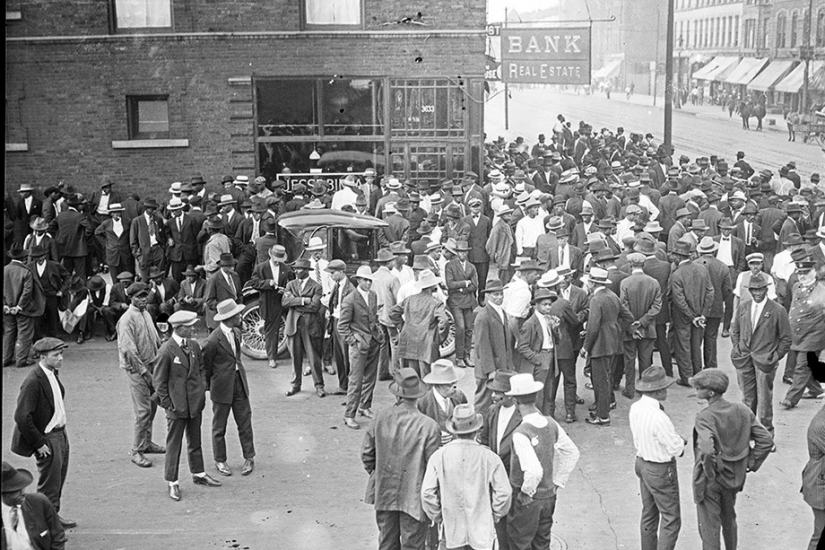

In his new book, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back, David F. Krugler, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Platteville, looks at the actions of people like Jones and Davis, who resisted white incursions against the black community through the press, the courts, and armed defensive action. The year 1919 was a notable one for racial violence, with major episodes of unrest in Chicago; Washington; and Elaine, Arkansas, and many smaller clashes in both the North and the South. (James Weldon Johnson, then the field secretary of the NAACP, called this time of violence the “Red Summer.”) White mobs killed 77 black Americans, including 11 demobilized servicemen (according to the NAACP’s magazine, the Crisis). The property damage to black businesses and homes—attacks on which betrayed white anxiety over new levels of black prosperity and social power—was immense.

The history of black responses to the violence of 1919—which ranged from the use of a single weapon against a home invader, to the organization of defensive posses like Davis’ that were meant to protect potential victims of lynching, to the deployment of groups of men who patrolled city streets during unrest—makes it clear that armed self-defense, far from being an invention of Malcolm X and the Black Power movement, is a strategy with deep roots. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement, the story of nonviolence—a beautiful strategy with uncontestable moral force—has taken center stage. However the story of active self-defense against violence—a tradition that developed before, and then alongside, nonviolent resistance—is too often dismissed or simply ignored. Even before slavery had been outlawed, black Americans took up arms when their lives and livelihoods were threatened. Their experiences make the familiar history of marches and peaceful protest more complex. But the story of the civil rights struggle is incomplete without them.