Did the movies ever matter? They did to Ronald Reagan.

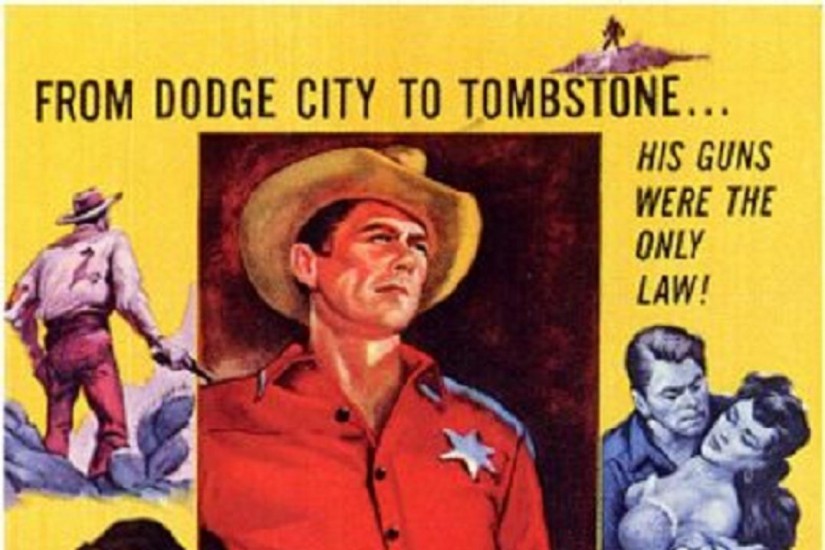

Reagan was made by the movies—not just his career but his mentalité was made in Hollywood. As much as he had been a movie actor, Reagan was a fan—a true believer in what he saw, or imagined, on the screen.

My takeaway from several days of research in the Reagan Library—a Magic Kingdom shrine set on a Simi Valley hilltop—was the degree to which Ronald and Nancy Reagan regarded themselves as senior members of the Hollywood community. The presidency was fine but movie stardom was the supreme gig.

Reagan would tell many, Warren Beatty among them, that he couldn’t understand how anyone could be president without having first been an actor. A politician who built a career on a professional image, Reagan knew how to take direction and hit his marks. He intuitively grasped how a president (or a good Joe or action hero) is supposed to present himself.

It was second nature for President Reagan to project himself into current movies, to quote one-liners from Dirty Harry (1971) and Back to the Future (1985), appropriate tropes from George Lucas, and cite Rambo (1982–1988). The morning after screening E.T. (1982) in the White House, he had himself briefed on the US Space Program.

Movies were real. Reagan did not doubt that there had been a Kremlin-directed plot to take over Hollywood and retroactively cast himself as the hero who prevented it. The movies of the 1940s were never far from his mind, whether borrowing lines from State of the Union (1948), reliving scenes from Wing and a Prayer (1944), imagining his pet dog Rex was the subject of Lassie Come Home (1943) or that, as he once told Israeli leaders, his Culver City-based film corps had liberated a concentration camp.

As president, Reagan enjoyed revisiting his old movies. “It’s like seeing a younger son I never knew I had,” he liked to say of watching himself as George Gipp, the gallant, doomed college halfback in Knute Rockne, All American (1940). Reagan had a special fondness for Kings Row (1942), the small-town exposé, which not only provided him with his favorite dramatic role but also the title for his ghostwritten 1965 memoir, Where’s the Rest of Me?