On Sunday, the Senate failed to cut off debate on a proposed coronavirus stimulus package, reportedly because of Democrats’ insistence on stronger worker protections and their refusal to give the Trump administration carte blanche in disbursing hundreds of billions of dollars to affected businesses. Although negotiators seemed close to a deal late Sunday, the partisan wrangling is a reminder that as Congress races to pass a relief package to help suffering Americans and prevent a calamitous recession, the questions it faces are not new. Who, in the face of such contagious misfortune, should get relief and on what basis?

This is not the first time the United States has faced these questions. To most of us, the financial crisis of 2008 is the closest analogy — the moment when the government bailed out big banks, insurers and car manufacturers in an effort to stop the economy’s free fall, explaining that these companies were “too big to fail” or that the economic suffering would be too great, while providing inadequate help with foreclosures and evictions. But such interventions in fact have a much longer history — a history that shows that while disasters have long been spurs to government spending, that spending has often been directed to the already well-off.

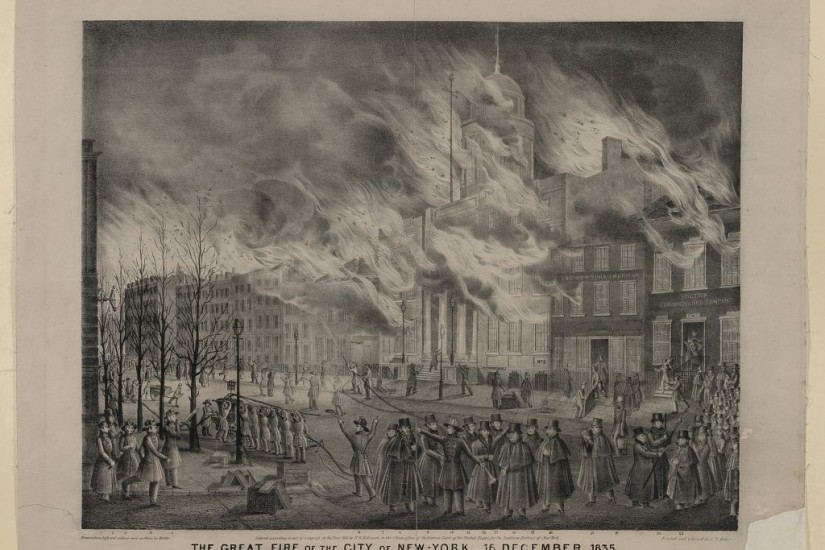

On Dec. 16, 1835, a massive fire destroyed 20 blocks in Manhattan’s commercial district, located on the island’s southern tip (including much of Wall Street). The blaze tore through warehouses full of cotton and other flammable goods, and losses were estimated at $20 million — at a time when the federal government’s entire annual revenue was usually around $30 million. (This amounted to 1.5 percent of GDP. By comparison, the losses associated with 2005’s Hurricane Katrina totaled about 1 percent of GDP.)

Immediately following the fire, New York’s wealthy merchants and local officials sprang into action — action that, then as now, focused largely on securing financial relief from Washington. Less than 24 hours after the fire broke out, New York’s customs collector wrote to the treasury secretary, asking permission to suspend collection on overdue importers’ bonds (essentially IOUs promising to pay duties on imported goods). Two days later, a meeting convened by the mayor voted to form a committee of prominent New Yorkers, including two former U.S. treasury secretaries, to “make application to Congress for relief by an extension of credit for debts due the United States, and a return or remission of duties on goods destroyed.”

On Christmas Eve, the mayor sent off a memorial to Congress spelling out the city’s relief requests. A multi-person delegation headed for Washington, where they stayed at a hotel that housed several members of Congress, met with influential government officers and hosted lavish dinners of duck and champagne. As public meetings in cities like Boston and Baltimore urged Congress to relieve New York’s merchants, rumors spread that the gatherings were the result of an orchestrated effort to encourage other cities to apply public pressure in support of the New York sufferers.

New York City’s merchants could garner such support because they were no ordinary relief-seekers. The federal government depended on them for nearly half its annual revenue, which came in the form of import duties collected at New York port. But it wasn’t the threat to federal coffers that the merchants stressed, so much as the threat to ordinary people: the shopkeepers and farmers in places like Indianapolis and Lexington, Ky. who depended on New York credit to run their stores and farms. Now that the fire had wiped out nearly all of New York’s insurance companies, the merchants warned, they might be forced to call in those loans. Without relief from the federal government, they predicted, their loss would become the country’s loss; their hardships would be borne by voters in the East, the South and the West. No one would be spared.

Then as now, debates were shaped by the idea of contagion. Three years earlier, New York City had been hit hard by a cholera outbreak. Just like cholera spreading through a densely packed city, or a fire in a crowded port, a credit crunch in the nation’s financial center could easily harm small-town merchants in the nation’s remotest regions. New Yorkers stressed this argument repeatedly, and members of Congress proved receptive.

As in 2008, not everyone in Congress was eager to grant the merchants’ request. Relief would not go to the “poor mechanic, the widow, the orphan,” argued Kentucky’s Benjamin Hardin, but instead to the richest residents of the nation’s richest city. And what was Congress supposed to do the next time a fire sufferer sought relief? If Congress granted these merchants’ request, Rhode Island’s Dutee Pearce pointed out, they would have a hard time saying no to future fire victims.

Besides, why weren’t these businessmen insured? Bailing them out would just discourage them from purchasing insurance in the future, predicted Massachusetts’ Edward Everett. Even more concerning, argued Kentucky’s William Graves, was that the nation was already too dependent on these merchants for its financial well-being; propping them up would just compound the problem.

But other House members said these were necessary evils. Aid to New York’s importing merchants would ultimately trickle down to city laborers, Massachusetts’ Stephen Phillips assured, because it was on these merchants that laborers depended for credit and employment.

Ultimately, arguments like these prevailed. Congress granted the merchants’ requests, remitting duties paid on destroyed goods and granting a multiyear, interest-free credit extension on back taxes — but only to those New York merchants who could show they had lost property totaling at least $1,000, on the logic that it was these rich merchants whose failure would especially threaten the national economy. They granted relief, they explained, for the same reason Congress responds to disaster with bailing out large businesses today: because to do otherwise would, in the words of future president James Buchanan, risk “such ruin … as would be felt to the very extremities of the Union.” As goes New York, so goes the nation.

The actions and reasoning of Congress in the wake of New York’s 1835 fire set a precedent that remains with us today. In 2008, when Congress pumped cash into big banks, it did so to avoid an even deeper recession. While most scholars think the program succeeded in this goal, critics contend that the relief rewarded risky behavior and disproportionately benefited those already at the top of the economic ladder.

As the debates following the 1835 fire show us, such criticisms have a long history. From merchant relief in 1836 to bailouts in 2008, measures taken to stem crises have gone almost exclusively to the wealthiest interests, worsening existing disparities in the name of necessity.

But disaster can also be opportunity. Just as the Great Depression created the political conditions that made the New Deal possible, the current crisis presents a chance to make fundamental, lasting enhancements to the social safety net — enhancements that would both help the economy and ease the burdens of struggling Americans now and for the long-term.

While one-time cash payments to those making under $99,000 is a step in the right direction, more permanent moves would be even better. Giving billions to the airlines, no strings attached, might help to keep a critical industry afloat. But spending money to improve the economic security of all Americans will do far more to keep our entire society afloat: one thing we can all agree is too big to fail.