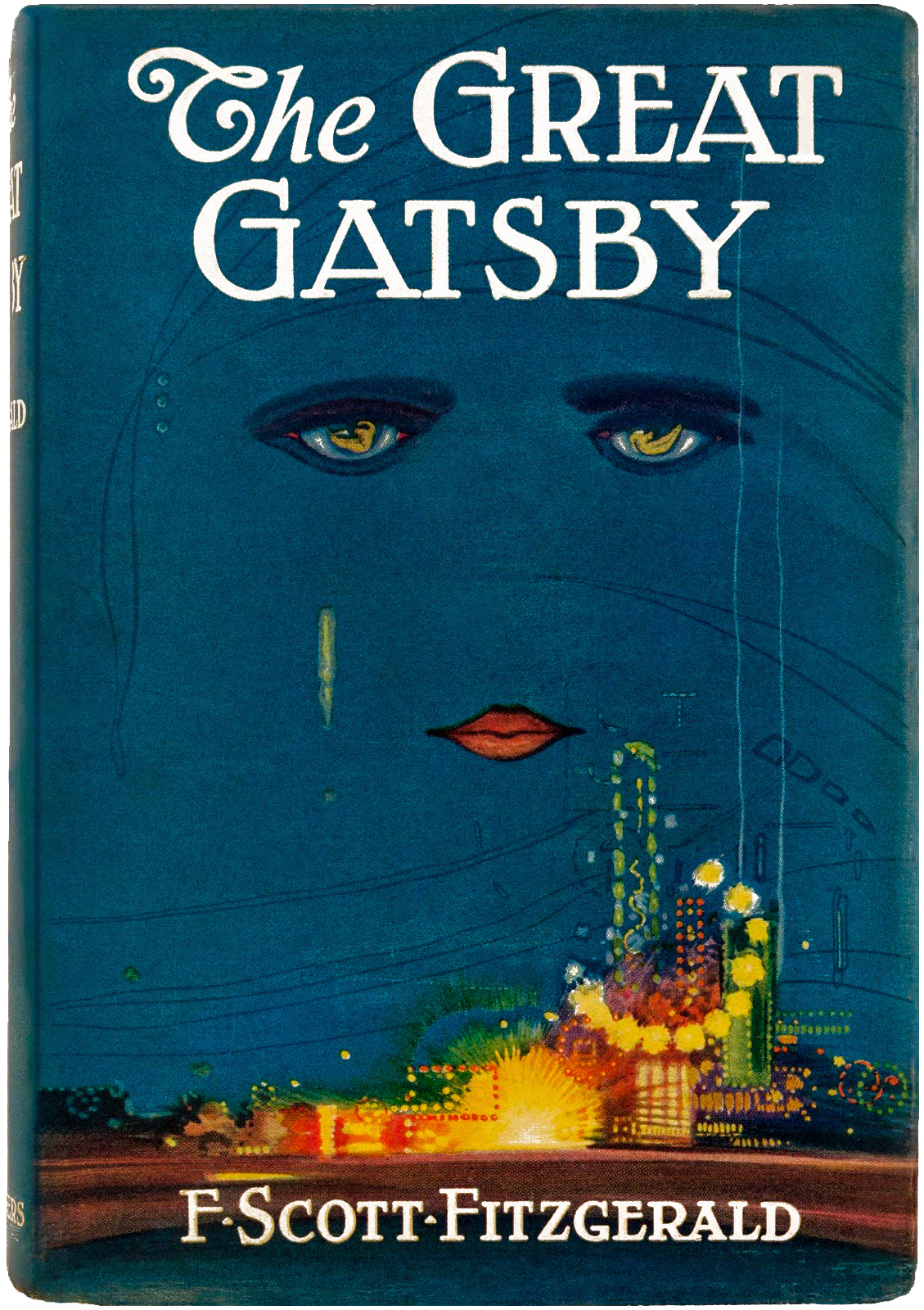

Under the Red White and Blue is about everything they left out of The Great Gatsby when you studied it in school. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel resonates like no other American fiction of the twentieth century, “for generations exerting a gravitational pull so insistent that it can seem to have colonized the imagination both of its own country and of people imagining that country from somewhere else.”

The title Under the Red White and Blue is among the ones Fitzgerald wanted for Gatsby, his greatest work of fiction; luckily his editor, Maxwell Perkins, pointed him in a different direction. Marcus follows the DNA strands emanating from the most celebrated American novel of the twentieth century. I use “celebrated” as a catch-all for popular, critically acclaimed, most widely discussed, and, inevitably, the Great American Novel, though Marcus is unconcerned with anointing Gatsby any of these honorary titles.

It is the Great American Novel, though when it was published many were too close to Gatsby’s themes to understand that it would outlive other much-heralded books by prominent authors the mid-1920s, such as Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith, John Dos Passos Manhattan Transfer, Faulkner’s first novel, Soldier’s Pay, and Hemingway’s first story collection, In Our Time.

Was Hemingway, whose best-known novels would be set outside the U.S., too jealous to acknowledge a novel that caught the heartbeat of an America he never understood? It was another expatriate who instantly perceived Gatsby’s greatness: T.S. Eliot wrote to Fitzgerald in 1925 that The Great Gatsby was “the first step that American fiction had taken since Henry James.”

Marcus says Fitzgerald “was seeing, or trying to see, the whole arc of American history, keeping it in his mind’s eye like a map tacked to the wall in front of his desk.” Gatsby is read as a kind of secret history of America, one that “absorbed the ferment of its time.” Fitzgerald “took into his book the action of the previous five years [of the twenties] – the fortunes, crimes, and songs -- and with such an acute sense of what the time wanted and what it feared that he was able to create an atmosphere in which the action of the next five years – the speculation, the panic, and the songs – had already taken place.” The era “was a bacchanal that left every question worth asking hanging in the air.”