Reading is good; rereading is better. I can’t say with certainty how many times—forty? fifty?—I’ve read James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” only that for more than thirty-five years I’ve been reading and teaching the story, each time with an undiminished sense of awe and appreciation for how Baldwin issues a prophetic warning about the outcome of racism while making deeply felt gestures of hope and reconciliation.

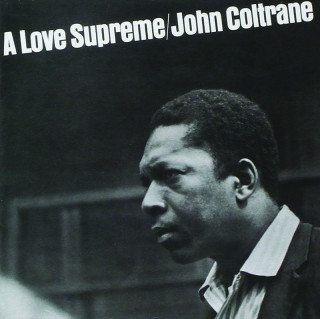

As the title indicates, the story moves on its music, specifically jazz. Whenever I read “Sonny’s Blues,” I think of John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme,” a long, prayerful piece that gives thanks for his recovery from heroin addiction and that percussively, sonorously refrains its title in praise of the Creator. Coltrane’s song dates from 1963, a few years after “Sonny’s Blues,” and both pieces take part in a shift occurring in race consciousness and the American psyche. “A Love Supreme” proceeds in four parts—a similar orchestration to “Sonny’s Blues,” which occurs in three acts with a denouement and begins with a song of denial:

I read about it in the paper, in the subway, on my way to work. I read it, and I couldn’t believe it, and I read it again. Then perhaps I just stared at it, at the newsprint spelling out his name, spelling out the story. . . .

It was not to be believed and I kept telling myself that . . .

The occasion of “Sonny’s Blues” is that a long-standing denial of a horribly painful truth has come home to the main character and can no longer be denied, though he tries. Having established this conflict, Baldwin promptly reveals the news: the narrator’s younger brother, Sonny, a jazz pianist, has been arrested for using and peddling heroin. From that moment, the story proceeds with forthcoming directness. What’s at stake is life and death.