In 1958, a year after it achieved independence from colonial rule, Ghana hosted a conference of African leaders, the first such gathering to ever take place on the continent. At the invitation of Ghana’s newly elected prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah, more than 300 leaders from 28 territories across Africa attended, including Patrice Lumumba of the still-Belgian Congo and Frantz Fanon, who was then living in still-French Algeria. It was a time of unlimited potential for a group of people determined to chart a new course for their homelands. But the host wanted his guests not to forget the dangers ahead of them. “Do not let us also forget that colonialism and imperialism may come to us yet in a different guise—not necessarily from Europe.”

In fact, the agents Nkrumah feared were already present. Not long after the event began, Ghanaian police arrested a journalist who had been hiding in one of the conference rooms while apparently trying to record a closed breakout session. As it was later discovered, the journalist actually worked for a CIA front organization, one of many represented at the event.

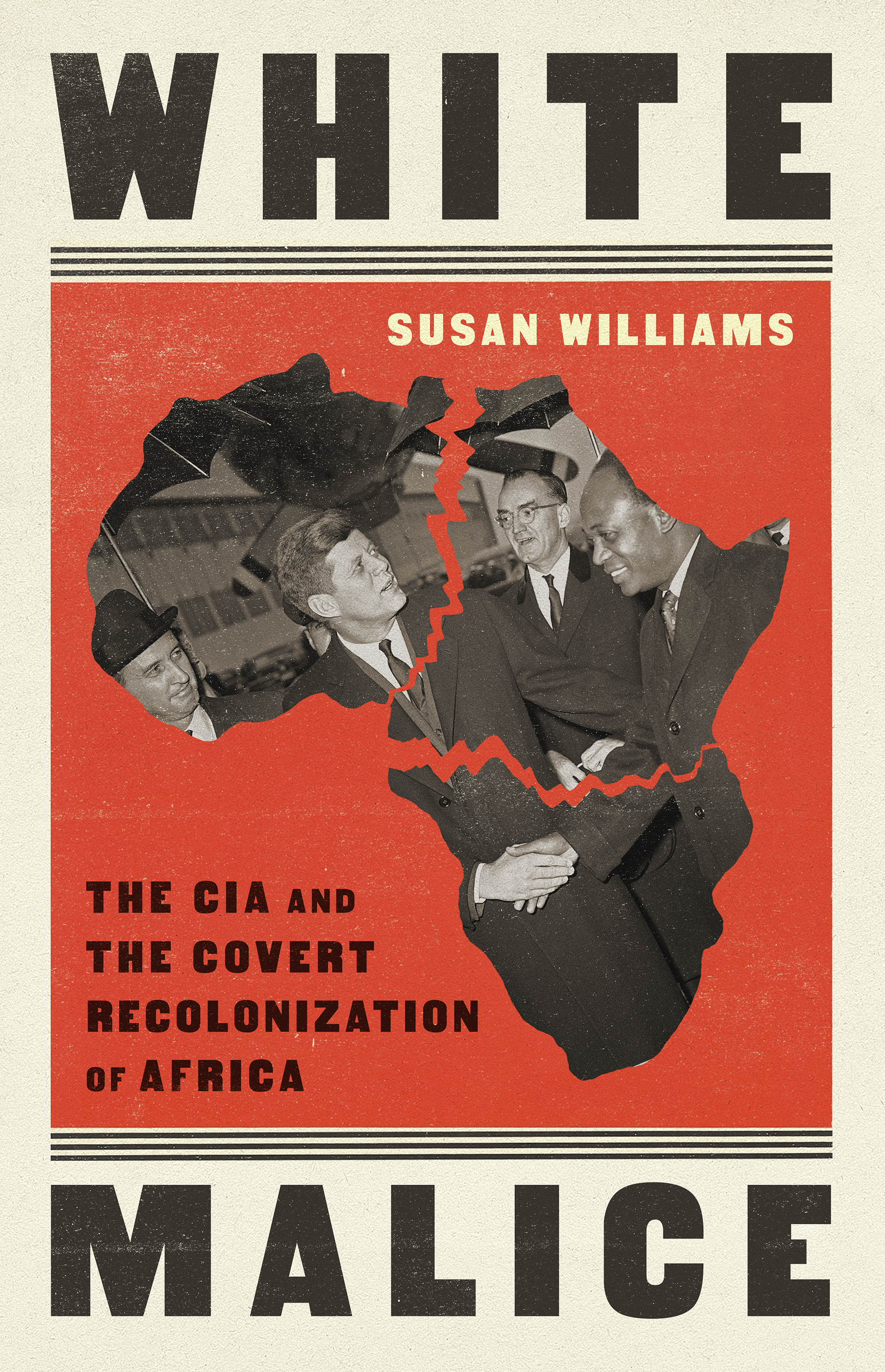

British scholar Susan Williams has spent years documenting these and other instances of the United States’ secret operations during the early years of African independence. The resulting book, White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa, may be the most thorough investigation to date of CIA involvement in Africa in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Over more than 500 pages, Williams counters the lies, deceptions, and pleas of innocence perpetuated by the CIA and other US agencies to reveal a government that never let its failure to grasp the motivations of Africa’s leaders stop it from intervening, often violently, to undermine or overthrow them.

Though a few other African countries appear on the sidelines, White Malice overwhelmingly concerns just two that preoccupied the CIA during this period: Ghana and what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ghana’s appeal to the agency was based merely on its place in history. As the first African nation to gain independence, in 1957, and the homeland of Nrukmah—by far the most widely respected advocate of African self-determination of the day—the nation was inevitably a source of intrigue. The Congo stepped out of its colonial shackles soon after, in 1960. Because of its size, position near southern Africa’s bastions of white rule, and reserves of high-quality uranium at the Shinkolobwe mine in Katanga province, the country soon became the next locus of the agency’s attention—and interference—in Africa.