For more than a half-century, the standard account of 1876 and its aftermath has been that the election was resolved with a political compromise in which Democrats traded away the presidency in exchange for the end of Reconstruction in the South. That election, which featured Republican Rutherford B. Hayes against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, was one of the closest in American history. Immediately following the election, it was clear Tilden was in the driver’s seat, having captured 184 of the 185 electoral votes needed to win.

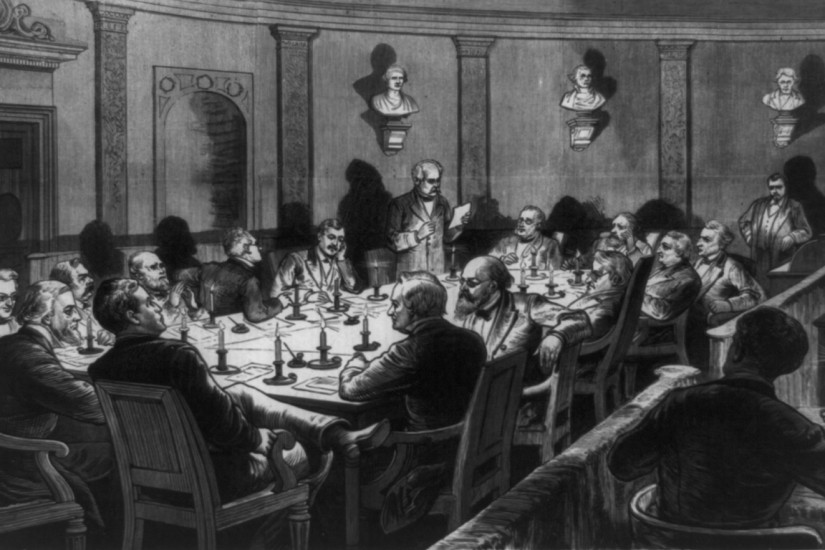

But, contested results in three Southern states threw the outcome into question. When each state subsequently sent two sets of electoral returns to Congress, a constitutional crisis emerged. To solve the dispute, Congress created an unprecedented 15-man electoral commission made up of five members of the House, five members of the Senate and five Supreme Court justices. Representatives from Congress were split evenly between Republicans and Democrats but Republicans had a three-two majority of the justices, and in February 1877 that commission awarded the election to Hayes on an 8-7 partisan vote.

According to this story, which has been repeatedly told and retold in popular news outlets over the past year, once the commission decided in favor of Hayes, bitter Southern Democrats in Congress refused to accept the outcome, threatening to use parliamentary delays to stop Hayes from taking office. To prevent such a cataclysm, congressional Republicans and Democrats supposedly brokered a compromise behind closed doors with Democrats agreeing to accept the commission’s decision in return for, among other things, a promise from Republicans that Hayes would remove the remaining federal troops from the South. Without the presence of federal authorities to stop former Confederates from using violence and racial terrorism to prevent Black Americans from voting, Southern Democrats could recapture control of state governments and restore home rule to White Southerners.

Republicans thus ostensibly sacrificed the fate of Black Americans for the promise of political power. Ten years later, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act of 1887 to address some of the legal loopholes that had led to the election crisis of 1876 and the Compromise of 1877.

The problem with this story? There was no Compromise of 1877.

The argument that a brokered compromise between Republican and Democratic congressmen ended Reconstruction was initially suggested in 1951 by historian C. Vann Woodward. An easy story to tell, Woodward’s thesis was appealing and immediately gained traction, becoming a staple of high school and college history textbooks to this day. It provided a tidy end to the periodization of Reconstruction and a traditional narrative emphasizing the failures and disappointment of the era.