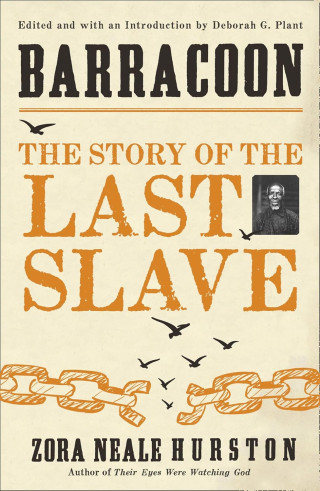

In “Descendant,” the present-day Black descendants of those enslaved on the Clotilda fight to preserve the stories of their ancestors in the face of historical erasure. The most well-known ancestor is Cudjo Lewis, who helped found Africatown, where many Clotilda descendants still live. In 1928, Zora Neale Hurston spoke to Cudjo for an oral history, which would later become the book “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo.’ ” The film is interspersed with excerpts from this interview, read by descendants in the places that Cudjo lived and worked. Publishers rejected Hurston’s manuscript, objecting to her choice to phonetically render his Black vernacular speech, a rich mix of Yoruba and English. The manuscript remained unpublished until 2018, the same year that Brown started shooting her film.

In “Barracoon,” Cudjo recounts the story of the Clotilda. It is often said that in the run-up to the Civil War a wealthy businessman named Timothy Meaher made a bet that he could bring a ship full of Africans to Mobile and not be caught. The federal government had outlawed the importation of human cargo some fifty years prior, and Meaher and his friends were eager to prove that they could flout national regulations, according to Sylviane Diouf, a leading historian of the Clotilda. Meaher bought a schooner for a voyage to Ouidah, in the kingdom of Dahomey, in modern-day Benin, where he funded the purchase of a hundred and ten young men and women. When the Africans arrived in Alabama, they were forced off the ship and made to hide in the swamplands. The schooner was burned and scuttled to destroy evidence of the voyage; Meaher would have faced the death penalty if discovered. The captives were enslaved and put to work locally or sent to plantations farther away. Five years later, at the end of the Civil War, these men and women gained their freedom, but Meaher refused to give them land. Instead, he and others sold many of them small parcels on which they founded Africatown, an autonomous community where they grew food, ran businesses, and taught the next generation their customs and languages. They built a cemetery that faced east, toward Africa. The Meaher family is still one of the biggest landowners in Mobile, and over the years they have leased their land to industrial plants that have polluted the land and contributed to a public-health crisis in the community, according to research done by the Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition. They have never apologized for the Clotilda voyage.