Emily Bingham’s new book offers a powerful story of how, exactly, we fool ourselves into thinking the past is past.

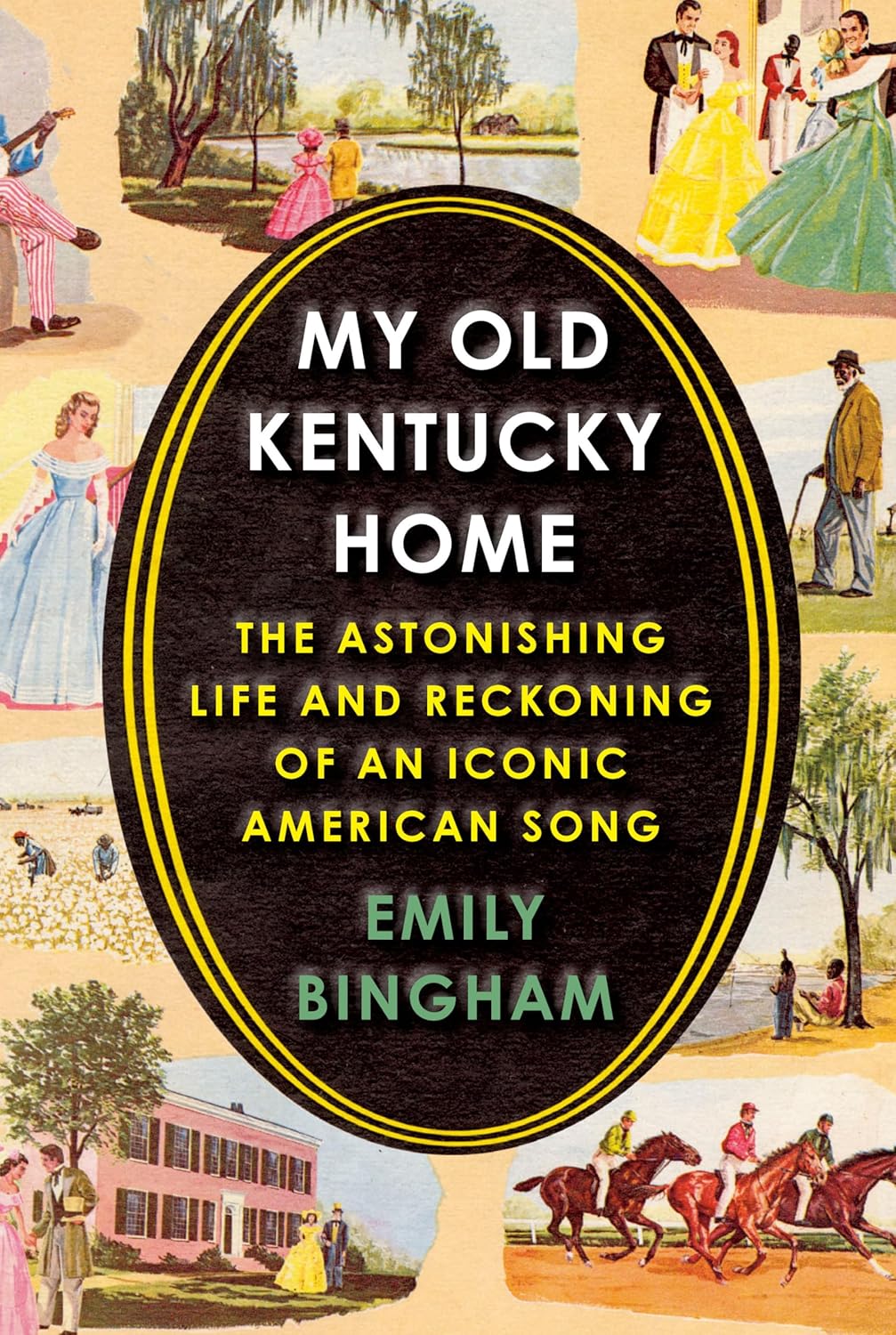

In “My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song,” Bingham — a historian and member of an influential Louisville newspaper family — takes readers through the song’s erased histories, as well as the Bingham family’s own. It is a chronicle of how generations — of not just Kentuckians but people across the country and in many parts of the globe — have sung out bucolic longing, not for a home but for an enslaver’s plantation: “We will sing one song for the old Kentucky home/For the old Kentucky home, far away.”

Bingham begins with Stephen Foster, who is unironically known as “the father of American music.” Foster, it turns out, came from a family of Pittsburgh Confederate defenders. They were a family who pretended to be of means when they weren’t. They needed Stephen to earn. He proved he could when he turned to writing minstrelsy, that racist and profit-generating variety show.

Today’s crowds who enjoy the song “My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!” — the state song of Kentucky and the hallmark of the Kentucky Derby — often fail to realize that Foster first wrote it in buffooning dialect. Bingham argues that this early version, which was called “Poor Uncle Tom, Good Night!,” adapted and bent the story by Harriet Beecher Stowe. In borrowing the novel’s celebrity while also changing the story’s terms, Foster would give his minstrel show’s viewers an unsavable Tom, who in the song dies wishing he could return to the plantation.

But Foster thought to make even better money, realizing that if he recast the lyrics without a named character, and in General American English dialect, he could also reach the parlor demographic, those middle-class piano-playing White women who were buying up all the sheet music. He could write a song that worked for different audiences, depending on who was singing. And why.

That’s just this book’s first chapter. Bingham has given us an account that is both riveting and thorough, taking us across a century of spinout marketing campaigns, protests and versions that emerged from Foster’s lyrics. Shirley Temple, Colonel Sanders, the country of Japan, Henrietta Vinton Davis, J.K. Lilly, Marian Anderson, Richard M. Nixon, the 31W Highway, “Mad Men” — and yes, the Kentucky Derby — are all summoned. Before Bingham’s done, she will argue with powerful momentum that the song “is a spy hole into one of America’s deftest and most destructive creations: the ‘singing enslaved person’ whose song assured hearers that the plantation was happy and a place where Black people belong.”