day after Christmas, and it was terrible. It had scratches, paint spilled over it, and damage to the fretboard and bridge. Worst of all, it did not have a good sound. I changed the strings and tried to improve its playability by making some minor adjustments. But after two weeks I had to return it. While talking with the seller about the problems with the instrument, he said I should not expect much from a “cheap instrument made in China.”

Half a millennium of history and the banjo can still reflect contemporary issues: cheap goods produced with low labor costs and low-quality materials.

I sent it back and got a refund. The search continues.