The Lydian Monarch had been sighted from Fire Island and was expected in Jersey City that evening. Everybody in New York City was already buzzing about what was on board. It was March 28, 1884, and P. T. Barnum, the circus proprietor and showman, after great effort and expense, had brought the first “sacred white elephant” to America. An earlier attempt to buy a white elephant from Siam (Thailand) had ended in failure, but now Barnum’s agent, J. B. Gaylord, had successfully purchased an elephant named “Toung Taloung” — or “Gem of the Sky” — from King Thibaw of Burma. From Rangoon, Toung Taloung was brought by ship through the Suez Canal, and arrived in Liverpool, England on January 14. After several weeks at the London Zoological Gardens where it became something of a sensation in both the British and American press, the white elephant, its handlers, and Barnum’s agents eventually sailed for New York on March 8. When the Lydian Monarch arrived twenty days later, Barnum and his entourage rushed to New Jersey to meet Toung Taloung.

The following day, in a story titled “The Sacred Beast Here”, the New York Times offered a dramatic account of Barnum’s first encounter with his prized white elephant. “Of course we have all learned by this time,” Barnum told his retinue, “that there is no such thing as a really pure white elephant. This is a sacred animal, a technical white elephant, and as white as God makes ’em. A man can paint them white, but this is not one of that kind.” Although readers who had followed the coverage of Toung Taloung’s reception in London would indeed have learned that white elephants are not literally white, Barnum’s matter-of-fact statement belied the controversy that the color of white elephants had already engendered in the popular imagination. In 1884, Toung Taloung was the catalyst for a broader public debate about race and authenticity.

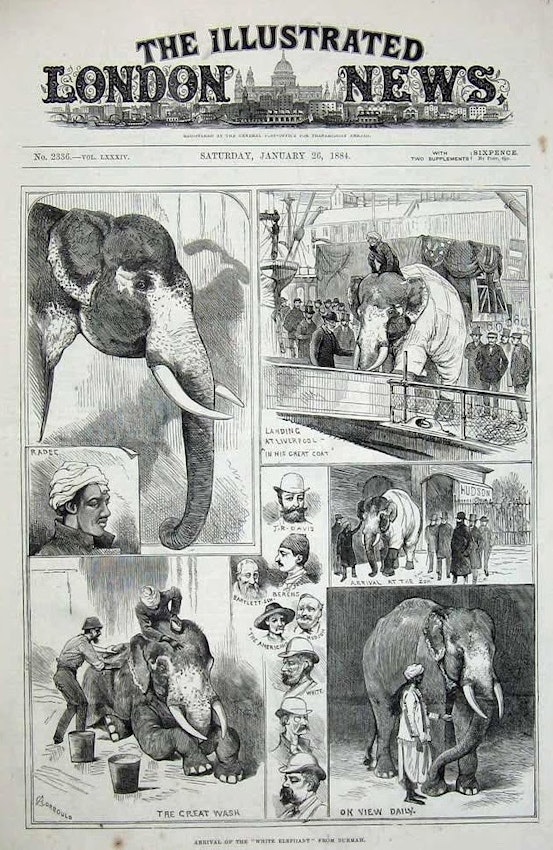

Front page of the Illustrated London News, January 26th 1884, celebrating the arrival of Toung Taloung to London —Source.

A few months after Toung Taloung arrived in New York, Frank Vincent Jr., author of the popular 1874 travelogue The Land of the White Elephant: Sights and Scenes in South-Eastern Asia, used explicitly racialized terminology to explain the color of white elephants to readers of the Manhattan. In an article titled “White Elephants”, Vincent writes,

It should always be remembered that the term white, as applied to elephants, must be received with qualification. In fact, the grains of salt must be numerous, for the white elephant is white only by contrast with those that are decidedly dark. A mulatto, for instance, is not absolutely white, but he is white compared with a full-blooded negro. The so-called white elephant is an occasional departure from the ordinary beast.

For Vincent, both the white elephant and biracial people share a kind of “qualified” whiteness that serves to distinguish them from “full-blooded” black bodies (Vincent refers to regular elephants as “black”), but stops short of aligning them with the kind of privileged white identity that Vincent himself possessed.