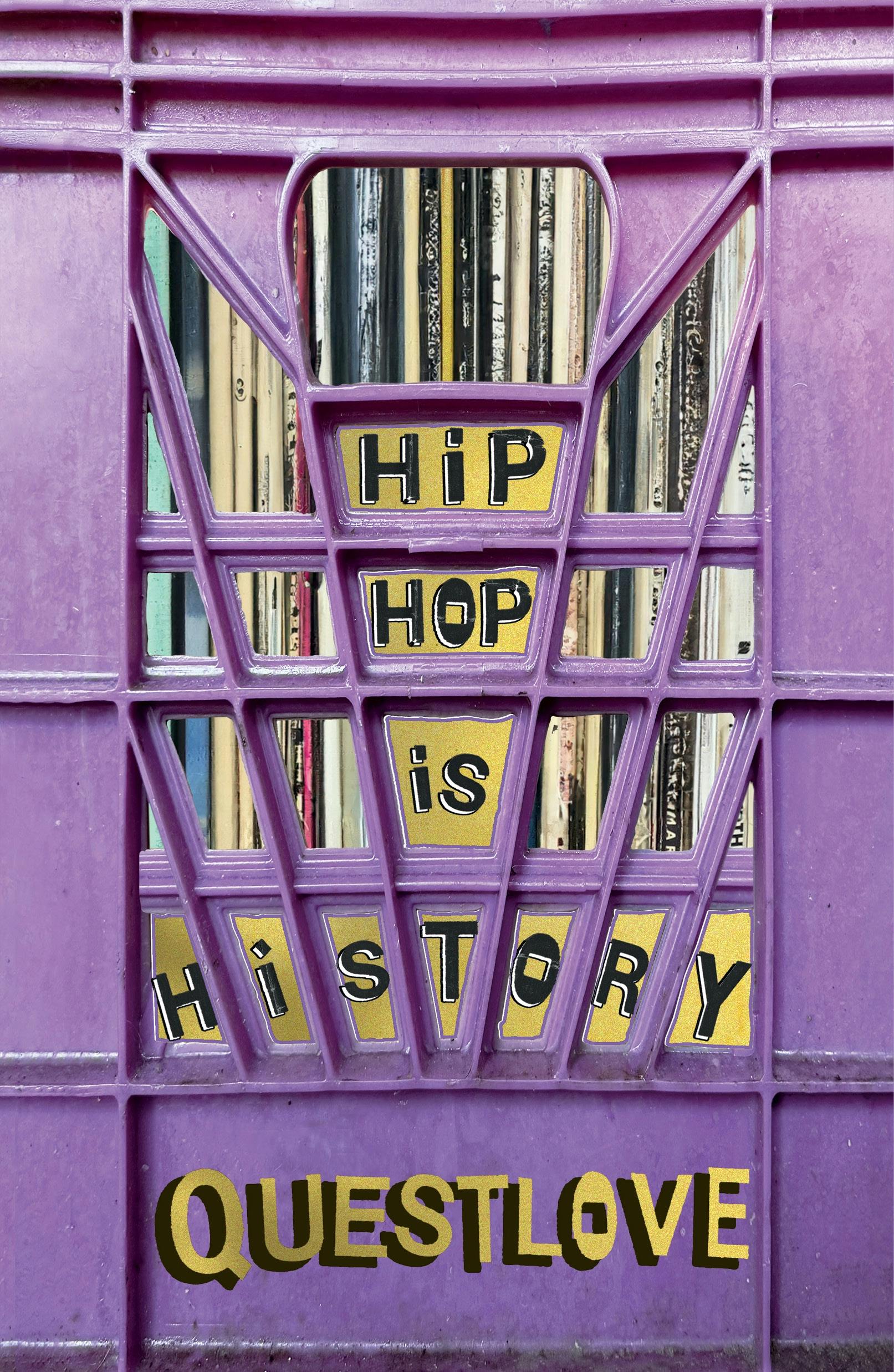

Hip-Hop Is History is Questlove’s attempt to chronicle where hip-hop went—maybe not every place, but surely most of them. It’s a very personal, very loquacious history—written with Ben Greenman, a longtime collaborator on Questlove’s other books—that is as much a catalog of Questlove’s taste in music as it is a record of what actually happened in the genre since 1973 (or, given his quibbles, even before).

Of course, because of the subject matter and the author, the personal elements are as much a feature of the book as anything else. We get an insider’s take on hip-hop’s history, a story of its past, present, and future from one of its leading, lifelong practitioners. But for Questlove, it’s not just about his own journey. As he explains, there’s a number of “invisible words” in the title, starting with “Hip-Hop Is (Revisionist) History.” “What I mean by that,” he writes, “is the entire life span of this young, vibrant genre has been marked by assessments and reassessments, declarations that proved to be untrue in a year’s time, or ten, and opinions that are cracked open like eggs to reveal newer opinions inside them.” To make his point clearer, we then get a set of other possible titles: “Hip-Hop Is (Recurring) History,” “Hip-Hop Is (Two) Histories,” and “Hip-Hop Is (My) History,” each with its own refractive meaning.

To tell these multiple stories, Hip-Hop Is History is divided into 10 chronological sections, along with an introduction, an epilogue, and an extensive concluding playlist, “Hip-Hop Songs I Actually Listen To.” Each section is titled after a famous lyric from the era and is introduced by a page or two of setup before Questlove dives into his meticulously detailed memories. To wit: We get snatches of his childhood in Philadelphia, doing dishes with his sister and hearing the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” for the first time: “The effect was instant. It was as if we had been plugged into an intergalactic power source.”

Obviously, this is one of the pivotal moments in Questlove’s career as a musician, the thing that got him started down the path to everything that came later. (The second thing: meeting Tariq Trotter, better known as the rapper Black Thought, with whom he cofounded the Roots.) But the real insight comes later, when Questlove compares the Sugarhill Gang to Michael Jackson. “Michael had abilities that were not easily transferred to children sitting at home by the radio,” he writes. And then, later, he notes how the group “had a brilliance all its own, but all it required to replicate was a good memory and a night of dedication. I had those. That led to something more complicated and intimate, which was a true shift in identity. I discovered that rap and hip-hop made me popular, but also that I responded to it. It was like a battery snapped into a toy.”