Have you heard about that time in the late sixties when three student protesters were shot dead by state troopers? No, it wasn’t Kent State, in May 1970, when four white students were killed by the Ohio National Guard. Nor was it Jackson State, eleven days later, when two black students were killed by Mississippi police. This was in Orangeburg, South Carolina, two years earlier, and it was in many respects a watershed moment: it marked the first time in U.S. history that students were killed by police on their own campus, according to sociologists Charles Gallagher and Cameron Lippard, and it presaged the ruthlessness with which the state would repress the rising Black Power movement in the months and years to follow. Yet, in the words of a 2008 New York Times article, the incident “never pierced the nation’s collective memory of the 1960s.” Amid so many tributes to the events of 1968, we would do well to remember it today.

On February 8, 1968, in the college town of Orangeburg, state troopers and police shot into a crowd of African-American activists, killing three and wounding twenty-eight more, in what came to be known as the Orangeburg massacre. The murders of Samuel Hammond, Henry Smith, and Delano Middleton at the hands of the police was a stark reminder of the limits of the civil rights movement’s gains. It also forced a meditation on how far the South—and the rest of the nation—still had to go in terms of both implementing the letter of the law on civil rights and respecting newfound racial pride among African Americans.

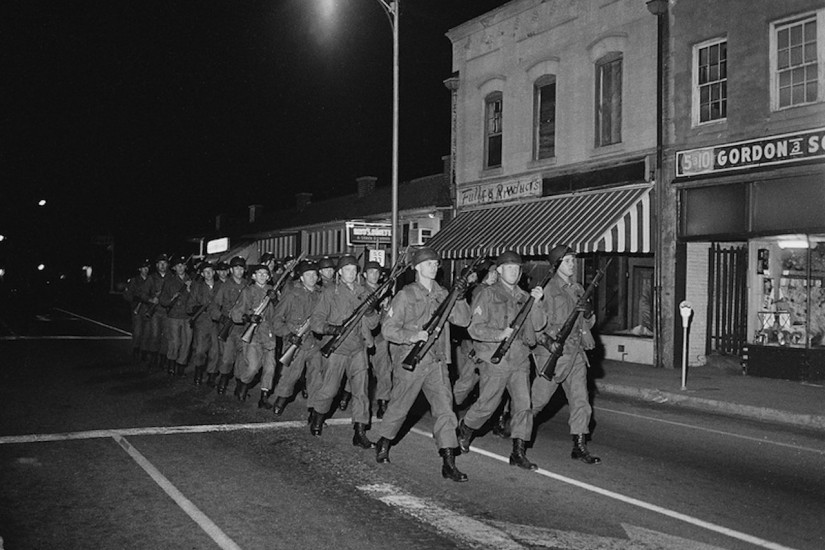

The incident’s origins traced back to the All-Star Bowling Lane, one of only a few remaining segregated institutions near the campus of the historically black South Carolina State College (now university) in Orangeburg. After the owner refused to recognize community members’ demands to desegregate the bowling alley, students took the lead in protesting the establishment. On the evening of February 5, a group staged a sit-in at the bowling alley’s lunch counter. The police were called in, but no one was arrested. When the students returned the next night, however, the police were waiting along with a contingent of highway patrolmen, blocking the entrance to the bowling alley. Fifteen students were arrested after they rushed the door and refused to leave. Before long, the protest escalated. A crowd of at least 200 formed, and tensions flared when a fire truck appeared on the scene, stoking fears that fire hoses might be used to disperse the crowd. When a window was broken, police charged and began beating the students brutally with batons. Returning to campus, some students, already bloodied, broke more windows in outrage.