Shannon Byrne pulls her black Honda Civic under low-hanging tree branches and, slightly askew, into a parking space near St. Michael & All Angels church. The building is about a quarter mile from the west gate of Georgia's Stone Mountain Park, but Byrne would much rather walk than pay the $40 annual parking fee. That price would be a bargain for someone like Byrne, who climbs the 825-foot-high granite dome almost daily, year-round—but she refuses to give a penny to the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, the entity that manages private funding for the state-owned land. She can't stomach the thought of her money being used to maintain a Confederate monument.

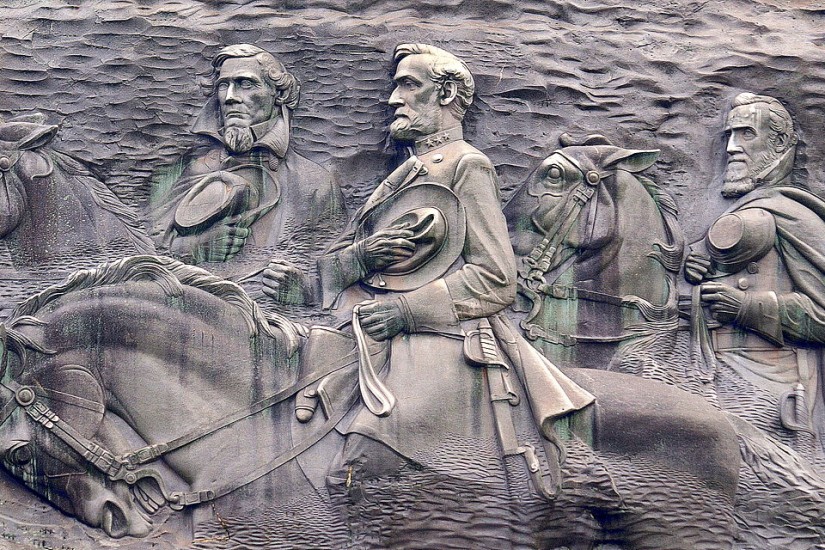

Byrne doesn't sneak through the park's gate. She glides defiantly past the booth attendant, who offers a nod of recognition but not a smile. Then she walks down Robert E. Lee Boulevard, past Confederate Hall—"Confeder-Hate Hall," she sneers. The columned antebellum-style mansion houses a theater playing the melodramatic 24-minute film The Battle for Georgia: A History of the Civil War in Georgiaand a museum that details the carving of the infamous 90-foot-tall bas-relief of Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson into the mountain's north side. She holds her nose as she passes the terrace where the four flags of the Confederate States of America flutter above the foot of the summit trail.

Then she exhales.

Before her is a park of towering pine and Georgia oak populated with climbers of all ages, nationalities, and ethnicities. Some are tourists, checking off a scenic stop on their itinerary; others are locals getting in a workout. Some are here to commune with nature; others are here for fellowship. All have one destination, one mile ahead. "I wonder if some of these people know what a powerful act it is just for them to be here," she says. "Reclaiming the mountain from a history of hate."