In October 1981, scholars, artists, and community residents gathered at UICC (University of Illinois at Chicago Circle) for a conference entitled “Art, Architecture and the Urban Neighborhood.” Perry R. Duis, a professor of urban history, praised the wave of community revolt that had swept through Pilsen: “Instead of a plan imposed entirely from outside the community, [Benito Juárez High School] was designed with the help of Pilsen residents.” Duis remarked on how residents carried out their own aesthetic vision: “The sloping walls reflect the Mexican architectural heritage, not aesthetic ideas imported from outside the neighborhood.” Moreover, “the high school project is also significant because it demonstrates one approach to the serious question of urban redevelopment and the rejuvenation of neighborhoods.”

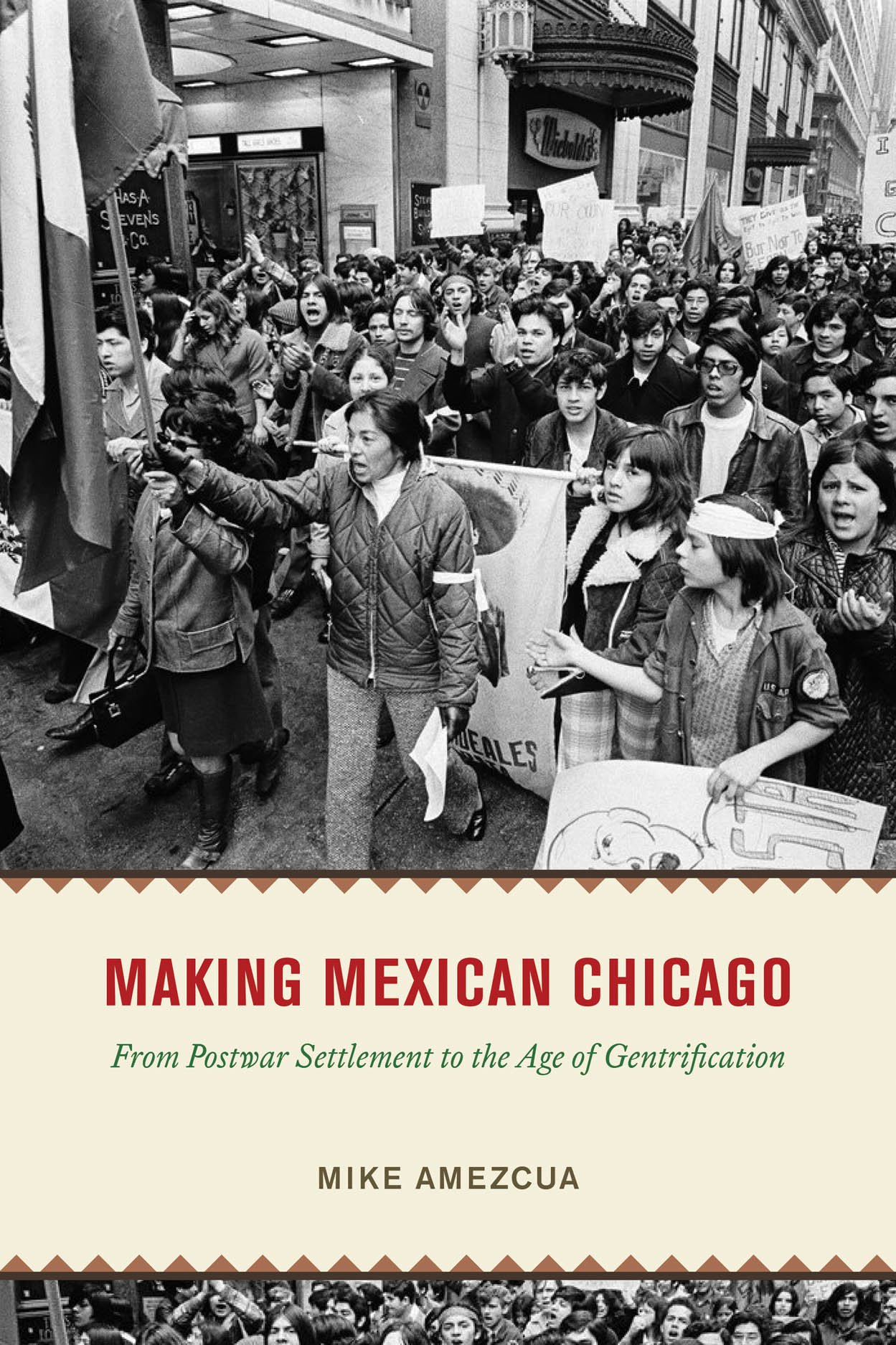

As Duis spoke about building an architecture of Latino empowerment, the United Neighborhood Organization (UNO) was setting out to build another movement. Looking to address not just Pilsen, but other Latino colonias, and the political and economic subjugation the very word implied, the community group mounted a campaign to address racial injustice and infrastructural inequality. At the start of the 1980s, plant closures, overcrowded and underfunded schools, and blighted housing conditions continued to grip Latino neighborhoods, while becoming the battleground sites on which Latinos sought to build neighborhood-based power. This new decade would be a period of significant grassroots political mobilization for Latinos themselves, driven by demographic growth, economic and structural neglect, and an inspired politics of self-determination.

When Richard J. Daley died in 1976, he left a political machine in place that could still control and undermine growing Latino political power. City hall continued his long tradition of redrawing district and ward boundaries to prevent Latino supermajorities from manifesting. But gerrymandering could not hide the fact that Latino settlement was widening on the heels of white depopulation. In the Southwest Side and the Bungalow Belt, from 1970 to 1980, population numbers dipped in most communities, with the exception of Pilsen, which saw a minor increase, and Little Village, which showed a significant boost from 62,895 in 1970 to 75,204 in 1980. Pilsen and Little Village were becoming denser during this decade, but Mexicans were also moving south of the river, in hopes of flipping formerly white neighborhoods to Mexican ones.

In the meantime, areas surrounding the Downtown Loop were turning over as well. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, the evisceration of the white tax base continued to guide city hall politics as boosters, planners, and bureaucrats pursued redevelopment schemes to flip valuable real estate in the central city, hoping to bring back suburbanites. In Pilsen, speculators of all stripes, from lawyers to slumlords to former city bureaucrats, seized on this moment to flip their properties and create “colonies” of their own to attract “urban pioneers” and “white homesteaders,” displacing poor and working-class Latinos in the process. Community organizations saw this as a project of cultural erasure and outright colonization.