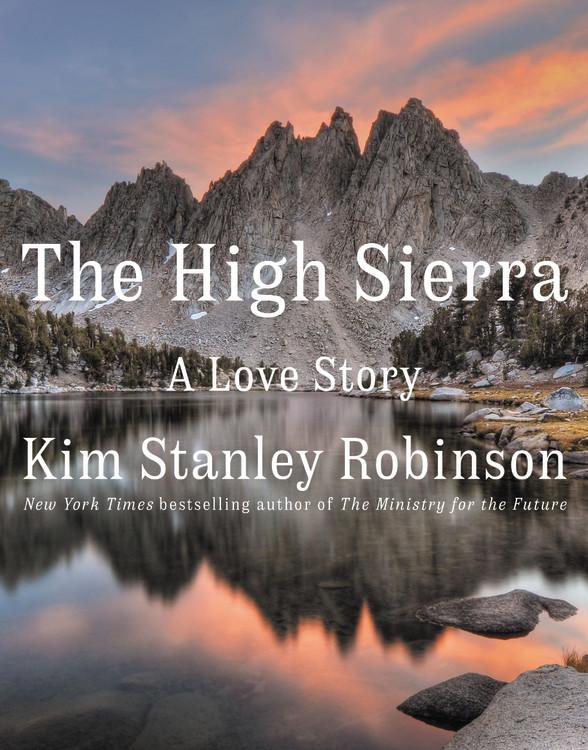

Hard on the heels of his latest science fiction novel, The Ministry for the Future — a blistering near-future vision of climate change — Kim Stanley Robinson has just published The High Sierra: A Love Story. The book is a captivating memoir laced with reflections on history, literature, geology, ecology, politics and psychogeography, all strung on the narrative thread of the author’s lifelong enchantment with rambling and scrambling in a wilderness without trails on a precarious planet spinning in space.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jon Christensen: How has the High Sierra influenced your science fiction?

Kim Stanley Robinson: I think it’s been formative, in a really deep sense. I was surprised how many of my texts have some analogue to the High Sierra. Right from the start, I can see when Hjalmar Nederland is wandering around Mars in Icehenge, it was a Sierra wander. And that kept happening. It was true in my Mars Trilogy. To terraform Mars is really cheating. Mars is basalt rather than granite. It’s poisonous rather than healthy. So, turning Mars into the High Sierras required something like a 2,000-page novel to make it even slightly plausible. I like it when my novels find their way to get in a big walk. It’s also a gesture toward Ursula K. Le Guin. In The Left Hand of Darkness, when Genly Ai and Estraven have to make a long trek across the glacier, that’s a brilliant piece of writing, and it has always inspired me.

JC: Has the process worked the other way around? Has your science fiction influenced how you experience the High Sierra?

KSR: When you’re hiking in the High Sierra, you’re high enough on this planet that you can look down into the Central Valley and down into the Owens Valley and think, “Look, you’re on a planet here.” This is a kind of a science fiction moment. It leads to other ideas. Like, what is the future of wilderness? Is there wilderness in the Anthropocene? And what are we going to do with this planet in the future? And then I’m also thinking to the deep past. What about the first people that arrived here? Somewhere between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago, humans were wandering these spaces, and they had backpacking kits that were not dissimilar to ours. They were using leather and wood and other natural materials to create light stuff that they could carry on their backs and be comfortable at the end of the day. When I’m up there hiking, my literary imagination, a historical imagination, is definitely fired up.

JC: What has changed in the High Sierra in your lifetime?

KSR: The main thing is that climate change has hit the Sierra. Fires mean that it’s often smoky up there, and the lower reaches have burned. And the glaciers are going, going, gone. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. I went up to the head of Deadman Canyon, where there had been seven glaciers, and now there’s one. And it’s teeny. It’ll be gone in three, four years. In the Sierras, everything is happening faster than we thought it would. You know, I was hoping I would die before this happened, and it would be someone else’s problem. But, no, it’ll be something that I’ll see on every trip for the rest of my life.

JC: And how are you feeling about the future of the Sierra Nevada?

KSR: I’ve been pondering that a lot. I think it’s a practice honed by the writing of science fiction. This is where we are, this is the trajectory we’re on, so let’s extrapolate. The Sierra is part of the 30-by-30 plan for California, keeping 30% of California wild by the year 2030. And they’re thinking of 50-by-50 to follow. The Sierras will be very important for that. Tree-ring data are very clear that there have been stupendous droughts in the American West, and we may be entering another one. That doesn’t mean that the Sierras are going to die off and be just dead rock. There are extremophiles up there. The life forms up there are used to desiccation, and then being under snow. And being so high and so close to the Pacific, they’re going to get some precipitation. Maybe it’ll be really irregular; maybe the Arizona monsoon coming up from the Gulf of California in July. But it won’t turn into one of these utterly lunar landscapes that you see some places, including other places in the American West. It will always be a little greener, a little more varied, a little more Sierra-like. That’s what I’m seeing as I try to run it forward. It’ll be hurt, damaged. It will change. But it won’t be dead. That’s a small comfort.

JC: You were very involved with naming Mount Thoreau recently. And your book takes on the debate about changing the names of some of the Sierra peaks named after racists and eugenicists. What is your guiding philosophy for naming the landscape?

KSR: I think it’s OK to name peaks after humans as a gesture of honoring them and what they stood for. But almost all the Sierra names came from the period between the Civil War and World War II. And they kind of blew it. The whole ethos at that time was about the great men of history. For one thing, it was intensely male. For another, they were business leaders. Stanford has two; there are two Mount Stanfords in the Sierra Nevada. So, these names, they’re crap. And if there’s the equivalent of a Confederate monument up there, which there is, let’s take it off. These magnificent peaks should have better names. Native American names should come back where we know them.

JC: One name you strongly believe should stay on the landscape is John Muir. Why do you think Muir needs defending now?

KSR: I do feel like his defense attorney. And, of course, he was not perfect. No one is perfect. I’m also trying to interrogate my own feelings now and realizing that I’m partly interested in questions of historiography, like, how do we judge people out of the past? And what’s the psychological motivation for judging historical figures for doing good or bad? Is it part of judging ourselves? I think it must be. So then it gets even more interesting. I am interested in Muir. I’ve read all of his writings, including his unpublished work in the archives. Muir has gotten a bad rap. Out of, I would guess, 3,000 to 4,000 published pages, there are, indeed, at least three or four pages of nasty comments about Native American individuals. Muir did not put it together that he was looking at a devastated refugee population. He was looking at prisoners. That was stupid on Muir’s part. And he had prejudices, that’s true. But actually, he was a huge admirer of Native American cultures.

JC: What do you think Muir still has to offer us — now, and in the future. Why shouldn’t we just bury him for good?

KSR: For Native Americans, Muir is symbolic of European settler colonial appropriation of Native lands. So we have white settler colonialism, and the incredible repressed guilt of the suppression and near extermination of the Native American population in this land. How, then, do you pay attention to this land? Like the Wes Jackson book Becoming Native to This Place, how do you do it? It’s really a religious question, in a way — the transcendentalist idea that nature is a sacred space, that God is imminent, that you can transcend by paying close attention to nature. As a powerful public intellectual of his time, Muir was a crucial figure in that. He was also an early reader of Thoreau. He read Walden when he was young. He read all 20 volumes of Thoreau’s complete works. To California Native Americans, Muir stands for appropriation of their ancestral lands, even though, compared to the military people with guns that actually killed them and drove them off, he was just some hippie figure wandering around up there going, “This place is beautiful!” But also, history is not determinative. In terms of its guidance to us, for what to do now, it’s extremely ambiguous. You can take what you want out of it.

JC: You’re not a big fan of the John Muir Trail, though, or bagging peaks. You prefer going off trail, scrambling over unnamed passes and rambling through high basins without trails. It seems to be almost a philosophy. Why?

KSR: Well, it’s beautiful. And you can do it. The Sierra is a giant eroded plateau. So, unlike certain other mountain ranges in the world, like the Swiss Alps, you can ramble without getting into immediate danger and without having to climb vertically. The John Muir Trail gets 90% of the traffic in the Sierra now. There is a lot of wilderness with no trails and very few names. When you’re rambling and scrambling, you get off trail, but you’re not putting your life at risk. The problems are solvable with some intense cognitive and physical effort. And you can get a little thrill of nervousness, like, oh gosh, I better not fall here. But even if you did fall, you aren’t going to kill yourself at the bottom of that fall, which is exactly what I don’t like about climbing. So the rambling and scrambling is quite a beautiful activity. To be quite honest, I’m playing a game up there. It’s all for the fun of it. I’m like a 5-year-old on a jungle gym. And it’s just a spectacularly great jungle gym.

Jon Christensen teaches and does research in the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and the Luskin Center for Innovation at UCLA, where he is a founder of the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline "We’re on a planet here!"

This article first appeared on High Country News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.