Most associate the Manhattan Project with Oppenheimer, with Hiroshima, and with mushroom clouds over red deserts, but the program’s remit was more open-ended than the development of the bomb itself. One arm of Project research was studies on the effects of radioactivity on human bodies. This field proved a good career move for ambitious scientists looking to climb the ladder into lucrative positions and prestigious academic postings in chemistry and physics departments. A growing understanding of the lethality of airborne radiation inevitably raised the question: How can this be used as a weapon?

As the decades of the criminal malpractice involved in the Tuskegee syphilis experiments dragged on, the U.S. government continued to treat citizens as guinea pigs: the Cold War era saw scientific trials that involved injecting unwitting U.S. citizens with plutonium, and dousing San Francisco (and many other places) with test sprays of bacterial bioweapons. In 1952, the first open-air atomic fallout studies began in Minneapolis, just as construction was getting underway on Pruitt-Igoe. “Army researchers,” Martino-Taylor writes, “would release and then measure ‘cloud travel’ of the material and engage in ‘penetration studies’ inside residences and buildings such as the aging brick structure that was Clinton Elementary School in Minneapolis.”

It was the job of the Atomic Energy Commission to design and field test radiological weapons. “The first step,” wrote one R.B. Snapp in a 1948 Atomic Energy Commission memo, “should be contamination of moderately large areas with graded doses of selected materials,” whereby “materials can be delivered on the ground or as aerosol clouds in which case they would be effective when inhaled.”

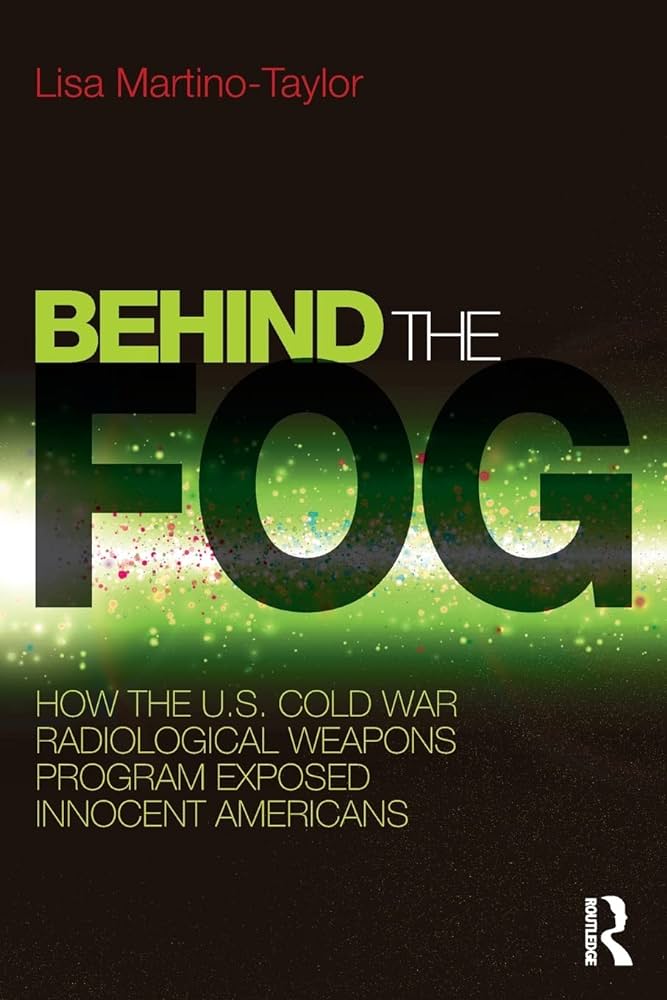

The lies began immediately: brazen contamination of Minnesotans required a fanciful cover story. Minneapolis neighborhoods were canvassed by Army Chemical Corps representatives, who knocked on doors to inform the citizenry that the government was at work inventing a gigantic, billowing, city-sized cloud: a new defense strategy, they said, which would hide the city from Russian bombers, sparing it from nuclear attack. Billowing plumes of harmless fog would conceal important industrial sites.

When sprayer trucks prowled the neighborhoods casting out rolling tufts of soft, gray vapors, the people of Minneapolis, it was hoped, would feel a sense of security at the ingenious precautions of their benevolent government. In reality, the Army Chemical Corps was releasing a cadmium-zinc mixture into the air in order to measure how an atomic blast would disperse radioactive contaminants in an urban area.