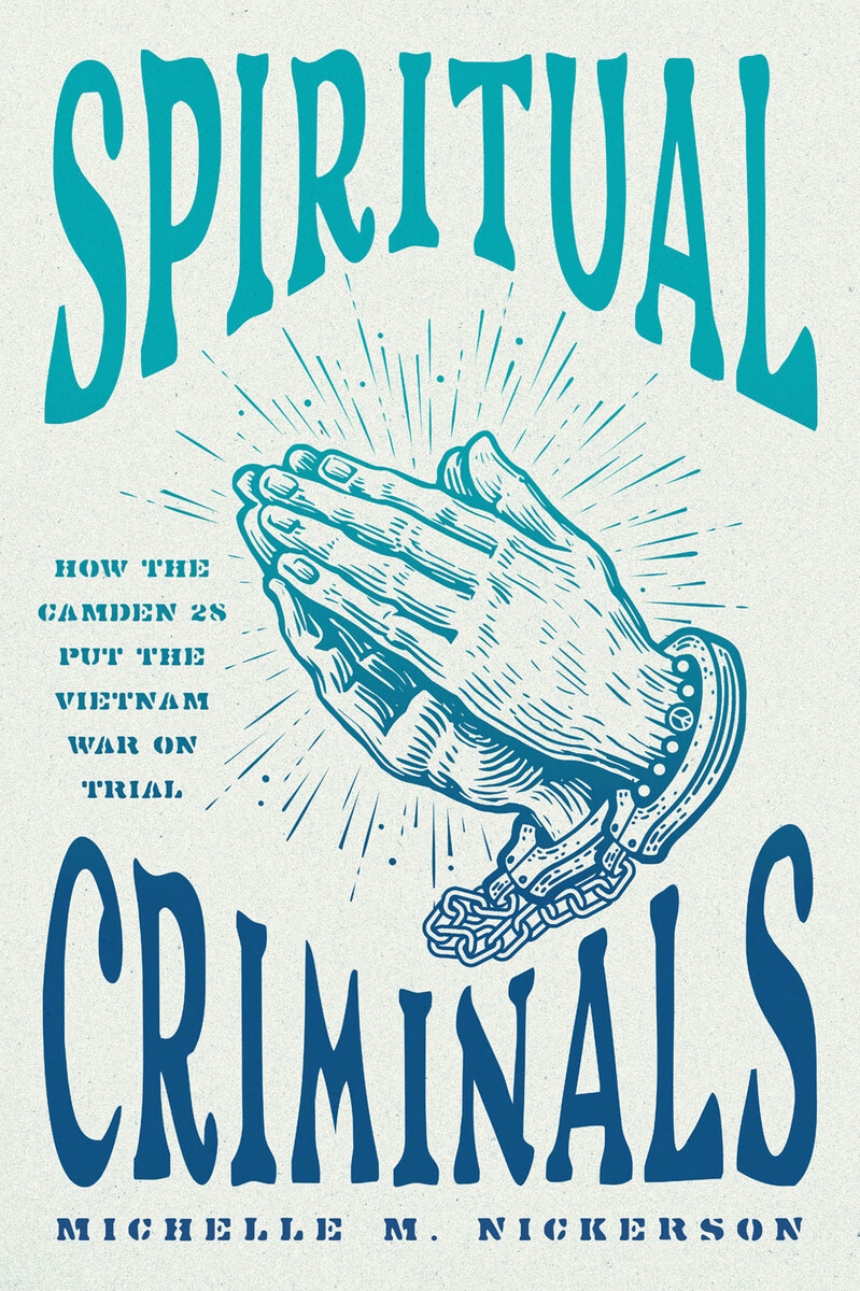

Michelle M. Nickerson’s recent book, Spiritual Criminals, offers a window into the Catholic Resistance through a lesser-known episode during the movement’s twilight years—the August 1971 raid of a draft-board office in Camden, New Jersey, and the subsequent Camden 28 trial that took place in the spring of 1973. As in most antiwar trials of the time, the defendants openly embraced their actions during oral arguments; but unlike in most antiwar Vietnam-era trials, they won full acquittals on all counts. The story is extraordinary on many fronts—for example, one of the defendants’ saving graces came in the form of the testimony of Bob Hardy, a raider-turned-FBI-informant who seemed to intentionally weaken the prosecution’s case, perhaps as repentance for his betrayal.

Nickerson’s definitive account of this underappreciated episode in antiwar history also complicates the standard historiography of the Catholic antiwar movement. But beyond its scholarly merit, it’s an urgent, timely book, particularly as millions of people across the country are grappling with how to reckon with—and resist—contemporary war-making. The teachings of the Catholic Resistance, we learn, are more relevant than ever.

Spiritual Criminals joins a burgeoning canon of excellent revisionist examinations of mid-century Catholic political and social life, an area that provides seemingly limitless points of entry for scholars. It’s among the most dynamic periods of American history. The world sifted through the wreckage wrought by World War II; the United States ascended to the status of global hegemon; billions of colonized people marched on a path to freedom from foreign rule; and the institutional Church embarked on its most consequential doctrinal reform in centuries, ushering in changes that would affect the daily lives of hundreds of millions of its adherents.

Nickerson’s work sits well alongside other recent books tracing the relationship between Catholicism and postwar politics, including Peter Cajka’s Follow Your Conscience, D. G. Hart’s American Catholic, and a phenomenal new collection of Philip Berrigan’s writings published last spring, edited by Brad Wolf. This uptick in scholarly interest must be in part due to the past decade of domestic political strife. Until recently, the fusionist consensus holding the conservative political coalition together seemed unbreakable. Marrying small-market economics with conservative social commitments, it seemed so steady, in fact, that received political wisdom had begun to espouse an immutable harmony between religiosity and conservative politics.