The U.S. declassification effort began under persistent pressure from Argentine human rights groups founded to uncover the atrocities of the dictatorship – a period I have spent my academic career studying.

Argentine democracy was interrupted by military coups six times in the 20th century.

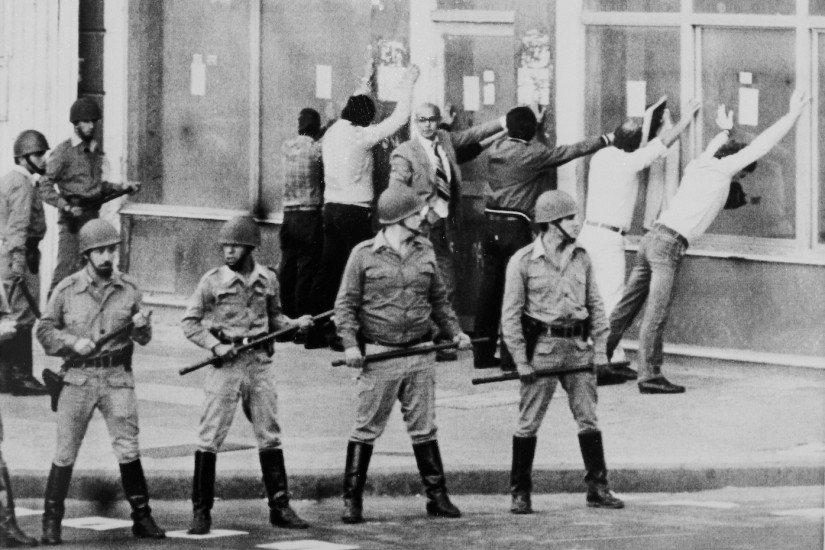

The declassified documents outline what happened after the last coup, staged in 1976 by Gen. Jorge Rafael Videla. It gave way to the cruelest, most repressive and violent eight years of Argentina’s history.

In August 2000 representatives from Argentina’s Center for Legal and Social Studies and the original Grandmothers and Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo – a human rights group that locates the lost children of the dictatorship, which has since splintered into several factions – met with U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

That encounter led to the declassification of 4,700 State Department documents in 2002. Those documents included U.S. diplomatic cables, memoranda, reports and meeting notes related to the Argentine dictatorship, and revealed clear U.S. involvement in the junta’s “dirty war.”

Now, Argentina has the military and intelligence archives behind these operations, too.

The declassified documents show that U.S. intervention in Latin Americawent well beyond giving “a little encouragement” to Latin American military regimes, as Secretary of State Henry Kissinger put it in 1976.

Argentina was the operations center for Plan Condor, a U.S-organized alliance between the dictatorships of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay, created in 1975 and operational until around 1980.

Fearing the spread of communism across the Americas, the Ford administration offered these rightist military regimes everything from counterinsurgency training and financial assistance to intelligence briefings.

With U.S. support, Argentina’s junta kidnapped leftists, dissidents, union leaders and anyone who looked remotely like a threat. They tortured detainees, and then threw them alive and conscious out of airplanes into the River Plate, near Buenos Aires, or dumped their bodies in mass graves.

Pregnant women were killed after giving birth, their babies adopted by the families of childless generals. Neighbors under police surveillance informed on other neighbors to appease the junta, then were abducted and tortured anyway.

The U.S. eventually grew uncomfortable with the activities of its Argentine allies.

In 1976 Robert C. Hill, U.S. ambassador to Argentina, reported to Washington that the number of people detained by the junta must “run into the thousands” and, with Kissinger’s knowledge, confronted the Argentine government about its human rights abuses.