If Greenberg and Arsenault tell stories that are almost identical, they employ very different frames of reference. Greenberg advances no specific argument about Lewis and the civil rights movement, but his angle is implicit in the book’s structure. Part One is titled “Protest”; Part Two is “Politics.” John Lewis followed Bayard Rustin’s famous directive, proposed after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, that the movement must transition from protest to politics. Greenberg breaks his book down that way as well.

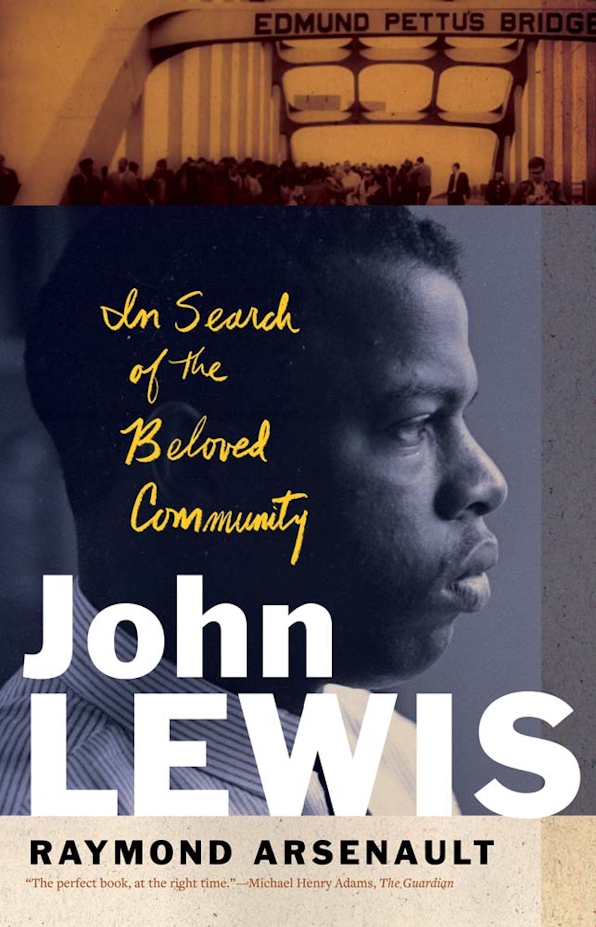

Arsenault, of the University of South Florida, makes a more explicit argument. He centers his book around the concept of the “Beloved Community,” which was Lewis’s “chosen social and moral ideal.” For Lewis, as for Martin Luther King Jr.—who also made frequent use of the term—the Beloved Community operated as both “a philosophical theory and a call to service.” It was “a vision of love, peace, and unity” that stood as an aspiration to “oppressed people and their champions.” It applied to Gandhi’s India and to the American South. The goal was a land where love, peace, justice and democracy reigned, although both Lewis and King understood how difficult it would be to achieve. For Arsenault, it was Lewis’s quest for the Beloved Community that guided his six decades in public life. This goal helped Lewis remain undaunted in the face of terrifying violence. It allowed him to treat his tormentors with love and forgiveness, instilling in him qualities which could strike an outsider as almost superhuman. “If there was one element that set him apart from his peers,” Arsenault writes, “it was his incomparably strong sense of mission.”

While Arsenault provides a guiding principle to help anchor Lewis’s life and career, Greenberg offers absorbing accounts of many crucial events while presenting fuller portraits of other key individuals. The strength of Greenberg’s book is not its argument or analysis, but the way Greenberg provides revelatory details while recounting epic events. Many of these gems come from the author’s own interviews, with hundreds of activists and politicians.

For example, Greenberg gives a riveting portrait of the 1986 congressional contest between Lewis and Bond. The two men had a friendship that went back to their days in SNCC, and their families had remained close. The bruising campaign would fray that friendship. Lewis and Bond were a study in contrasts. Bond was debonair and charismatic. Lewis could come off as rumpled, and speaking in public he sometimes struggled to overcome a speech impediment—to say nothing of his rural Alabama accent. Lewis drove a Chevrolet, Greenberg reports, “when he drove at all.” Bond drove a Peugeot. At the beginning of the campaign, nobody gave Lewis a chance.