As bodies of all genders and races move through school hallways today, it may seem counter-intuitive to think of schools as white, female-coded spaces, but they are – on purpose. For much of the colonial era and the early 1800s, the structure for educating the nascent country’s sons was less a system and more an ad hoc collection of male tutors working in schools and private homes. As the population expanded, especially in the northeast, state education leaders took charge of turning the disparate structure into a cohesive institution. To support a viable system, though, they needed more teachers.

In her study of rhetoric and gendered space in the nineteenth century, Jessica Enoch details the language used to describe school-buildings; they were “unclean,” “unsanitary,” and “unsafe.” Floors were debris-strewn and walls were adorned with graffiti, often graphic. Boys’ bodies were broken down through corporal punishment when they failed to please. Reformers, and teachers themselves, spoke of schools in unflattering terms: “We see many a school-house which looks more like a gloomy, dilapidated prison, designed for the detention and punishment of some desperate culprit.”

In effect, school was an unkempt place where schoolmasters turned boys into men, making it a place that was explicitly coded as masculine and, therefore, off limits to women. A necessary step in expanding the teaching force beyond just white men was to make school a place a woman could enter without risking her reputation.

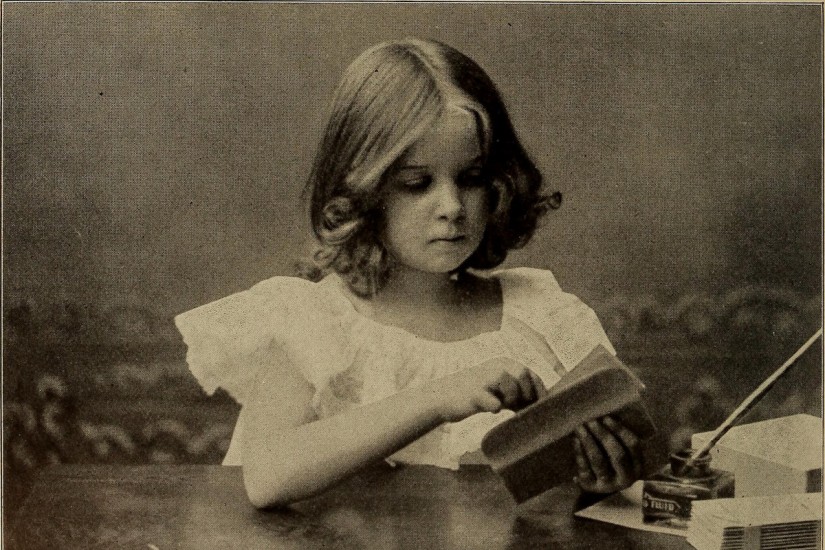

Focusing on white children of all genders, reformers such as Horace Mann and Catharine Beecher saw a shared school experience as something that could unite the country with a common set of values. When they visited schools, they saw messy, chaotic, and dirty. What they wanted was clean, calm, and fresh. What they had were prisons. What they wanted was something like home.