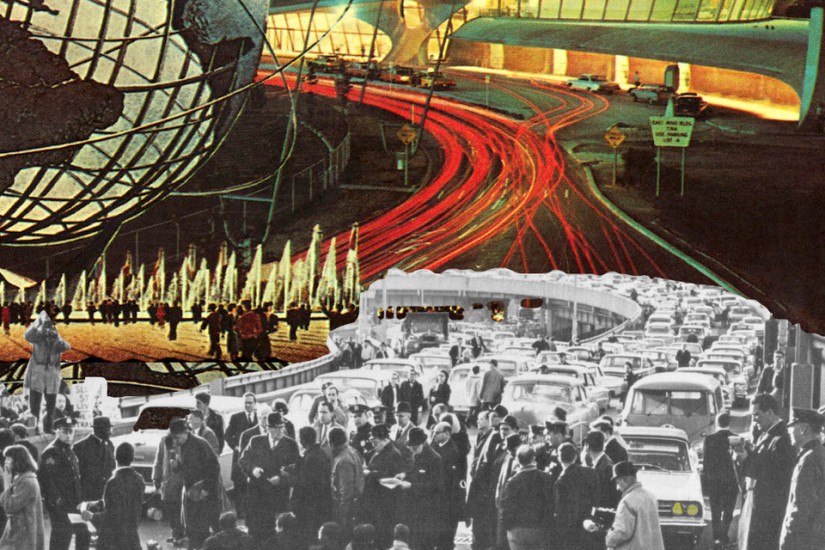

It was supposed to be perfect: a paean to free enterprise, technology, and the progress of freedom made tangible in the form of consumer convenience. Built on the refuse of the Corona dump—F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “valley of ashes”—the 1964 New York World’s Fair would be, “master builder” Robert Moses hoped, “an Olympics of progress and healthy rivalry, a vast Colosseum dedicated to new friendships… the hopes and aspirations of a new world.”

But with less than a month to go before opening day, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announced plans for a fair exhibit of their own: hundreds, if not thousands, of stalled cars on the highways leading to the fairgrounds, tying up traffic for hours and preventing hundreds of thousands of eager fair patrons from entering the gates. Isiah Brunson, the soft-spoken 22-year-old and chairman of Brooklyn CORE, explained it this way:

"We are having the stall-in to shut off traffic at the World’s Fair because the city and the state have seen fit to spend millions and millions of dollars to build the World’s Fair, but have not seen fit to eliminate the problems of Negroes and Puerto Ricans in New York City."

Unless the city of New York made rapid progress on long-standing demands for quality, integrated schools, non-discrimination in housing and employment, and a civilian review board to oversee cases of police brutality in black neighborhoods, CORE would choke off the arterial highways connecting the city to the Fair—and thus, the city to much anticipated tourist dollars.

The local and national press pounced on the story, devoting column inch after column inch, day after day, to the proposed protest—making the stall-in one of the best publicized protests never to occur. Commentators were quick to condemn the protests as unreasonable, dangerous, and even violent; angry letters to the editor poured in. Politicians were not far behind in their condemnations. Senators Hubert Humphrey and Thomas Kuchel warned in a joint statement that “illegal disturbances, demonstrations which lead to violence or to injury, strike grievous blows at the cause of decent civil rights legislation.” Richard Wagner, then Mayor of New York, likened the protests to a “gun held to the heart of the city,” which threatened more harm than “anything that Dixiecrat Senators can do in Washington, or that the forces of bigotry can do in this city.”